Story highlights

NEW: Charles Taylor aided "the most heinous and brutal crimes recorded in human history"

NEW: A victim recounted having to carry the severed heads of her own children

He was also found guilty of using "blood diamonds" to fuel a civil war and enrich himself

The former Liberian president sees himself as a victim of biased justice

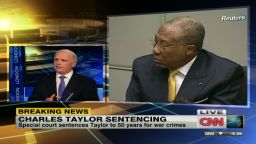

The first former head of state to be convicted of war crimes since World War II was sentenced to 50 years in prison Wednesday by an international court in The Hague, Netherlands.

The Special Court for Sierra Leone convicted former Liberian president Charles Taylor last month of supplying and encouraging rebels in neighboring Sierra Leone in a campaign of terror, involving murder, rape, sexual slavery and the conscription children younger than 15.

He was also found guilty of using Sierra Leone’s diamond deposits to help fuel its civil war with arms and guns while enriching himself with what have commonly come to be known as “blood diamonds.”

For victims in Sierra Leone, Taylor’s verdict brings relief

Taylor directed his gaze downward while Presiding Judge Richard Lussick read the sentencing statement, which began with a horror cabinet of carnage committed in Sierra Leone by rebels from the Revolutionary United Front, which the former president backed.

“The accused has been found responsible for aiding and abetting as well as planning some of the most heinous and brutal crimes recorded in human history,” said Lussick, who described one RUF military operation as the “indiscriminate killing of anything that moved.”

He spoke of amputations with machetes – some carried out by child soldiers forced to do so – and read accounts by witnesses who suffered under the violence.

Opinion: Do war crimes trials really help victims?

“Witness TF1064 was forced to carry a bag containing human heads,” Lussick said. “On the way, the rebels ordered her to laugh as she carried the bags dripping with blood.”

Upon arrival, “the bag was emptied, and she saw the heads of her children.”

A former child soldier, conscripted at age 12, in his testimony told of “having the letters RUF carved into his chest,” Lussick said. “When ordered on a food-finding mission to rape an old woman they found at a farmhouse, the boy cried and refused, for which he was punished.”

The prosecution had asked the Special Court for Sierra Leone to sentence Taylor, who was president of Liberia from 1997 to 2003, to 80 years behind bars, but the judges found the recommendation “excessive,” citing the “limited scope” of the conviction in key attacks.

The prosecutors had failed to prove that Taylor assumed direct command over rebels who committed atrocities.

There is no death penalty in international criminal law, and Taylor, 64, will serve out his sentence in a British prison.

The former Liberian president is appealing his conviction and will receive credit for time already served since his apprehension in March 2006.

The atrocities he was convicted of supporting occurred over the course of five years – almost his entire presidency – and reached a peak in 1998 and 1999. Sierra Leone’s civil war lasted from 1991 to 2002, ultimately leaving 50,000 dead or missing.

Although Taylor was not on the battlefield in Sierra Leone, the court saw his position of power as president of the neighboring country and the use of his own military’s capabilities to stoke up RUF rebels as making him directly responsible for the bloodshed he encouraged.

Taylor does not see himself as a war criminal but as a victim – a leader wronged by corruption and a hypocritical hand of justice with a political agenda.

“I never stood a chance,” he said last week during his final courtroom stand. “Only time will tell how many other African heads of state will be destroyed.”

Taylor accused the United States government of throwing the trial by paying prosecutors millions of dollars and claimed that witnesses had been bought.

He has expressed no remorse and insisted his intent was far from what had been portrayed by prosecutors. He has described himself as a peacemaker, saying he should be spared a harsh sentence.

His defense attorneys pointed to the former Liberian president’s role in the peace process that ended the civil war as a mitigating factor in his sentencing.

But after lengthy consideration, the panel of judges – which in addition to Lassick included Judge Teresa Doherty and Judge Julia Sebutinde – did not buy it.

“While Mr. Taylor publicly played a substantial role in this process … secretly, he was fuelling hostilities,” Lassick said, supplying rebels with arms and ammunition.

Last month’s landmark ruling by the Special Court for Sierra Leone against Taylor was the first war crimes conviction of a former head of state by an international court since the Nuremberg trials after World War II that convicted Adm. Karl Doenitz, who became president of Germany briefly after Adolf Hitler’s suicide.

Former Yugoslav President Slobodan Milosevic was tried by an international tribunal, but he died before a judgment was issued.

Taylor, 64, was found guilty of all 11 counts of aiding and abetting the deadly rebel campaign in Sierra Leone.

He was a pivotal figure in Liberian politics for decades and was forced out of office under international pressure in 2003. He fled to Nigeria, where border guards arrested him three years later as he was attempting to cross into Chad.

The United Nations and the Sierra Leone government jointly set up the special tribunal to try those who played the biggest role in the atrocities. The court was moved to the Netherlands from Sierra Leone, where emotions about the civil war still run high.