Story highlights

Euro 2012 kicks off on June 8, with 16 nations taking part

Buildup to the four-yearly tournament has been difficult for the co-hosts

There have been fears that infrastructure in Ukraine will not be sufficient

Country has also been criticized over human rights and racist football fans

If the pre-vote predictions had been accurate, football heavyweights Italy would be preparing to host the 2012 European Championship.

It wasn’t a shock on the scale of Qatar’s swoop for the 2022 World Cup, but the joint bid from Poland and Ukraine was at one stage considered third favorite to host Euro 2012 – out of three candidates.

But taking advantage of the hooliganism and match-fixing allegations making ugly headlines in Italy back in 2007, Poland and Ukraine stole up on the outside to pip both the 1968 champions and another joint bid from Hungary and Croatia to the honor.

Racism, rather than Ronaldo and Ribery, dominates Euro 2012 storylines

Fulfilling UEFA chief Michel Platini’s ambition of balancing the power in European football, this will be the first major football tournament in the former Iron Curtain.

But as early as 2008, Platini was telling Ukraine to “get going” as the building of new stadiums and improvements in the transport network slipped behind schedule. At one stage, there was even talk of Scotland stepping in as emergency host.

By the end of 2011, Platini was diplomatically describing the buildup as a “complicated adventure.”

“Difficult births often lead to beautiful babies,” the French football great concluded in March as Poland and Ukraine finally declared they would be ready for the June 8 kickoff when an estimated worldwide audience of at least 150 million is expected to be watching.

Only time will tell whether Platini will return to UEFA’s headquarters in Switzerland a proud father.

Most major sporting tournaments experience a rocky buildup, Poland and Ukraine’s has been at the turbulent end of the scale – understandably so, given the countries’ lack of major event experience coupled with ambitious improvement plans that are reported to have cost $38 billion combined.

The stadia are breathtaking. Five of the eight on show during the tournament are brand new, and the existing venues in Kiev, Donetsk and Kharkiv have undergone major developments.

The 50,000-capacity, newly-constructed National Stadium in Warsaw will host the opening game between Poland and Greece.

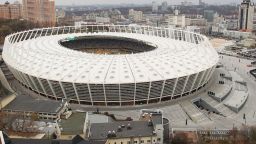

Kiev’s 60,000-capacity Olympic Stadium, which began life in 1923 as the Red Stadium of Lev Trotsky and hosted games during the 1980 Moscow Olympics, has been completely renovated with a new transparent roof and will host the final on July 1.

While the venues have been tested, the transport network will come under scrutiny for the first time when an estimated one million fans descend on the two countries.

Ukraine faces a race against time to complete the planned 1,750 kilometers of new roads in time for the start of the tournament. It has also shipped in high-speed trains from South Korea to ease travel between the two host countries.

Poland has already accepted that some of its transport improvements – including the construction of 750 km of new motorways – may not be ready.

“We know not everything will be completed in time for Euro 2012,” Poland 2012 communications director Mikolaj Piotrowski told CNN late last year.

“But today we can say that a lot of important investment projects will be completed three to five years sooner than without the Euros scenario, so I think it was worth it to see Michel Platini opening the envelope in Cardiff in 2007.”

If getting around should be manageable for fans, finding somewhere affordable to stay once they get to their destination is an altogether trickier task.

England – traditionally one of the best-supported European teams – failed to sell out its original allocation of tickets for its group games in Kiev and Donetsk, with many fans opting to stay at home as Ukrainian hotel owners seek to make hay from the tournament by ramping up prices. In April the Football Supporters’ Federation said fans were being quoted as much as $1,000 a night for a three-star room.

The England team avoided that problem by choosing a base in Krakow, Poland – even though it will mean thousands of miles of travel between the two countries.

If it isn’t financial concerns putting off fans, it is the fear of the kind of reception they’ll get. The English Foreign Office warns that there has been a recent “increase in hostility” toward gay people in Ukraine and that “travelers of Asian or Afro-Caribbean descent and individuals belonging to religious minorities should take extra care.”

The families of black England players Theo Walcott and Alex Oxlade-Chamberlain have already decided against traveling to Ukraine – and that was before a BBC documentary highlighting racism and violence in the host countries was screened

“It’s a major concern,” said Oxlade-Chamberlain’s father Mark, himself a former England player. “I think your safety is more important than a game of football.”

Poland, too, has suffered serious problems with racism.

“Monkey chanting, banana throwing, that has happened in Polish matches unfortunately,” Rafal Pankowski from the campaign group Never Again told CNN.

“We want to use the Championships to highlight some of the issues and make a difference in a positive way in terms of anti-racism education.”

A series of bomb blasts in Dnipropetrovsk, Ukraine’s fourth largest city, in late April only added to the pervading nervousness over traveling to the country, while several EU leaders will boycott the tournament over Ukraine’s treatment of imprisoned opposition leader Yulia Tymoshenko.

Amnesty International, meanwhile, has warned of “widespread police criminality” in Ukraine, leading to concerns that any crowd trouble could be met with a particularly brutal response.

UEFA has always accepted that giving Euro 2012 to Poland and Ukraine was a risk.

“From the beginning, it was a big challenge to go to Poland and Ukraine,” Platini told CNN last month. “Four years ago when all the signs were red, red, red – stadium, roads, accommodation – it was not easy.

“But I say it was a good risk.”

And Kiev could witness a historic moment if Spain can follow up 2008’s victory and become the first team to successfully defend the title since the tournament began 52 years ago.

On a lighter note, we await the predictions of Ukraine’s “Psychic Pig” and Poland’s “Citta” the elephant with interest. They follow in the footsteps of 2010 World Cup soothsayer Paul the Octopus in what seems to be becoming a curious tradition at major football tournaments.

For most pundits, the Spanish are favorites for the title, but they have their problems. Record scorer David Villa and veteran defender Carles Puyol have been ruled out of the tournament, while striker Fernando Torres – who netted the only goal of the 2008 final – has endured another torrid season for Chelsea.

Their competition looks set to come from Joachim Low’s youthful Germany side, 2010 World Cup finalists Netherlands, and perhaps a France team that appears to be back on an even keel under the calming influence of Laurent Blanc.

Italy, six years on from the scandal that so seriously damaged the country’s chances of hosting the tournament, is embroiled in another match-fixing crisis that led defender Domenico Criscito to be cut from the squad.

The English are even less fancied, particularly so among their own pessimistic supporters. Roy Hodgson took up his coaching job just 29 days before the first game against France and has to get the best out of a squad that must survive the first two games without the suspended Wayne Rooney, one of the team’s few world-class players.

As for the hosts, Poland looks to have the easier group with Czech Republic, Greece and Russia.

Ukraine must contend with France, England and Sweden. For 35-year-old national icon Andriy Shevchenko, the tournament is a chance to put the perfect full stop on a 17-year international career.

“Ukrainians, our time has come!” declares the team’s slogan.

UEFA might be hoping it also applies to the country as a whole.