Editor’s Note:

Story highlights

Exclusive look inside a gym deradicalizing terror convicts with cage-fighting lessons

Cage-fighting sessions allow the instructor to question radical thinking

British officials are looking to see if the techniques could be adopted on a large scale

But the method -- with a 100% success rate -- is also very time consuming

In the shadow of London’s Olympic stadium, home of the Summer Games, is a hotbed of radical fundamentalism dubbed Londonistan, from where al Qaeda has already recruited for some of its most ambitious plots.

In past months, dozens of convicted terrorists have been released in the UK, including onto the same London streets. Seldom since 9/11 has al Qaeda, though weakened, had such an opportunity to create carnage on the global stage.

At the same time a no-holds barred fight for security is under way. It is unorthodox, but British officials say it is working, producing results which have never been seen before – and at its epicenter is a veteran Muslim cagefighter.

Over the last six months Usman Raja gave CNN exclusive access to his pioneering work; speaking for the first time about his work with former terrorists.

In the past two years more than 50 convicted terrorists have been released from British jails after serving their sentences, producing a major headache for British security services.

Read about some of Raja’s success stories

“Unfortunately, we know that some of those prisoners are still committed extremists who are likely to return to their terrorist activities,” Jonathan Evans, the director of British domestic intelligence service MI5, warned two years ago.

The task of managing the re-integration into society of these young men has proved beyond the capabilities of most Muslim community groups. But one east Londoner, proud to be both British and Muslim, has felt religiously compelled to take on the fight.

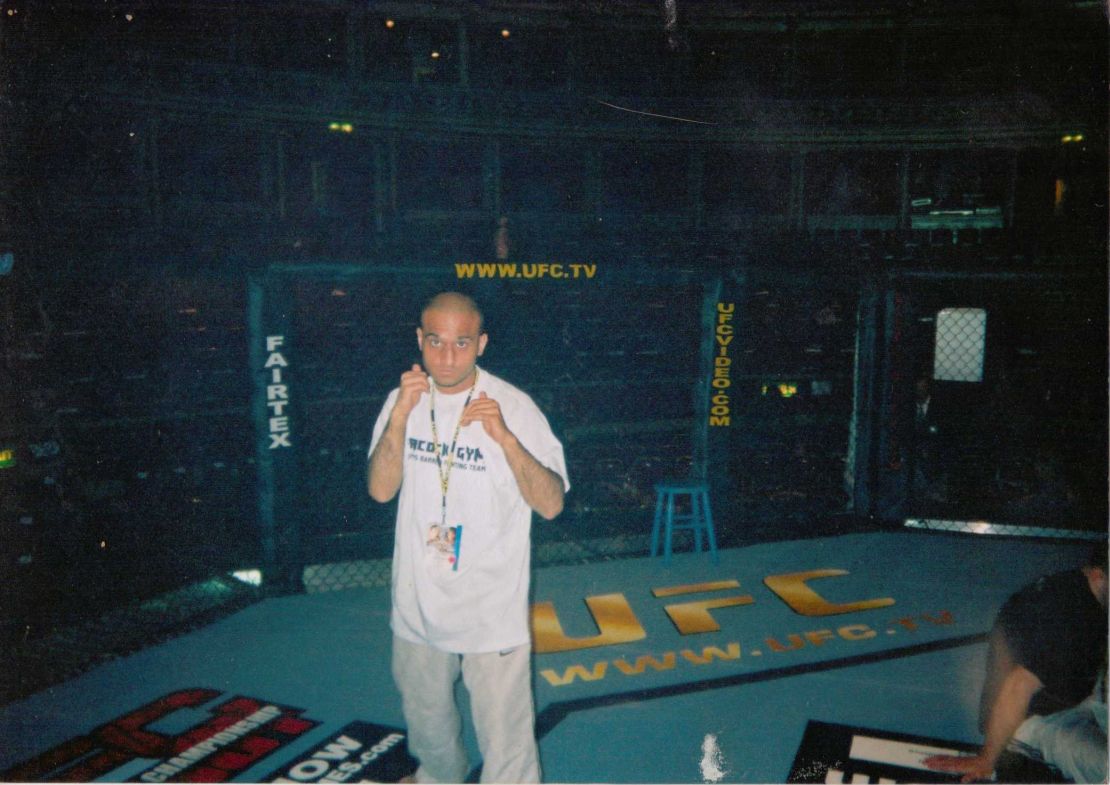

Raja, the 34-year-old grandson of a Pakistani immigrant is not tall but he is built like an ox, with a close shaven head, short beard, and otherwise pure muscle. On his thumb he wears a ring with a curving metal spike, a legal form of self-protection, which he says is extra insurance if extremists try to physically confront him.

Raja is one of the UK’s most renowned cage-fighting coaches, having fought in arenas across the UK during the early gritty years of the now fast growing sport, also known as mixed-martial arts (MMA).

