Story highlights

Wimbledon is the oldest tennis tournament in the world

It began in 1877; defending champion Novak Djokovic hails its "tradition"

The tournament is a powerful brand exporting one aspect of "Britishness"

But is Wimbledon still a relevant reflection of the country today?

Britain hosts a sporting event over the next fortnight that manages to combine every conceivable stereotype associated with the nation – rain, royalty and heroic British failure.

Wimbledon follows the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee – when Britons, with Union Jacks in hand, stood in the pouring rain as the monarch cruised past in a barge on the Thames – and a day after the exit of England’s soccer team from a major international tournament – as so often before on penalties – after defeat by Italy in Euro 2012.

Since its inception in 1877 the All England Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club in a small, affluent suburb of south west London that gives the event its name, has presided over a tournament – the oldest and grandest on the tennis circuit – that has become more than simply another fixture on the grand slam calender.

Royal regulations for Ascot’s fashionistas

The quaint images and traditions of The Championship – of regimented ball boys, pots of strawberries and cream, lines of well-mannered fans politely queuing for their tickets, players bowing or curtsying if the Queen is attendance in the Royal Box – have become as ubiquitous as the tennis.

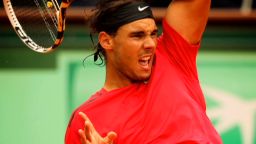

Overseas players like Novak Djokovic cannot get enough of the tournament’s history.

“The great thing about Wimbledon that I really appreciate is the tradition that is respected and protected for more than 130 years,” defending men’s champion Djokovic declared yesterday on his Facebook page.

“We still wear only white clothes during the tournament, and the defending champion always plays at 1pm on Monday!”

And for the millions of people that will watch Wimbledon around the world – and it is estimated that that the global TV audience could be as high as 500 million – the tournament also reinforces what many think constitutes Britishness.

“It has a David Niven-ish propriety (in that) it conforms to standards of behavior that were accepted … at least during Niven’s time (in the 1950s,)” explains Professor Ellis Cashmore, an academic and social commentator whose most recent work looks at whether Britain is losing the civility that it is famous for.

“They still refer to ‘Ladies’ and the scoreboard [until recently] reads initials rather than Christian (first) names; the players have to wear white, and the match referee, not umpire, wears his club blazer.

“So, there is an old-school sort of Britishness … And we shouldn’t forget the time-honored convention that Brits never win. Well, not since 1977, and not in the foreseeable future.”

Brand Britannia

Since that victory for Virginia Wade 35 years ago – and you have to go back to 1936 and Fred Perry to find a British men’s singles champion – the story of Wimbledon has been one of sporting failure for its hosts. Yet the power of the Wimbledon brand to shape what the rest of the world thinks of Britain remains.

“Wimbledon is a global brand: it’s internationally recognized in a way that the U.S. Open and the French yearn for,” explains Cashmore.

“In terms of reach, Wimbledon runs the (English) Premier League a very close second. The name itself resounds like a thunderclap. There is nowhere on earth where you can just say ‘Wimbledon’ and people won’t know what you’re talking about.

“It’s like the BBC: an emblem of Britain that commands respect and admiration near and far.

“But emblems are not necessarily accurate reflections of reality. they are representations, images or symbols of an ideal; a perfect place where people wear straw hats, eat fresh strawberries with their champagne and hobnob with the royal family.”

For social commentators like Peter York – author of the famous “Sloane Ranger Handbook” – Wimbledon represents a type of Britishness that doesn’t exist any more: one steeped in glorious Empire that is overwhelmingly white, affluent and still centered around London and the south east of England.

“Wimbledon mildly confirms that tennis around the world is quite a polite middle class game played in a very restrained way with a very restrained audience. People don’t get into any fervor. That’s for other proletarian sports,” he says.

“It’s a middle class sport wherever you go … It’s all nice enough (and) reinforces British imagery but not create it. It’s definitely a very southern (British) thing, a very southern suburb. It’s a southern, well off, late Victorian suburb with a particular social character.”

Cashmore agrees that Wimbledon reflects only a very tiny aspect of British society, and one that still fails to reflect the changing multicultural character of the country that surrounds it.

“(Wimbledon represents) only one of many types of Britishness,” he says.

“Football, boxing and athletics represent another type of Britishness, one in which the competitors are black, Asian as well as white, and who come from all kinds of class backgrounds.

“If Wimbledon is going to be derided, it’s because it seems remote and insulated from this type of Britishness.”

The last great British hope?

Whether Great Britain itself survives the next few years is another question entirely. This year the hopes of the host nation once again rest on Andy Murray’s shoulders. He will also represent Great Britain at this summer’s London Olympics.

Yet Murray is also Scottish and Scotland will be voting on the issue of independence in the summer of 2014. The country’s one viable hope for victory in the foreseeable future might be playing under a different flag in 2015.

Such is the confusion over national identity – a debate centered on the conflict between British identity and that of its constituent English, Welsh, Scottish and Northern Irish nations, not to mention the influences of cultures from outside the realm – that Prime Minister David Cameron has spoken about the need to be more muscular in promoting an idea of what Britishness actually is.

This year he has plenty of opportunities to do that following the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee, now Wimbledon and next month at the Olympics. But perhaps as the poet and author Bonnie Greer recently said: “I don’t know what it means to be British and I think it’s a very positive thing.

“Britain is the right sort of template for the 21st century in that it is a multinational state that isn’t at war with itself, that isn’t tearing itself apart, and is actually showing the world how to function.”

In that version of Great Britain, there’s plenty of space for an event like Wimbledon.

“Wimbledon still maintains its specialness,” agrees Cashmore. “There is no longer a single, unified conception of Britishness that’s good for all times.

“Wimbledon embodies one image. It is nobody’s idea of all-things-British.”