Story highlights

Chelsea take on Bayern Munich in the final of the Champions League

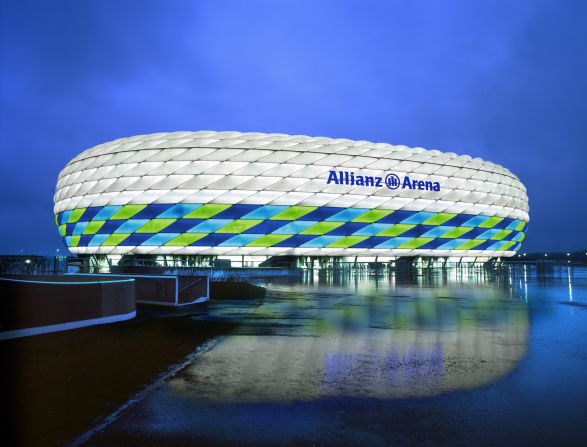

Bayern Munich will enjoy home advantage as final is hosted at Allianz Arena

Both clubs have drastically different ownership models

Chelsea is owned by a Russian billionaire; Bayern majority by the fans

When Chelsea and Bayern Munich walk out onto the pitch at the Allianz Arena for Saturday’s European Champions League final, it will mark the culmination of a competition rightly regarded as the finest – and the hardest to win – in club football.

Some of the greatest teams in the world have fallen by the wayside in race for the prize: Jose Mourinho’s Real Madrid and Alex Ferguson’s Manchester United, to name but two. It was also the last bow for Pep Guardiola, arguably the greatest coach in charge of the greatest team of the modern era, who left Barcelona shortly after Champions League semifinal defeat against Chelsea.

But it is much more than a match between the two best teams in Europe. It is also a clash of ideas over how football should best be run, and whether money and the success that statistically follows should trump the interests of the supporters.

Bayern vs. Chelsea: Click here to see the finalists’ vital statistics

On one hand you have Chelsea, a club which has benefited most from the financial liberalism of English football, an economic boom that followed the breakaway of the English Premier League two decades ago.

England’s laissez-faire economic approach meant that a young, unknown Russian oligarch who had only recently fallen in love with the beautiful game could purchase a club he had never visited and pump in hundreds of millions of dollars to secure trophies and league titles. Ticket prices rocketed as the game was gentrified, but Chelsea tasted real domestic success, winning three league titles, four FA Cups and two League Cups.

On the other side is Bayern. Derided as “FC Hollywood” by some supporters of its Bundesliga rivals due to the Bavarian team’s star-studded squad, it is still governed by the fan ownership model prevalent in Germany.

The “50+1” rule prevents rich foreign and domestic businessmen from taking over clubs.

Instead, the fans own the majority of the club (at least 50% plus one, hence the title). It keeps ticket prices low, and preserves the country’s football culture while ensuring the stadiums are full.

Anglo Saxon economics

Though the cheapest ticket for a top-grade match in Munich may well cost less than $20 – compared to over $80 at Chelsea – Bayern, and German clubs in general, have enjoyed far less success in Europe over the past decade compared to their English counterparts.

“In England, the change to football mirrored the wider free-market approach to business and the economy generally,” argues David Conn, a journalist for British newspaper The Guardian and a staunch supporter of the German model of ownership.

“State-owned businesses were privatized, and the football clubs were bought, floated on the stock market or sold on, and the few people who owned the shares made a great deal of money for themselves. Ticket prices have risen by around 1,000% since.

“German football is flourishing with the highest crowds in Europe and Bayern in the final. Yet they had no similar money-obsessed change to the way they had always done things. Bayern has 13,500 standing places, at €15 ($20) each, for top games.

“That is a great beacon for the collective way of running football, and gives the lie to the Premier League argument that selling the clubs to overseas buyers, making them available for people to profit from, and unleashing ticket prices to maximize income is a necessary basis for success.”

Premier League revolution

The introduction of the Premier League into English football in 1992 transformed everything.

Before then, English football was dying under the weight of hooliganism and indifference. The 1989 Hillsborough tragedy, where 96 Liverpool fans standing during a match were crushed to death, also had a huge impact. The tragedy led to the Taylor Report, which recommended all-seater stadiums be made compulsory.

