Editor’s Note: Loran Nordgren is an assistant professor of management and organizations at the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University.

Story highlights

Three GOP presidential candidates say waterboarding is not a form of torture

So which is it: Illicit torture or an acceptable interrogation practice? asks Loran Nordgren

Nordgren: People who don't experience something can't estimate just how painful it is

People who volunteer to experience waterboarding see it as torture, Nordgren says

Republican presidential candidates Herman Cain and Michele Bachmann said at Saturday’s foreign policy debate that they would renew the use of waterboarding, the controversial practice banned by President Barack Obama. “I don’t see it as torture. I see it as an enhanced interrogation technique,” Cain said. His comments were met with loud cheers of support from the debate audience. Bachmann, meanwhile, called the practice “very effective” and said Obama “is allowing the ACLU to run the CIA.” After the debate, Romney aides told CNN that he does not believe waterboarding is torture.

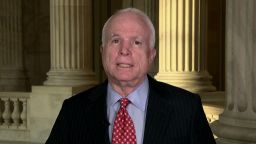

But this issue doesn’t divide neatly along party lines. During the debate candidates Ron Paul and Jon Huntsman outright opposed the practice. “Waterboarding is torture,” Paul said. “It’s really un-American to accept, on principle, that we will torture people that we capture.” The next day both Sen. John McCain and President Obama criticized the pro-waterboarding rhetoric and reaffirmed their opposition to the practice.

The United States has also been historically inconsistent on this issue. Although the use of waterboarding was widespread in the aftermath of 9/11, in the aftermath of World War II the United States not only condemned but prosecuted and convicted a number of Japanese troops and officials for subjecting United States troops to waterboarding.

So which is it: Illicit torture or an acceptable interrogation practice? And how should we decide?

Recently my colleagues Mary-Hunter McDonnell, visiting assistant professor of law at Northwestern, and George Loewenstein, a behavioral economist at Carnegie-Mellon, and I examined the psychology behind how we evaluate enhanced interrogation tactics. Our experiments revealed several insights that can inform the debate on waterboarding and other so-called enhanced interrogation techniques.

Most countries define torture in terms of pain severity. For example, the United Nations Convention Against Torture, of which America is one of many signatories, abjures the use of torture, which it defines as “any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person.” This means that, legally speaking, whether waterboarding is illicit torture or an acceptable interrogation practices depends on the amount pain and suffering waterboarding inflicts.

Because most policymakers have never experienced waterboarding and other enhanced interrogation tactics for themselves (Sen. McCain aside), they must rely on their inexperienced intuitions about how painful these practices seem. This task has become all the more difficult with the advent of enhanced interrogation techniques such as prolonged sleep deprivation, social isolation, and exposure to cold temperatures, which are designed to induce physical and psychological distress without inflicting enduring harm.

Yet over the past 15 years, psychologists have discovered that people who aren’t enduring a painful experience have a hard time estimating just how painful it is. This finding is known as an empathy gap, and it helps to explain why doctors underestimate their patients’ pain and why patients themselves underestimate how painful upcoming procedures will be.

To test the idea that empathy gaps might distort the evaluation of torture policy, we asked people to evaluate common enhanced interrogation tactics like sleep deprivation, solitary confinement, and exposure to cold temperatures.

Some participants (the control group) evaluated these practices under normal conditions, while others (the experimental group) made their judgments while experiencing a mild version of the pain associated with those techniques. These participants submerged their hand in ice water (exposure to cold temperatures), felt social exclusion by being rejected by a group (solitary confinement), and were tested at the end of a three-hour night class (sleep deprivation).

In each case the experimental group estimated the interrogation tactics to be significantly more painful, less ethical, and less acceptable as a practice than participants who made their judgments free of pain, as policymakers normally would. These findings suggest that policymakers (and the concerned public) suffer from a fundamental bias when evaluating waterboarding and other interrogation tactics.

It appears that the legal standard for evaluating torture is psychologically untenable. Policymakers simply cannot appreciate the severity of interrogation practices they themselves have not experienced, a psychological constraint that in effect encourages torture.

Indeed, in several well-publicized incidents, public figures who denied that waterboarding was torture volunteered to experience it themselves, and almost instantly changed their minds. In combination, a range of empirical evidence points to the need for a more restrictive legal standard for evaluating the ethicality of interrogation techniques.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Loran Nordgren.