He is also a man of deep ideas, including harnessing Islamic teaching to defeat the ideology of the terrorists.

Three years ago, Raja began taking under his wing some of the most dangerous offenders being released from the highest security wings of the British prison system; men convicted of carrying out terrorism on behalf of al Qaeda in murder, assassinations, bombing, and arson plots.

His aim was to rehabilitate them into mainstream society.

Last year pictures of several of the men appeared in full page splashes in British newspapers warning of the threat posed by released terrorists to the Olympics. “Games Fear Over Evil Fanatics” declared one headline.

A ‘humiliating’ security failure

The release of dozens of convicted terrorists was reflective of lower sentences under British law for a range of terrorist offenses, compared to the United States and some other countries.

Of the 250 convicted of terror offenses in the years after 9/11 relatively few received sentences of 15 years or more, says Michael Clarke, the Director General of the Royal United Services Institute and an advisor to the UK government on counter-terrorism.

Clarke told CNN that it was not unusual for terrorism suspects to be charged with more minor offenses than their plots merited, because British intelligence services were hesitant about intelligence emerging in court which could be useful to al Qaeda.

Raja tried a novel approach with some of the most challenging freed convicted terrorists; he coached them cage-fighting skills.

Raja says it proved a remarkably effective way of breaking them out of their pro al Qaeda mentality and opening up their minds to his counter-extremist message.

It has almost literally involved knocking sense into them in the fighting gym.

Convicted terrorist calmed by cagefighting

When the released convicts meet Raja to train in gyms in and around the capital, including one in east London within sight of the Olympic park, they are very much on his territory. Sparring in the cage, he says, has a way of focusing the mind.

“Any idea you’ve got of yourself will be challenged as soon as you come in here,” Raja said. “Once that idea of yourself is challenged and that opening happens we are able to go in and start dismantling that perception.”

He says he has used cage-fighting sessions in about one-third of his intervention cases. As well as working with released convicted terrorists he has worked with dozens of young Muslims radicalized in jail.

The MMA gym, he says, has been a big draw for the previously jailed terrorists, for whom physical training was both an outlet and a form of protection in prison. And he says his coaching naturally allows him to develop a mentoring relationship.

Once he has their attention, he impresses on them that true Islam is spiritual, tolerant and humanistic, and not the narrow-minded, divisive message of hate peddled by self-serving radical preachers.

“I try to unravel their Jihadist identity. Previously that identity was being validated. I say to them let’s question that validity,” Raja said.

That identity, Raja says, is the result of a “deviant Jihadist subculture” that has been accepted by too many young British Muslims which justifies all manner of criminal activity, including terrorism, out of hostility to the British state.

Read Raja’s path to anti-terror inspiration

British officials say Raja’s approach is working. The former cagefighter has worked with 10 of the dozens of convicted terrorists released from prison and says that his approach has been successful so far in every single case.

“He’s the most successful guy out there doing this sort of work,” said a UK Home Office official, aware of Raja’s work but who did not want to be named given the sensitivity of ongoing cases. “He has that ability to inspire; that personality X-factor.”

Clarke told CNN: “Raja’s 100% success rate is based on his own skill, his acknowledged skill, his understanding of what people are motivated by but also because he has got the time, effort and commitment to spend on individual people.”

The Probation Service’s Central Extremism Unit, the lead UK government agency dealing with released terrorist convicts, now regularly channels cases towards Raja.

The young men are not required to meet him, but are encouraged to do so. Other terrorist convicts up for release, having heard about his work, reach out to him directly. Several of those Raja is working with are still considered potentially dangerous.

But Raja knows how to connect. Like several of them, he is also from the tough neighborhoods of east London, once subscribed to fundamentalist views himself, and says he came close to fighting Jihad in Bosnia in the 1990s.

“They see someone who is coming from the same type of background who can understand what may have brought them to the place they are in,” Raja told CNN.

Raja says they are impressed by his martial arts pedigree and sense he sincerely wants to help them.

What adds to his credibility is that he has not been beholden financially to the British government.

Almost all his work is self-financed under the auspices of the Unity Initiative, an organization which he runs with his wife and a small band of helpers. Funds have been so scarce he says he finances the work from his cage-fighting coaching and his wife’s student loans.

Check out CNN’s Security Clearance

But theological fire-power also has a crucial role in his success.

When he and his wife Khadija founded Unity in August 2009 they created a systematic approach for working with radicalized Muslims, which they based on the teachings of Raja’s guru Sheikh Aleey Qadir, a Malaysian cleric resident in east London from a school of Islamic learning that says it traces its lineage of learning directly to the Prophet Mohammed.

The cleric’s backing has provided crucial religious legitimacy to their efforts and Qadir has played a hands-on role supporting Unity, including counseling several of the released men. One of his protégés, Wael Zubi, a young British-Libyan theologian, is also an instrumental volunteer member of Unity.

