Story highlights

Hot air will drive turbines to create electricity, then flow out through a tall chimney

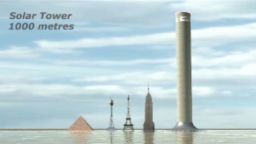

The tower will be the second tallest structure in the world

EnviroMission, an Australian company, wants to build it in the Arizona desert

You don’t have to be a science major to know that heat rises: Just step into an attic on a hot summer day. But what you might not know is that this basic scientific reality could also help create clean energy for entire cities.

For centuries, architects have taken advantage of rising heat to help cool some structures. Solar chimneys allow the rising air to go out of the building, taking the heat with it.

Today, Australian entrepreneur Roger Davey wants to take advantage of that phenomenon – with a twist.

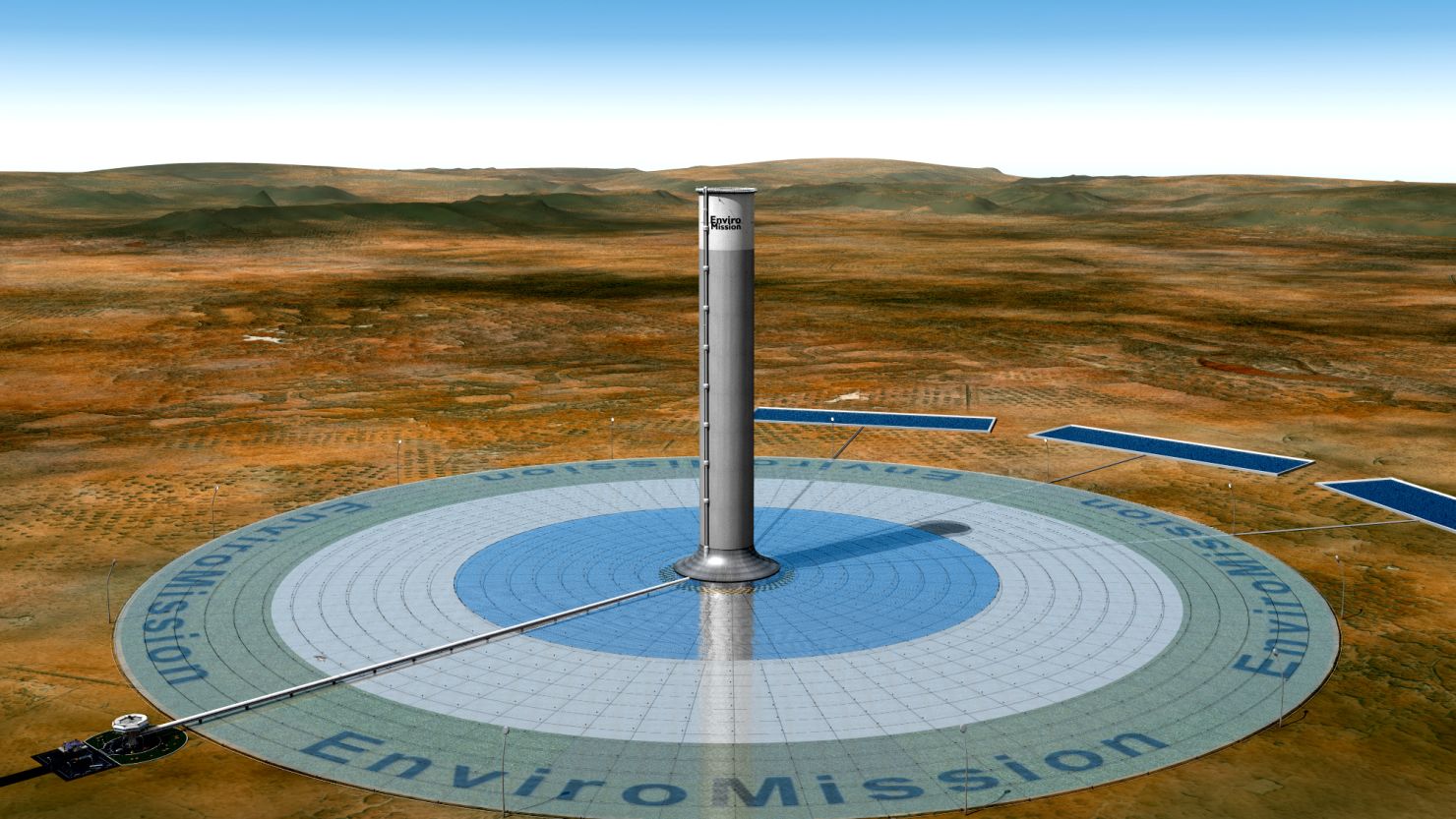

He wants to create, capture and control hot air to help power cities. He plans to build a huge solar updraft tower, 2,600 feet tall, in the Arizona desert. As the hot air moves into the tower, it would turn 32 turbines, spinning them fast enough to create mechanical energy, which generators convert to electricity.

