Story highlights

Breast implants made by French company PIP found to contain industrial-grade silicone

Some 300,000 women in 65 countries received implants made by the company

Health authorities in France have offered to pay for women to have them removed, replaced

PIP founder Jean-Claude Mas charged with involuntary injury

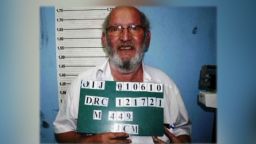

The founder of a French company that made breast implants linked to a major health scare has been charged by police investigating the scandal.

Jean-Claude Mas, former boss of Poly Implant Protheses (PIP), faces charges of involuntary injury over the now-defunct firm’s use of substandard ingredients in its implants.

So what is wrong with the implants? What are the risks? And what is being done to help those affected by the scandal?

What is the problem?

Implants made by France’s Poly Implant Protheses (PIP) were banned in 2010, after it was discovered that they contained industrial-grade, which has more contaminants than the medical-grade gel they should have used.

Mas is reported to have admitted authorizing the use of two gel formulas at PIP: A high-end version for wealthier clients, using American-made medical silicone, and a “house” formula for everyone else. This was made from cheap industrial silicone, meant for use in mattresses, allegedly in order to cut costs and boost profits.

In December 2011, authorities in France sparked a worldwide alert when they advised 30,000 French women who had been fitted with the potentially defective implants to have them removed.

The implants are believed to have a higher than normal incidence of rupture, though exact figures on this differ: French authorities put the rate at 5%, but in Britain it is thought to be around 1%, in line with industry standards.

California plastic surgeon Dr. Grant Stevens told CNN the health risks of industrial-grade silicone remained unclear.

“The PIP industrial silicone has many contaminants,” he said, but he added: “We’re not sure just how many… We can’t be sure what can go wrong.

“We know there’s an increased incidence of inflammation; we’re not certain of other health risks, but we certainly have concerns about cancer and other toxic exposures.”

Authorities in France and Britain have dismissed fears of cancer from the implants but have said that in case of rupture they could cause inflammation, scarring and fibrosis.

Where in the world were they used?

PIP was once the world’s third largest supplier of implants – 300,000 women in 65 countries around the world are thought to have had them fitted, both for cosmetic reasons and in reconstructive surgery following treatment for breast cancer.

The implants were widely used across Europe – 40,000 women in Britain are affected – and South America.

PIP silicone implants were never licensed for use in the United States.

British PIP implant recipient Rowena Mackintosh, told CNN she was worried about the potential impact on her health.

“It’s like a ticking time bomb inside me,” she said. “When you go to the doctor, you don’t say ‘who makes your medicine?’ – you just assume it’s going to be safe. To think that I’ve got mattress silicone inside me, and God knows what else they used, it’s disgusting.”

What advice is being given to women who had the implants fitted?

The advice given to women with PIP implants has varied widely from country to country.

France has urged all of those with the implants to have them removed immediately as a precaution. In Venezuela, authorities have also recommended the precautionary removal of implants.

The British government says there is no evidence to recommend the routine removal of PIP implants, though it says women who are concerned should be able to have them removed.

German medical groups have recommended that women seek the removal of their implants, but that there is no immediate danger.

Stevens argues that women who have had PIP implants should not wait until they rupture to have them removed.

“Waiting until an MRI is positive is like saying wait to run for cover until after a bomb goes off. If you know something is going to happen, you would try to remove the risk.

“I think it is incumbent on all women, regardless of their government’s stance, to recognize that they have a flawed, defective silicone product in their chest, and they have a shell that is containing it that is also flawed – they need to remove these implants, or remove and replace them.”

And what is being done?

The French government has offered to pay for the removal and replacement of all PIP implants fitted in France. Venezuela has said it will cover the cost of implant removal, but not their replacement.

In the UK, women who had their implants paid for by the National Health Service (NHS) will be able to have them removed free of charge, after consultation with their doctor. The British government says it expects companies that fitted implants privately, for cosmetic purposes, to offer the same deal.

Bioethicist Arthur Caplan told CNN it made financial and ethical sense for governments to pre-empt any potential health issues by removing the implants now, rather than waiting to see if they cause problems.

“If these things do turn out to be nasty, and do cause health problems, the bill for that is going to be big, and every government that has a nationalized system is going to pay, so it may be smarter, just on prudential grounds, to take them out now, avoiding what could be a huge financial disaster down the line.

“On the whole, I think it makes more sense, ethically and in terms of economic risk, to get these things out at public expense.”

What is the company’s response?

PIP went bankrupt in 2010, after its implants were banned. Its founder, Mas, is under investigation by French police. On Thursday, he was charged with involuntary injury over the implants.

But PIP’s lawyer, Yves Haddad, told CNN that while industrial silicone was used in its implants, no tests had shown them to be a danger – instead he insisted the problem was fear.

“Several things have heightened this fear: The advice and care given to victims, doctors who didn’t want responsibility and pushed the problem onto PIP, and the intense media pressure.”

Haddad also says there is no money for compensation for victims.

“Unfortunately the company has already been liquidated. No one can expect any money to come from PIP.”

Will the scandal have a lasting impact?

Concerns over PIP implants have led some to call for greater regulation of the plastic surgery industry.

“If it’s going in your body, if it’s a pill, if it’s a medical device, it should be regulated by the government,” said Caplan. “The consumer can’t tell what’s safe, what isn’t safe, what’s made according to good manufacturing processes.

“I think you have to have government watching over anything that people put into their bodies for a medical or a health purpose – I don’t buy the idea that it’s just buyer beware.”

The bioethicist said the scandal also showed the need for plastic surgery charges to include insurance against problems that may arise in future.

“For elective procedures… it would make sense to make part of the charge some kind of coverage or insurance if things go wrong, if there turn out to be adverse events,” Caplan told CNN.

“National health systems don’t want to pay for purely elective cosmetic procedures, so you’re going to be stuck if something does turn out to be fraudulent or just misused, and instead of turning to lawyers, it might make better sense to build some insurance into the system.”