In a stroke football found itself rebranded, with a new source of income thanks to Sky’s pioneering purchase of the English game’s television rights. But there was no mechanism to stop the rise of ticket prices to help pay for this bright new era of top-class players being paid six-figure weekly salaries.

Nor was there any true barrier to who could own a club. Like any other business in the UK, a football team could be bought and sold by anyone who could borrow enough money.

The global popularity made the Premier League popular to global businessmen and after Chelsea was sold to Roman Abramovich, the floodgates opened. Manchester City, which last weekend won the English title for the first time in 44 years, was bought in 2008 by Sheikh Mansour, a member of the Abu Dhabi royal family.

He in turn bought the club from former Thai prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra. Across the city, Manchester United was sold to the American Glazer family, owners of the NFL’s Tampa Bay Buccaneers, in a leveraged buyout – essentially by borrowing money they didn’t have. Currently half of the Premier League’s 20 teams are in foreign hands attracted both to its popularity and also the huge numbers involved.

Take the Premier League’s latest figures. As many as five billion people watched the 2010-2011 season but it is the prize money that is even more surprising. According to the Sporting Intelligence blog Manchester City took home over £60 million ( close to $100 million) for the season, with over half of that figure is in mandatory payments from TV rights. The bottom team, Wolverhampton Wanderers, still secured £39.1 million ($61.9 million).

The upside of money

Not everyone sees the downside of the glut of cash that has flowed into the English game.

“Because of fan influence, fans have prevented ticket prices from rising in Germany and they are 50% lower than in England,” argues Professor Stefan Szymanski, co-author of the book “Soccernomics.”

“But although tickets prices are twice as high (in England) almost exactly the same amount of people go to watch, and way more people watch second and third-tier football than in Germany. The money gets largely spent on players.

“The money does not go into the pockets of fat cats as the clubs make no money. England pays way higher wages than in Germany. You ask Manchester City fans what they think about large ticket prices, they’d be quite happy. You get more expensive players and far better performance.”

Szymanski points to English clubs’ relative success against German sides in the Champions League over the past decade. English teams have won 36 matches of 68 total encounters, German teams just 16.

“German fans complain bitterly that their teams are not competitive in Europe because other teams spend more money than they do,” he says, adding that financial transparency is also improved.

“I’ve got 95% of the published accounts in England between 1984 to 2010 – 3,200 sets of accounts. I physically possess them. England is totally transparent. In Germany, you just have to trust those running the club.”

A level playing field?

Not all German clubs are governed by the “50+1” rules. Wolfsburg and Bayer Leverkusen are both owned by corporations – Volkswagen and the pharmaceutical giant Bayer – while Hoffenheim has been bankrolled by a German billionaire who officially owns a minority stake but whose money makes the club’s continued presence in the Bundesliga almost entirely dependent on him.

And many German soccer fans would recoil in laughter at the thought that Bayern Munich is somehow the club of the people.

“It is not so much the ownership structure, it is that they are the superpower abusing their position, arrogant and systematically weakening all the other teams by buying the best players,” explains CNN contributor and Suddeutsche Zeitung correspondent Raphael Honigstein.

“Maybe the best comparison is with Manchester United 10 years ago, before the Glazers. They had a tremendous supporter base (Bayern boasts a fan base of over nine million in Germany alone) and there was hatred from them because of their success.

“It (the ’50+1’ rule) is good, it has symbolic value and does stop excess. But it doesn’t really stop people who really want to get involved and it allows for exceptions which angers clubs. It is not the promised land.”

Partial proof of this can be found in the remarkable success both clubs have in generating revenue. Although Bayern is 82% owned by fans (compared to 0% cent at Chelsea), according to the 2012 Deloitte Football Money League Bayern made £71.6 million ($113 million) more in revenue last year than Chelsea.

Bayern also has a brand new, state-of-the-art, 70,000-capacity stadium and can afford to sign top internationals such as Arjen Robben, Franck Ribery and Mario Gomez.

Winner takes all?

Both clubs made it to the final of the Champions League, but will whoever wins truly prove which model is best?

“I think a victory for Bayern is definitely a victory for the supporter-owned model of a club,” says Conn.

“(German clubs have) standing areas and affordable tickets, so young people and poorer people from all sections of society can still support football, as they have done since the game began – until 1992 in England.”

Of course, if Chelsea fans are celebrating on Saturday, they would beg to differ.

.