Story highlights

Tintin as much an explorer and amateur archaeologist as a reporter

'Tintinologist' Jean-Marc Lofficier lists his favorite archaeology-themed Tintin adventures

Herge interested in anthropology and archaeology, influenced by discoveries of the day

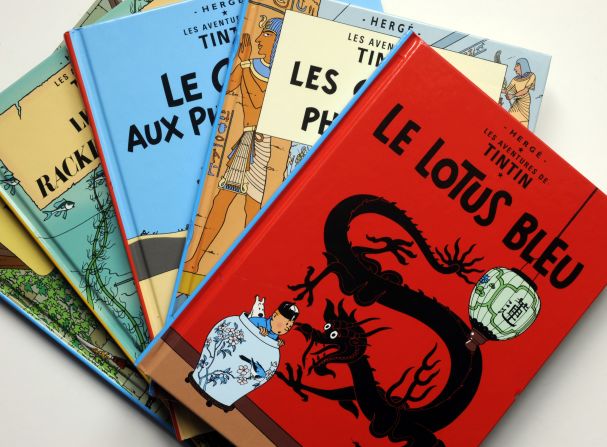

Herge’s famous boy reporter certainly liked to stray from his native Belgium.

Tintin’s official profession may be that of a reporter, but he is just as much an explorer and archaeologist, dashing around the world to chase down ancient artifacts in addition to nefarious villains and a good story.

Carrying on a venerable tradition of filmic archaeologists and adventurists such as Indiana Jones, the new Tintin film by Steven Spielberg, entitled “The Adventures of Tintin: The Secret Of The Unicorn,” mixes the story-lines of several of Herge’s books and follows Tintin and friends hunting for centuries-old treasure.

“Herge was always interested in exotic locations and travel around the world,” said Paris-based ‘Tintinologist’ and comic-book artist Jean-Marc Lofficier.

“Keep in mind that he comes out of the tradition of (French author) Jules Verne, whose characters are always traveling around the world and finding lost civilizations and incredible ruins,” he continued.

Lofficier, who is co-author of the Pocket Essential guide to Tintin, spoke to CNN about his favorite historical escapades and archaeological “MacGuffins” from the classic series of comic books, beloved around the world by adults and children alike.

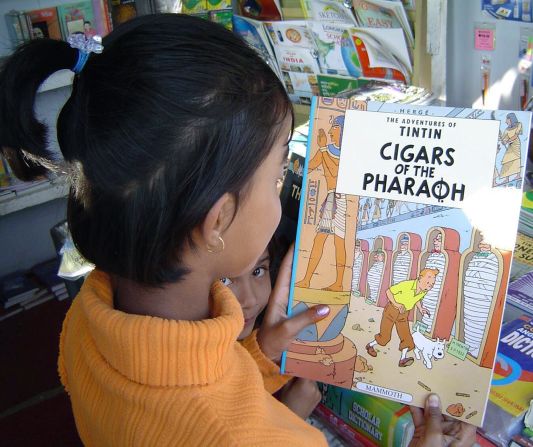

‘The Cigars of the Pharaoh’

Published in 1934, this is the first Tintin adventure to have featured an archaeological premise, Lofficier says, explaining that the storyline was “clearly influenced” by the discovery of the tomb of ancient Egyptian Pharaoh Tutankhamun by Howard Carter in 1922.

The plot begins with Tintin meeting an archaeologist looking for the lost tomb of a mysterious Pharaoh and is driven by the appearance of a number of cigars bearing mysterious – seemingly ancient Egyptian – symbols.

Moving from Egypt to Arabia and on to India, Lofficier says the book is “a catalog of archaeological myths and popular clichés from the late 19th and early 20th centuries.”

‘The Broken Ear’

This book, published in 1937, charts the hunt for a South American idol that is stolen from the Museum of Ethnography in Brussels.

“It’s kind of a fetish object, a small wooden idol with a broken ear,” said Lofficier. “We find out that there is some kind of a precious stone hidden in the idol and everyone is fighting over it.”

“Herge is using the complications of having various people try to seize the idol as a pretext for a travelogue around South America,” says Lofficier, explaining that Herge was as interested in anthropology as he was archaeology, with Tintin coming into contact with native South American tribesmen along the journey.

‘Prisoners of the Sun’

Published in 1949, “Prisoners of the Sun” is a sequel to “The Seven Crystal Balls,” in which a group of explorers are struck down with an unexplained illness after discovering the tomb of a mummified Inca in Peru – a storyline which echoes the supposed Tutankhamun “curse” that was much-discussed at the time.

In “Prisoners of the Sun,” Tintin and friends are charged with rescuing their friend Professor Calculus from native tribesmen, who are angry about what they see as the desecration of their culture and are eventually revealed to be last remaining descendants of the Incas.

“At the end of the day, it is about the right of the Inca civilization to (protect their) culture,” said Lofficier. “Herge presents the other side of the issue, which is that these civilizations deserve to be respected – which considering the time period, is very forward-thinking.”

In the end, Tintin manages to secure the release of the kidnapped explorers and in exchange promises never to reveal the location of the remaining Incas.

‘The Secret of the Unicorn’ and ‘Red Rackham’s Treasure’

Moving from ancient civilizations to pirates and buried treasure, “The Secret of the Unicorn” and “Red Rackham’s Treasure” form the basis for the script of “The Adventures of Tintin: The Secret Of The Unicorn.”

Both chart Tintin and various other parties’ attempts to unearth the lost loot of 17th century pirate, Red Rackham.

“Half of (The Secret of the Unicorn) is actually a flash-back to the great days of the pirates,” said Lofficier, explaining that Tintin’s friend Captain Haddock is the ancestor of the sea captain who killed Rackham all those years ago.

At the end of “Red Rackham’s Treasure,” after a voyage in a submarine resembling a shark, the treasure turns out to be hidden in Haddock’s ancestral home.

‘Flight 714’

“Flight 714 is the penultimate Tintin book and has a very strange ending,” explains Lofficier.

The book, published in 1968, is strongly influenced by the science fiction of the time, said Lofficier, and features an incredible plot device in which the gods worshiped by the ancient peoples of a volcanic island Pulau-Pulau Bompa are revealed to have been extraterrestrials.

“We are left with an ongoing mystery, (presented as) the ultimate answer to archaeology,” said Lofficier.