Story highlights

Patrick Chappatte is the first non-American to win Overseas Press Club international cartoonist award

Chappatte a pioneer of cartoon reportage, or graphic journalism

Swiss-Lebanese cartoonist has also produced an animated film about cluster bombs

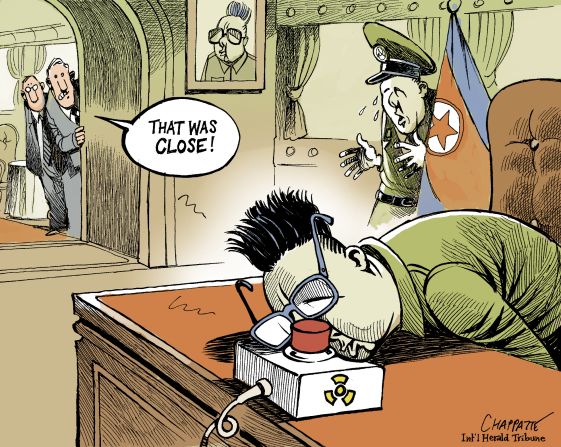

With frizzy hair still standing to attention, North Korea’s Kim Jong-Il drops dead, narrowly missing the nuke button as he slumps face-down onto his desk.

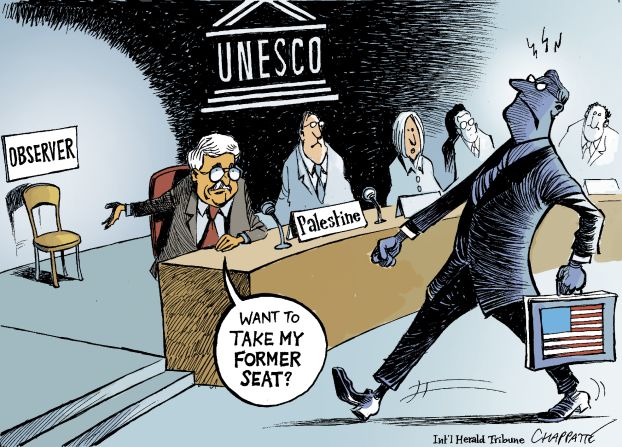

Welcome to the world of Patrick Chappatte – a cartoonist whose knack for summing up major global events in a few simple brush strokes this week saw him become the first ever non-American to win the Overseas Press Club of America’s international cartoonist award.

Chappatte will be familiar to regular readers of the International Herald Tribune, the global version of the New York Times, which prints his works of satire, slapstick and political comment on a daily basis.

But while his day job is producing illustrations to match the headlines, Chappatte is one of a new breed of cartoonists who do their own reporting; taking their sketchbooks and pens on to the front line of news gathering.

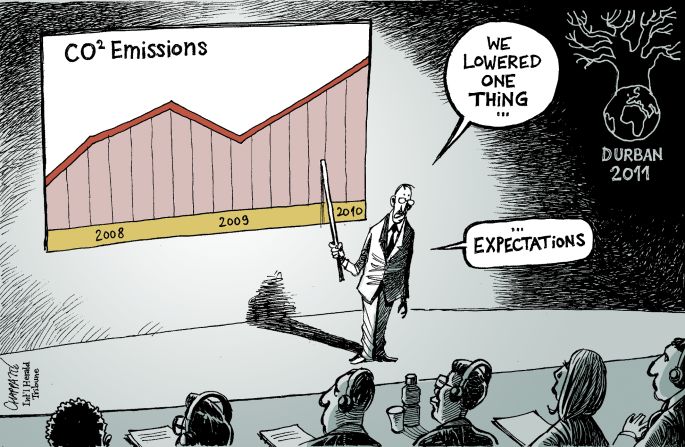

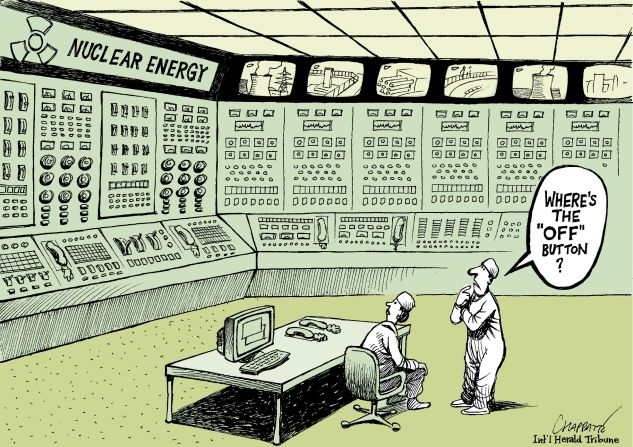

Such “graphic journalism,” says Chappatte, is often the most effective way of telling a story in a digital age where people are bombarded with information from all directions.

