Story highlights

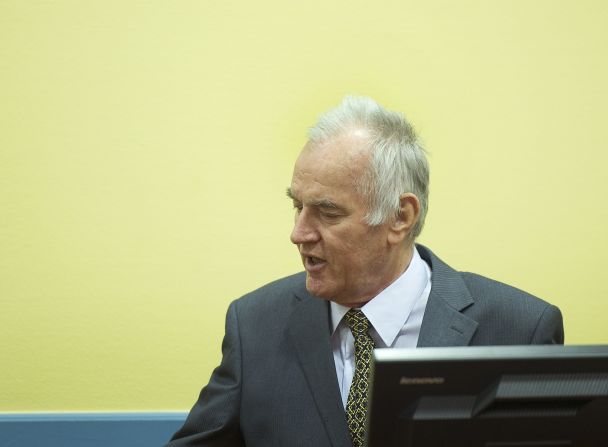

Former Bosnian Serb army commander Ratko Mladic on trial for crimes against humanity

Mladic is accused of being involved in slaughter of 8,000 Muslims at Srebrenica

Mladic is charged with leading 1992 siege against city of Sarajevo, an assault that lasted two years

Trial could usher in political backlash from Bosnian electorate, some of whom consider Mladic a hero

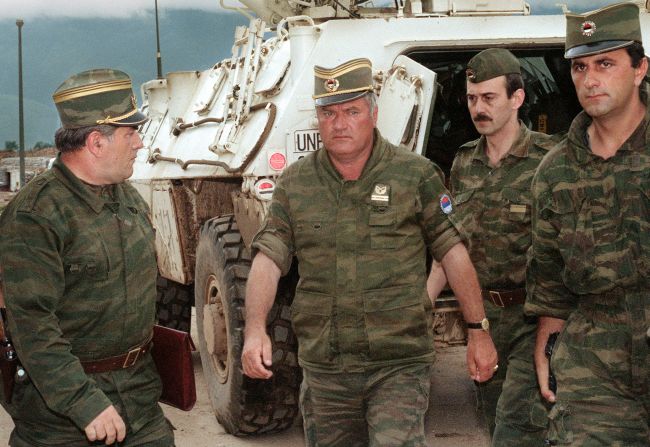

Ratko Mladic, the former Bosnian Serb army commander who went on trial Wednesday for crimes against humanity, is a notorious name synonymous with the dissolution of Yugoslavia, the Balkan wars of the 1990s and the bloody assaults on Sarajevo and Srebrenica.

During the five-day orgy of slaughter at Srebrenica, which Mladic is accused of being directly involved in, up to 8,000 Muslims were exterminated in what was described by the U.N. war crimes tribunal as “the triumph of evil.” A judge at The Hague tribunal described what happened there in July 1995 as “truly scenes from hell written on the darkest pages of human history.”

Born in Kalnovik, Bosnia-Herzegovina, during the height of World War II, the 70-year-old was a career soldier who served in Yugoslavia’s military before that nation dissolved in the early 1990s.

Mladic was shaped by the war when his father was killed by Croat Nazis when he was two years old. In 1965 he graduated from a military academy and joined the Communist Party in Yugoslavia, an ethnic stew of six states – Bosnia, Serbia, Macedonia, Slovenia, Croatia, and Montenegro.

Over the following three decades he rose rapidly through the ranks of the Yugoslav army. By the time he took Bosnia’s battlefields he had become a hero to many Serbs, seen as defender of their dwindling fortunes..

In May 1992, Bosnia’s Serbian political leaders picked him to head their forces and lead the assault on their enemies. Bosnia’s Muslim leaders wanted independence while the Serbs wanted to remain part of Yugoslavia – and the ethnic majority.

Mladic wasted no time galvanizing his heavily armed forces to besiege Sarajevo, cutting the city off from the outside world by shelling and sniping at its poorly prepared civilian population in the valley below them. More than 10,000 people, most of them civilians, were killed.

Over the course of the three-year war that raged across the whole country more than a quarter million people died, making the conflict the bloodiest in Europe since World War II.

A French policeman who collected evidence from Bosnian Muslims, Jean-Rene Ruez, told The Hague tribunal in 1996 that Bosnian Serb forces killed and tortured refugees in Srebrenica at will. Streets were littered with corpses, he said, and rivers were red with blood. Many people committed suicide to avoid having their noses, lips and ears chopped off, he said.

Among other lurid accounts of mass murder, Ruez cited cases of adults being forced to kill their children or watching as soldiers ended the young lives.

“One soldier approached a woman in the middle of a crowd,” he said. “Her child was crying. The soldier asked why the child was crying and she explained that he was hungry. The soldier made a comment like, ‘He won’t be hungry anymore.’ He slit the child’s throat in front of everybody.”

As the war ended in the fall of 1995, Mladic went on the run. Over the years, he eluded authorities while his cohort, Karadzic, was apprehended and is facing various charges at the court in The Hague. Their mentor, former Serbian President Slobodan Milosevic, died in jail in 2006 during his trial at The Hague.

Eventually, more than 16 years later, he was captured an hour’s drive from the Serbian capital living on a farm with a cousin. World leaders and human rights groups described the arrest as “historic” and “an important step forward.”

U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon called it a “historic day for international justice. This arrest marks an important step in our collective fight against impunity.” Interpol called Mladic “Europe’s most wanted war crimes suspect” while Amnesty International’s law chief Widney Brown said “at last the people who suffered have hope he will be brought to justice.”

The arrest meant a major hurdle that once stood between Serbia and its long-awaited entrance into the European Union was overcome, but the trial could also usher in political backlash from the country’s electorate, some of whom consider Mladic a hero.

Speaking to a Serbian Radical Party demonstration outside Belgrade’s parliament building immediate after the arrest, Darko Mladic described his father as “a freedom fighter.” The elder Mladic “defended his own nation, defended his people, which was his job,” his son said.

Robertson: Bosnia’s future is tied to justice

His family and lawyer have tried to use his poor health to prevent his extradition to the International Criminal Tribunal on the Former Yugoslavia in the Netherlands, but they failed.

In the court room at The Hague last year Mladic appeared to have lost none of his visceral dislike of his enemies. CNN’s Nic Robertson said he saw the defendant drawing his finger across his throat, “a gesture aimed directly at at some of the Srebrenica widows sitting in front of me, whose husbands he is accused of killing.”