Story highlights

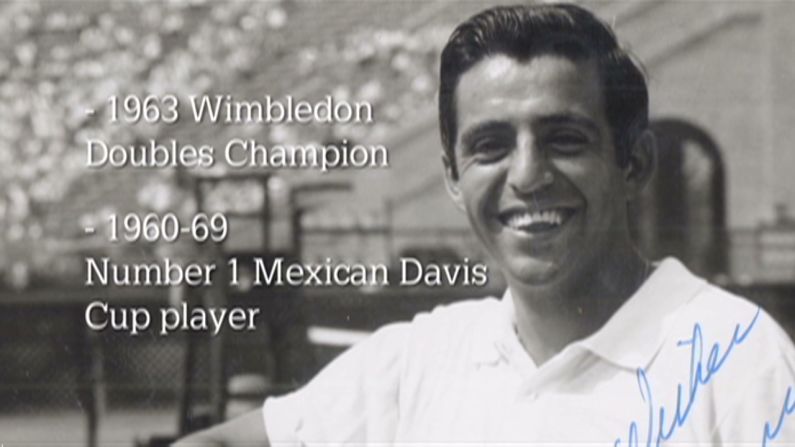

Rafael Osuna is Mexico's greatest ever tennis player

He was tragically killed in an air crash in 1969 aged just 30

Osuna was the first player from Latin America to be World No. 1

He won the U.S. Open in 1963 and three grand slam doubles titles

When Mexican Airways Flight 704 crashed into the mountains near Monterrey on June 4, 1969, it claimed the lives of 79 people including a national hero and one of the greatest players to wield a tennis racket.

He had carried the hopes of his country for a decade until his life was tragically cut short, just days after leading Mexico to an epic victory over all-conquering Australia in a Davis Cup tie, the crowning achievement of a remarkable career.

He was a grand slam winner, a former world number one and one of the most innovative doubles players in the sport’s history.

Rafael Osuna Herrera was, quite possibly, the greatest tennis player you never knew, a compelling and inspirational figure, but more than 40 years since his death he has been largely forgotten.

Perhaps this is because Osuna was at his peak during the 1960s, before the blanket television coverage of grand slams and major competitions such as the Davis Cup.

Clips of him in action are mostly in grainy black and white, but even to the non-expert eye his style of play and breathtaking speed on the court stood out.

His modern namesake Rafael Nadal batters opponents into submission with grueling baseline rallies, but Osuna used his lightning-fast reactions to shorten points, rushing to the net behind his service to pull off unlikely volleyed winners.

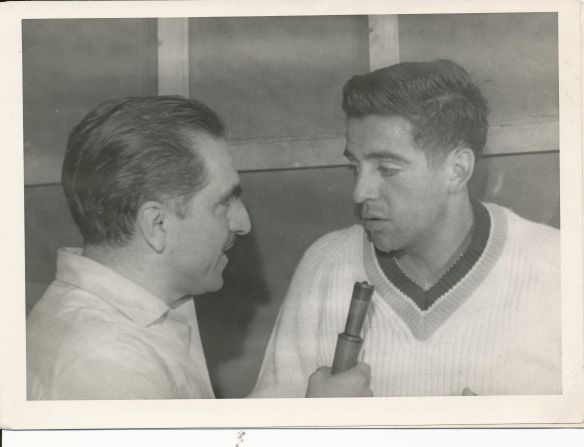

“He was the quickest of his era,” recalled legendary tennis broadcaster Bud Collins, who commentated on many of the Mexican star’s biggest matches, including his 1963 U.S. Open final win over Frank Froehling on the grass of Forest Hills.

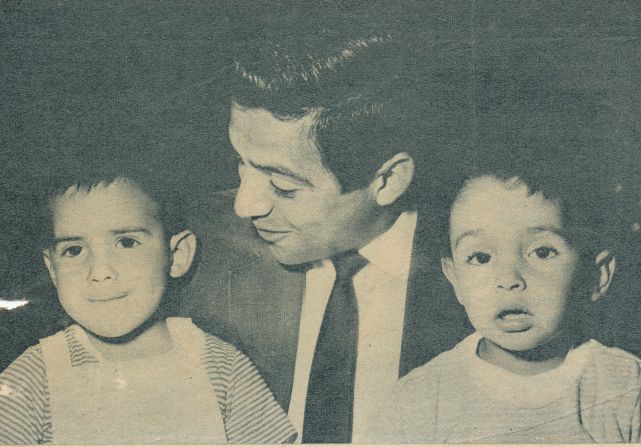

Osuna’s nephew Rafael Belmar said his uncle had developed his quickness about court from his early days as a junior table tennis player, when forced to run around the table to reach the drop shots of canny older opponents.

Belmar also recalled a chance conversation with karate legend Chuck Norris, who he met while studying in the United States.

Norris was telling a story about the only two men he knew who could catch a fly with two fingers. One was the martial arts and film legend Bruce Lee, the other was Belmar’s uncle Rafael.

“I was amazed,” Belmar told CNN. “But in a way not surprised, he could intercept an opponent’s drop shot before it bounced!”

Osuna, who came from a middle-class Mexican family, studied at University of South California (USC), going there as a raw freshman and developing his game under the tutelage of coach George Toley.