“Cartoons in their simplicity can help tell news stories and I think we will be using them more and more because they have a very special effect on people,” he told CNN by phone from Geneva, shortly before flying to New York to accept his prize.

See a high-res gallery of Chappatte’s prize-winning cartoons

“I personally feel the need to report and I feel that cartoons will help us in a world that is overwhelmed with videos and images where we’re dealing with so much information every day.”

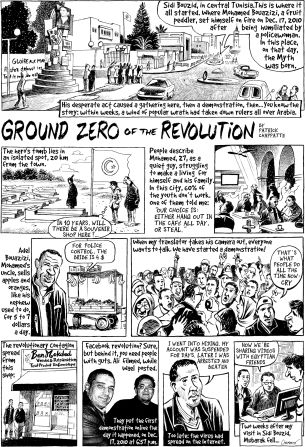

Among the dozen or so cartoons for which Chappatte is being honored is “Ground Zero of the Revolution,” a striking example of graphic journalism for which he traveled to Tunisia to record the story of Mohammed Bouazizi, the man whose suicide sparked the Arab Spring uprisings.

Chappatte also recently completed “Death in the Fields” a powerful animated film, produced with the International Committee of the Red Cross, that documents victims of cluster bombs in southern Lebanon. It is a project he hopes will lead to other similar work.

“People react very strongly in an emotional way in that kind of storytelling, so I see a lot of hope for that genre in the future,” he said.

Born in Pakistan to a Swiss father and Lebanese mother, Chappatte says he became an international cartoonist because he was an avid reader of newspapers in the numerous countries he grew up in.

After placing his first cartoon (about a man who broke out of jail for the seventh time) in a local Swiss newspaper at the age of 20, he worked his way to America, where he was employed first by the New York Times as an illustrator, then by Newsweek, which hired him to write a comic strip.

Chappatte then landed the IHT job in Geneva just a few days before the attacks of September 11, 2001, an event which tested his ability to “convey the feeling of America and the sense of the moment.”

He must have done something right because, as he points out with typical deadpan humor: “They kept me.”

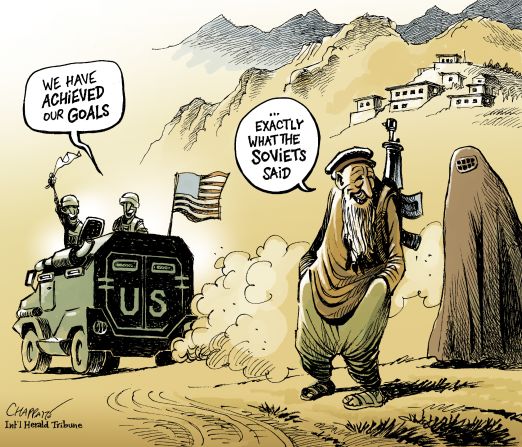

Chappatte puts his own success down to the ability to “translate into a simple idea and a few brush strokes the gravity or the reality of things… to show things as they are.

“When you look at it and say, that’s exactly it! That’s the best compliment people can give me.”

This is no easy task, particularly when the internet exposes cartoons to global scrutiny, as was the case in 2005 when the Danish newspaper Jyllens-Posten sparked controversy and demonstrations throughout in the Muslim world by printing a cartoon of the prophet Mohammed.

“That was the 9/11 of editorial cartooning,” says Chappatte. He says he is wary about causing outrage with his own work.

“We don’t all agree where the line is or where the balance is,” he adds. “I have a simple rule for myself. When I do a cartoon that can be seen as shocking for people, I want to be able to defend that cartoon eye-to-eye with the person that feels offended.”

While he describes the Jyllands-Posten episode as a “controversy of the internet age,” Chappatte – who has just returned from a graphic reporting assignment on urban violence in Guatemala – remains enthusiastic about the potential of cyberspace.

“The internet is full of possibilities in the language of cartoonists. You can do animated stuff and you can do multimedia stuff – a whole new range of creativity.”