Story highlights

There are only 800 mountain gorillas, found across two habitats in central Africa

The species is endangered, but their numbers are growing due to conservation efforts

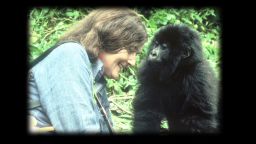

Rwanda's Karisoke Research Center was founded by the late zoologist Dian Fossey

Her mission continues there, with some gorillas she named still under observation

Hidden high among the forested volcanoes of central Africa, the mountain gorilla was unknown to science until 1902, when two were first encountered by a German explorer – and promptly killed.

It set the tone for the relationship. For much of the time since, due to deforestation and poaching, it has seemed the mountain gorilla was swiftly destined to be lost to the world again. Not long after the species’ greatest champion, the American zoologist Dian Fossey, was killed in Rwanda in 1985, there were fewer than 300 of the giant primates left in the wild.

These days, however, while the species remains endangered, their numbers have grown to nearly 800. This is due to the efforts of conservationists such as those working in Volcanoes National Park, in northwest Rwanda, where Fossey established a research center which continues to run in her name today.

Efforts to change attitudes towards the mighty animals have seen them become an important source of income for the local economy through the tourists they bring, and turned poachers into vocal advocates for conservation.

The world’s largest mountain gorilla population, thought to number less than 500 animals, is found in a mountainous region known as the Virungas, incorporating Volcanoes, Uganda’s Mgahinga Gorilla National Park, and Virunga National Park in the Democratic Republic of Congo. A second, smaller population can be found in the Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, in another region of Uganda.

See also: Rwanda’s conservation king

The Karisoke Research Center, operated by the Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund International and located in Volcanoes National Park, is the world’s most important facility for studying the mountain gorilla.

Veronica Vecellio, its gorilla program coordinator, said she developed the desire to work in her field after seeing “Gorillas in the Mist,” the 1988 film which popularized Fossey’s story.

“Studying Dian Fossey, it’s really clear how one person can really make the difference,” said Vecellio. “It’s what inspired me.”

Staff at Karisoke, which have observed the animals for more than 40 years, study the behavior of 10 groups of gorillas – including those initially named and studied by Fossey, and their offspring.

Vecellio said the center focused on new research topics every year – it had been able to learn, for example, that the life expectancy of a mountain gorilla was 35 years, as the animals had been under observation for their entire lifespan.

Fossey had believed in preserving the gorillas’ isolation by keeping tourists away. But today the tourism generated by the gorillas is essential to the local economy, and the organization that carries Fossey’s name is in favor of the visitors.

“It’s thanks (to) gorilla tourism that the gorillas are so well protected here in Rwanda,” said Vecellio. “I’m sure that if she was still there now, she would just appreciate the fact that thanks to the tourists, the gorilla (gets) to be alive. Before it was her keeping the gorillas alive, and now it’s the tourism.”

Fossey was found murdered in her cabin in the Virunga Mountains in 1985, and is buried in the park. Her killer has never been found.

See also: Central African gorillas may go extinct

Mountain gorillas are not frequently hunted for their meat, but can be maimed or killed by poachers leaving traps or snares for other animals. They have also been killed for their body parts to be sold to collectors.

Francois Ndungutse grew up in the area and used to hunt in the park. The former poacher says the last animal he killed was about eight years ago – these days he urges people to protect the park’s animals as part of their livelihood.

“We used to live near this volcanic park, depending on it,” he said. “At that time, we were very poor … we were relying on the park to get the meat.”

He said he and fellow poachers were persuaded to change their ways due to education programs from government agencies.

“In order to stop all this … poaching, deforestation or any other illegal activities, it was a combined effort of the former Rwanda National Parks and Tourism Office and the current Rwanda Development Board (RDB),” he said. “The RDB met us and gave us a plan of action and showed us how we can live without poaching in the parks.”

Vecellio said one of the amazing things about studying mountain gorillas was how close the primates let observers come to them, compared to other species she had studied.

“I started with western lowland gorillas, and the top distance was 50 meters to have them doing their activities,” she said. “But here you can approach a gorilla very close, and they ignore your presence … you can be there and just be a natural part of the forest and collect your data.”