His company, EnviroMission, says such a tower can create up to 200 megawatts of power, enough to power 100,000 homes. He says they don’t intend to put coal or nuclear or alternative power out of business, but want to be a strong, no-carbon emission supplementary source.

“One of the most important things I think that differentiates this from anything else is its ability to produce power as and when required,” said Davey, chief executive and executive director of EnviroMission, the company behind the solar updraft tower.

That sets it apart from solar (not available at night) and wind energy (not available on a calm day), which he referred to as “spasmodic.”

He also touted its ability to produce power without the use of water to generate electricity. Coal-fired and nuclear plants use massive quantities of water, and solar panels need to be washed frequently to keep them working well.

On the drawing board

The EnviroMission tower is only a concept right now, but Davey says the technology has been proved by a different company’s smaller version that worked for seven years on the plains of Spain. It created 50 kilowatts of electricity, according to that company, the German builders Schlaich, Bergermann and Partner.

But the 125-ton iron structure toppled in 1989 after its support cables broke in a lengthy storm, a spokeswoman for Schalich, Bergermann and Partner, said in an e-mail. The tower had already collected all the data to prove it could work, she added.

A small tower began operation in China last year, according to the Xinhua news agency. The Chinese company’s project reportedly will cost $208 million and will be built in phases. The first section of the plant produces 200 kilowatts per day, Xinhua reported.

EnviroMission is the only publicly traded developer working on this technology, a company spokeswoman said.

Its model calls for a tower with no support wires and, unlike the other structures, it will be built from cement. The solar tower would be the second-tallest structure in the world, slightly shorter than Dubai’s Burj Khalifa skyscraper.

EnviroMission says its tower will stand for 80 years, far longer than the average life for a field of solar panels, which some would see as an alternative with a smaller upfront cost.

Davey says the Arizona project will cost $750 million to build at its present size and scope (with further refinements the price could rise or fall 10% to 15%, he says).

EnviroMission has already raised “substantial capital” for its project, according to spokeswoman Kim Forte.

The company also recently presold the power that would be created at one of the Arizona facilities to the Southern California Public Power Authority, which comprises 12 utilities.

Mohammad Taslim, a professor of mechanical engineering at Northeastern University, says the two important concerns are: Will the plant produce as much energy as EnviroMission predicts and will it be economical and environmentally friendly?

“Fundamentally from an engineering standpoint it is sound,” he said. “I believe that the question is not that this will not work at all. It might be the claim of 200 megawatts is not quite reachable at the peak.”

Taslim initially said he thought the engineers should consider composite materials like carbon fiber. But, after a few back-of-the-envelope calculations, he concluded, “an 800-meter structure of composite materials cannot withstand its own weight and a much more complicated structure is required.”

According to EnviroMission, the amount of carbon pollution created by the manufacture and shipment of the cement and other materials needed to build the facility will be offset after 2? years of operation.

Spinning turbines create electricity

The technology works like this: Unlike normal solar photovoltaic panels that convert the sun’s light into energy, the EnviroMission tower would create solar-thermal power, from both the sun and the wind.

Like a greenhouse, the sun heats up the air underneath a huge translucent, sloping canopy around the tower that is about as wide as a football field.

The air is heated to about 194 degrees Fahrenheit (90 degrees Celsius) and then it flows into the tower, spins the turbines and rises.

The higher the tower, the stronger the flow of air. The faster the turbines spin, the more electricity possible.

After sundown, the ground continues to release heat and more electricity would be generated.

The long road ahead

Davey says the hurdles to getting his solar tower built are a combination of political factors, environmental policies and the cheap cost of fossil fuels. He wanted to build this project in his home country of Australia, but he says the United States has a more acceptable political climate.

He also said that for the past 10 years EnviroMission has been doing its “due diligence” in designing a better solar tower plant to assure its potential private investors.

“We had to improve the technology from what it was from when the plant in Spain was built to what it is now – commercially viable,” he said.

The plant should take about two years to build and provide up to 1,500 construction jobs, he says. Then once the site is operating, a 30-person staff will operate the plant, providing maintenance to the canopy and turbines, as well as security and possible tours. Because air is free, operating costs will be minimal, he said.

The next step is determining the final capital costs, which will take a few months.

“And then you can work out whether the economics stack up,” he said. “We’ve got to go to the bankers and ensure you can get it banked. We believe it will.”