“Everything he did on court was bad fundamentally, in part because he was such a natural and could get away with it,” Toley wrote in a book about his experiences at USC.

“We had to tear his game apart, but he could move like a GOD!”

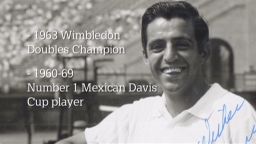

Osuna’s first notable success came at Wimbledon in 1960 when he won the doubles with his USC roommate Dennis Ralston, the first unseeded pair to achieve the feat.

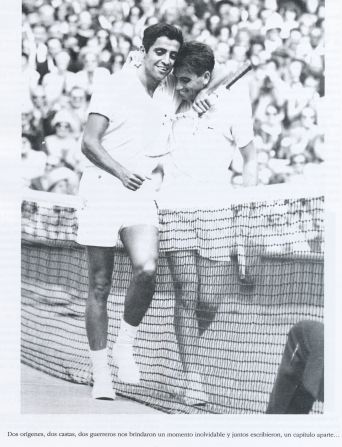

It was the catalyst for an outstanding doubles career, which saw him claim further grand slam titles at the U.S. Open in 1962 and Wimbledon in 1964 with his compatriot and Davis Cup partner Antonio Palafox.

Their doubles combination helped Mexico to the Davis Cup final in 1962, but they were beaten by one of the greatest Australian line-ups of all-time, spearheaded by Rod Laver.

Collins believes that had Osuna maintained his college partnership with Ralston, his success might have been even greater in grand slams, but it was with Palafox that the pair experimented with a new formation that is commonly used today.

When serving, the other player would straddle the center line, keeping hunched down low to avoid being hit, before springing up to intercept their opponent’s return.

It’s called the “I-formation” but Collins said Osuna and Palafox were the first to use it.

Such unconventional tactics were Osuna’s hallmark and played a major part in his only grand slam singles success in 1963.

Froehling was renowned for his big serve-and-volley game. Osuna confounded him by standing way back behind the baseline and then floating back lobbed returns.

An easy 7-5 6-4 6-2 victory followed and a place is tennis history as the first and only grand slam champion from Mexico.

It earned Osuna the International Tennis Federation’s world No. 1 ranking at the end of 1963, the same year he graduated from USC with a degree in business administration.

In the pre-Open era, a professional circuit ran in opposition to the regular tennis calendar, with players like Laver joining the paid ranks after accumulating grand slam titles.

Osuna, however, spurned the opportunity and took a job with the tobacco giant Phillip Morris, while still playing full time.

“He was offered $120,000 in 1962 by Jack Kramer (who ran the pro tour) but turned it down,” claimed Belmar.

“My uncle had houses in Beverly Hills, in Mexico City and the Venezuelan capital of Caracas, so money was clearly never an issue.”

Keeping his amateur status meant Osuna could continue to play at Wimbledon, where with Palafox he won his final grand slam doubles crown and became the first and only Mexican to grace the cover of the official tournament program in 1964.

Osuna reached the semifinals of the U.S. Open the following year, and when the Olympic Games came to Mexico in 1968 he won the exhibition tournament in both singles and doubles.

Tennis did not become an official medal sport until the 1988 Games in Seoul but the Osuna family still hold dear the gold medals he was awarded.

Approaching the end of his career at the top, Osuna continued to play Davis Cup and on the clay in Mexico City summoned up one last giant effort as 17-time winners Australia visited for a zonal final.

Osuna won all three points for Mexico in a 3-2 victory, including a crucial singles win over Australian No. 1 Bill Bowery, again deploying unusual tactics in the fourth set to prevent his opponent from volleying before breaking his service for the final time.

No-one can know if Mexico might have progressed further – the team lost in the next round to Brazil after Osuna had lost his life in one of his country’s worse airline disasters.

Since his death, Osuna has been honored, with a statue erected and a tennis stadium in Mexico named after him.

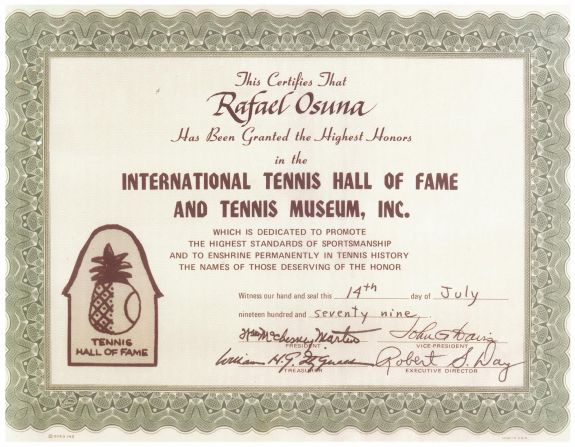

The ultimate accolade came in 1979 when he was inducted into the Tennis Hall of Fame, but in recent years, with Mexicans struggling to make an impression on the courts of the world, his place in the national consciousness has waned.

“Maybe Mexico is not so good at celebrating our heroes, he has become an obscure figure from the past,” Belmar said.

Belmar tried to follow in his uncle’s footsteps, playing collegiate tennis, while others such as top 10-ranked Raul Ramirez were also inspired by his achievements.

Spanish player Manuel Santana, the 1966 men’s Wimbledon champion, perhaps best sums it up: “The man surpasses his achievements.”