“I don’t look at it as de-radicalization. What we are doing here is a 1,400-year-old methodology,” Raja told CNN.

“The reason they haven’t slipped back is because of the legitimacy of the message. You can’t argue if you say through my teacher we have a lineage going all the way through Islam back to Prophet Mohammed,” Raja added.

While he focuses on the men, Khadija, a Hindu convert to Islam, is working with young women who have become radicalized, including some released from jail after being convicted in terrorism cases. One was convicted in connection to a failed London bombing attack.

Often the Rajas work in tandem: he works to de-radicalize the husband, she to change the views of the wife. Sometimes when radicalized men are reluctant to meet Raja, Khadija has been able to reach out to their wives.

“You have to have a joined up approach,” said Khadija, who has a beaming optimism and eloquence. “I really believe the women aspect has been totally overlooked mainly through short sightedness because that is where the future of this is going to be with the children, with the mothers.”

The stakes in Raja’s work are high because if those being released from prison maintain their radical views they could become magnets for pro al Qaeda extremists.

Michael Clarke, the UK government counter-terrorism advisor, said: “The biggest problem we have with radicals coming out of prison is not that they will commit another act but they will act as an inspiration for clean skins – people who have not committed terrorist acts in the past – to then go and do something.”

He added: “The fact that we have the Olympics in 2012 was never thought about when people were being locked up for terrorist offences in 2005 or 2006 and there is no way under the British system you can keep them in prison because the Olympics is on.”

The east London neighborhoods just beyond the Olympic village are where a significant number of the ex-con terrorists call home.

The al Qaeda cell that plotted to bring down nine transatlantic airliners in 2006 planned their operation from these streets, as did the ringleader of a 2010 plot to target the London Stock Exchange and other London buildings.

In late June, two east London Muslim converts were arrested on suspicion of plotting an attack against the Olympics canoeing venue, but were subsequently released without charge. Earlier this month seven London residents, including three brothers in the Olympic area of Stratford, were arrested in an ongoing investigation into a suspected terrorist plot.

Three of those arrested, including one of those living in Stratford, were charged Wednesday with preparing for acts of terrorism. At least one of those arrested in July was a follower of one of Britain’s most notorious Islamist extremist groups, which is based in the east London area, and whose followers openly sympathize with al Qaeda. Some of them have been tied to terrorist plots to bomb London.

Known for many years as Al Muhajiroun, the organization has operated under a variety of names in recent years because of successive British government bans, but is still active. In recent weeks followers have been distributing radical leaflets outside the London Underground stop adjacent to the Olympics. The group’s controversial leading figure is Anjem Choudary, 45, a British-Pakistani from east London, who trained as a lawyer and has been careful to stay on the right side of the law.

Several of the recently released terrorist convicts, including at least one Raja is working with, moved in al Muhajiroun circles before their arrest, and the concern is they may be drawn back.

Choudary told CNN he believes militants who have already served prison time may be more difficult to deter and he insists that terrorist convicts are an inspiration even before they get out of jail.

“They have a huge amount of respect in prison. People want to listen to them, people want to embrace Islam at their hands,” stressed Choudary.

Raja is under no illusion of the challenge as he takes on new cases and visits convicted terrorists in some of Britain’s highest security jails. “They are in a reactionary mind-set. Some of them are very angry,” he told CNN.

Raja says if Unity can successfully expand the model, it may be possible to wean a generation away from the lure of extremism. But fail and the potential for terrorist attacks in the UK could increase and tensions grow between Muslim communities and mainstream British society.

Clarke, the government advisor, says the scale of the challenge means that Raja can only be part of the solution.

“There is no question the Unity Initiative is known for its success, and of course all credit to it for that, but that success is at very low numbers, and the sheer commitment of time for every single individual being addressed means the initiative would have to be much wider. You’d have to do it on an industrial scale to have any hope of success,” Clarke said.

“The numbers defeat you – if the numbers we are talking about being radicalized are in the hundreds, the numbers being de-radicalized are in the dozens,” Clarke added.

“What is not clear is the degree to which it depends on his inspirational personality: the question is can it be scaled up?” a UK Home Office official told CNN.

Usman and Khadija Raja are looking for backing from British Muslim businessmen and other donors for funding because they believe it is important to keep autonomy from the British government.

They believe that if they can get more backing over time they can build up the efforts of Unity significantly, and provide others around the world a blueprint to rehabilitate even the most extreme of Islamist militants.

“There is a real problem here and it’s growing and it would be incredibly sad that we have the cure and then it’s not delivered and it’s not given the platform it needs to be dispersed. At the end of the day I’m still a mother and I don’t want to live a world where there is this very real fear,” Khadija Raja told CNN.

CNN’s Ken Shiffman contributed to this report.