Story highlights

Landmark exhibition in London brings nine Leonardo da Vinci paintings together

Highlights include newly rediscovered work "Salvator Mundi"

Show features both versions of "The Virgin of the Rocks," shown together for first time

Exhibition described as "once-in-a-lifetime" by National Gallery curator

A “once-in-a-lifetime” exhibition of paintings and drawings by Renaissance master Leonardo da Vinci opened in London Wednesday.

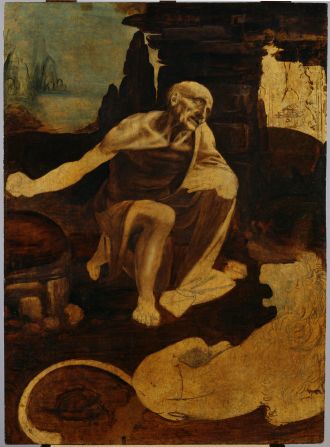

The show, “Leonardo da Vinci: Painter at the Court of Milan,” at London’s National Gallery includes nine of da Vinci’s 15 surviving paintings – the first time so many of the artist’s paintings have been exhibited together. The estimated insurance value of the works on show is $2 billion.

“I think this is maybe a once-in-a-lifetime experience,” said Luke Syson, curator of Italian painting before 1500 for The National Gallery. “(The exhibition) sort of tops everything, it’s a moment in history really.”

Highlights include the recently rediscovered “Salvator Mundi” and the first version of “The Virgin of the Rocks,” which has never before left the Louvre Museum, Paris. It is being exhibited opposite the National Gallery’s recently restored version of “The Virgin of the Rocks.”

The show focuses on the period of da Vinci’s life when he was living and working at the Sforza Court in Milan as a painter and engineer for the Duke.

It was during this time that he produced paintings such as “La Belle Ferronniere,” “The Lady with an Ermine,” his first version of “The Virgin of the Rocks,” “Madonna Litta,” and fresco “The Last Supper.”

All of these works, barring “The Last Supper” (which is painted onto the wall of a church in Milan) are on view at the National Gallery. A copy of “The Last Supper,” painted by da Vinci’s contemporary Giampietrino, is on display.

It was an important period for da Vinci, says Syson, and the exhibition charts his evolution as a painter and thinker.

He developed his concept of painting as a science, where he equated seeing with perceiving – a radical idea in the 15th century.

“(Da Vinci) thought that the eye and what you could see was the most important way of experiencing the world and that painting could encapsulate all that was visible and invisible in it.

“(He’s) getting closer to the belief that a painter in some ways imitates the mind of God himself, (his) own creativity is akin to god’s creation and it’s a huge leap,” he said.

It was also during this period that da Vinci became interested in the sciences and especially anatomy, and the many drawings on display show a furious mind, constantly thinking, sketching and pushing at its intellectual limits.

Also on public view for the very first time as a Leonardo da Vinci painting is the “Salvator Mundi,” displayed alongside preparatory drawings.

According to art historian Richard Stemp, “To suddenly have a new painting by Leonardo when he painted so few in the first place is enormously exciting.”

He added that, despite the painting’s rigorous authentication process, there are still going to be art historians who “will want to go along and see that it’s not by Leonardo.”

To put his work into context, paintings by da Vinci’s associates and pupils, including Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio (originally thought to have been the painter of “Salvator Mundi”) and Giovanni Ambrogio de Predis are also included in the show.

One of the key themes in the exhibition is beauty.

Da Vinci used geometry to refine proportions and adhered to prevalent ideals of beauty in his work, said Syson. The aim was to achieve perfection.

“Leonardo realized that paintings could make you fall in love, and in order to do that you needed to be amazed by a kind of absolutely essential beauty,” he said.

“What he’s showing is a painter that can (not only) record beauty but create beauty above all,” he continued.

Many of the drawings featured in the “Leonardo – The Lost Painting” are held in the Royal Collection: royalcollection.org.uk