Story highlights

"Sapeurs" are a Congolese sub-culture of dapper dressers

Despite usually working menial jobs, they wear expensive European labels

Daniele Tamagni snapped Sapeurs for his book "Gentlemen of Bacongo"

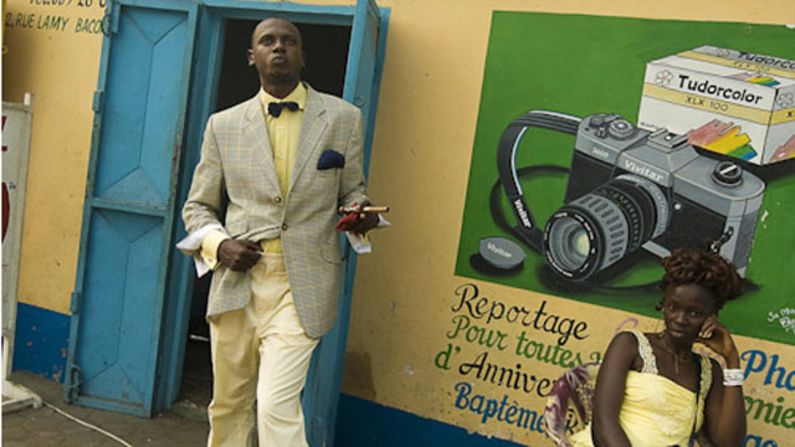

Sporting only the most stylish designer labels, wearing only meticulously matched colors, the Congo’s dandies are the very embodiment of sartorial elegance.

Known as “Sapeurs,” these dapper dressers are a Congolese subculture devoted to the cult of style. In Brazzaville and Kinshasa – the capitals of neighboring Republic of the Congo and the Democratic Republic of the Congo – they stand out among the widespread poverty, strutting the streets like walking works of art.

“It’s the fetishization of fashion – they are the worshippers of fashion, it’s their god, it’s powerful,” says Didier Gondola, author of “History of the Congo,” who has extensively researched the Sapeurs.

But for the Sapeurs – who are almost always men – it’s not about what’s in vogue, it’s about style. The labels they covet most are those that evoke classic elegance.

Suits by Yves Saint Laurent, Jean Paul Gaultier and Armani are all in demand, as are Japanese labels Kenzo and Yamamoto, says Gondola. When it comes to shoes, exclusive French label Weston and British label Church’s reign supreme. And imitations will not be tolerated.

“You can lose your reputation if you are wearing imitation,” says Gondola. “That’s something blasphemous.”

See also: Desert festival: Oasis for sounds of the Sahara

But these labels don’t come cheap. Gondola, who was born in the Congo and teaches history at Indiana University in the United States, explains that Sapeurs aren’t rich; they typically work menial jobs, and have been known to resort to shoplifting to feed their addiction to apparel. In Brazzaville, it’s common for Sapeurs to rent or borrow clothes from fellow fops or requisition them from friends visiting from Europe.

As the Congolese Diaspora has spread, so have the Sapeurs. They can now be found in European capitals including London, Brussels and Paris.

Dixy Ndalla, 30, was born and raised in Brazzaville, but has lived in London since the age of 17. He’s infatuated with the classic cuts worn by the British aristocracy and can spend £1,000 a month on new shirts and jackets.

“I am very passionate about clothing, I’m passionate about colors and suits,” he says. “In the winter it’s anything to do with tweeds, in the summertime a nice blazer, a beautiful pair of jeans, a beautiful shirt.

“I especially love Hackett, one of the top designers in the UK … Hackett suits start from around £600 and a bespoke made-to-measure will go out from £1,000 and upward.”

Ndalla travels back to Brazzaville in the summer and takes pride in showing off his very British attire.

“In the summer holidays, everyone goes to show their outfits,” he says. “They all meet in one street or bars and they all show their colors or the label of their suits … it’s up to people to judge and appreciate who’s dressed well.”

Once dressed in their finery, Brazzaville’s Sapeurs will often head to “Le Main Bleu,” a favorite bar, where they have informal contests. Each tries to out Sap each other with their combination of style, comportment and designer labels – known as “griffes.”

But Ndalla doesn’t consider himself a Sapeur, because he doesn’t dress up to compete with others. For him, it’s simply about taking pride in what you wear. “People from Congo love to dress up – it’s something that’s in my blood,” he says.

Although every Sapeur has their own unique style, certain looks are especially popular. Pastel-colored three-piece suits are a staple of the Sapeurs’ fastidiously assembled ensembles. They are finished off with a tie, cravat or bow tie – and the obligatory pocket square protruding from their immaculately tailored jackets. Cigars and pipes – lit or unlit – are de rigueur.

Italian photographer Daniele Tamagni stumbled across the Sapeurs when he travelled to Brazzaville in 2007. The next year he returned to photograph them, collecting his images in the book “Gentlemen of Bacongo.”

He says individuals often belong to sub groups within the Sapeur culture, such as the Piccadilly group, who dress in Scottish kilts.

“One member has a sister in Scotland who brings him kilts,” he explains. “They use and they adapt to their taste and individuality. They are masters of style, they create their own style.”

See also: Congo’s erupting volcano boosts tourism

Some disapprove of the Sapeurs spending what little money they have on the frivolities of fashion. But Gondola argues that being a Sapeur isn’t just about vanity – it’s a political statement.

In the 1970s “authenticity” was part of the state ideology in the DRC – a policy that prohibited the wearing of Western suits. The Sapeurs rebelled by wearing aggressively non-conformist clothes, including leather suits, says Gondola. To this day Kinshasa’s Sapeurs dress less conservatively than their suit-sporting Brazzaville brethren.

“The Sapeur is also about masculinity, politics, changing the stereotypes about how people view Africa,” says Gondola. “It’s about a lot of things, about beating the West at its own game, which is fashion: ‘You colonized us but we dress better than you.’”

Gondola says the history of the Sapeurs can be traced back to the 19th century, when the Republic of the Congo was a French colony. Some colonial masters would pay their servants in used clothes, and those servants would make a show of wearing their masters’ clothes on Sundays.

He adds that the phenomenon grew in the 1920s and 30s among Congolese nationals living in Paris – in particular Sap pioneer and anti-colonial activist André Matswa. But it really took off after independence in 1960, when ordinary Congolese people would travel to Paris and return home wearing the latest fashions.

In the 1970s, popular musician Papa Wemba, from the Democratic Republic of the Congo (formerly Zaire), began promoting the idea of the Sapeur, forming the “Société des Ambianceurs et Persons élégants,” or SAPE, of which many modern-day Sapeurs claim membership.

So what is the enduring appeal of the Sapeur? “It’s politics, spiritual, aesthetic, social – so many things,” says Gondola. “It’s a whole science – they are artists.”