Story highlights

Radovan Karadzic found guilty of 10 of 11 charges, including genocide over Srebrenica massacre

The "Butcher of Bosnia" was the leader of the breakaway Serb Republic in Bosnia in the 1990s

A trained psychiatrist and published poet, he spent a dozen years on the run before trial

Radovan Karadzic, whose Interpol charges listed “flamboyant behavior” as a distinguishing characteristic, was a practicing psychiatrist who came to be nicknamed the “Butcher of Bosnia.”

On Thursday he was found guilty of genocide and other crimes against humanity, in what was seen as one of the most important war crimes trials since World War II.

A special U.N. court in The Hague, Netherlands, sentenced the 70-year-old to 40 years in prison for his participation in four “joint criminal enterprises,” including an overarching plot from October 1991 to November 1995 “to permanently remove Bosnian Muslims and Bosnian Croats from Bosnian Serb-claimed territory.”

He was found guilty of 10 of the 11 charges against him, including extermination, persecution, forcible transfer, terror, hostage taking and genocide.

The latter charge related to his role in the Srebrenica massacre, in which more than 7,000 Bosnian Muslim men and boys were slaughtered by Bosnian Serb forces under his command.

As the leader of the breakaway Serb Republic in Bosnia, Karadzic commanded troops who carried out widespread massacres of Bosnian Muslims and Bosnian Croats during a campaign of ethnic cleansing in the former Yugoslavia.

The verdicts – which can be appealed – are the result of a trial process that began in 2008, when he was arrested after 12 years as a fugitive.

Rise to power

Karadzic was born on June 19, 1945, in Petnjica, Montenegro. He studied psychiatry and medicine at the University of Sarajevo during the 1960s and took courses in psychiatry and poetry at Columbia University from 1974 to 1975.

Karadzic, a Serb-Croat, in 1990 helped found the Serbian Democratic Party, a party aimed at unifying Serbs into a common state, and became its president.

Two years later, he became president of the newly declared Serbian Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina, later called “Republika Srpska.” During the next three years, he ordered Bosnian Serb forces to seize the majority of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

He also announced, according to his U.N. indictment, six “strategic objectives” for the Serbian people. They included the establishment of state borders between the Serbs and the other two ethnic communities, Bosnian Muslims and Bosnian Croats.

Answering to him, according to the indictment, was Bosnian Serb military commander Ratko Mladic.

From May 1992, the indictment said, Bosnian Serb forces under Mladic’s command targeted civilian areas of Sarajevo with shelling and sniping during a three-year conflict within the city.

In July 1995, according to the U.N. indictment, troops under Mladic’s command executed an estimated 8,000 Bosnian Muslim male prisoners in Srebrenica, a U.N. safe area, and then participated in a comprehensive effort to conceal the killings. The massacre is considered the worst in Europe since World War II.

The indictment states that Bosnian Serb forces acted under Karadzic’s direction and worked to “significantly reduce the Bosnian Muslim, Bosnian Croat and other non-Serb populations” in municipalities that were seized.

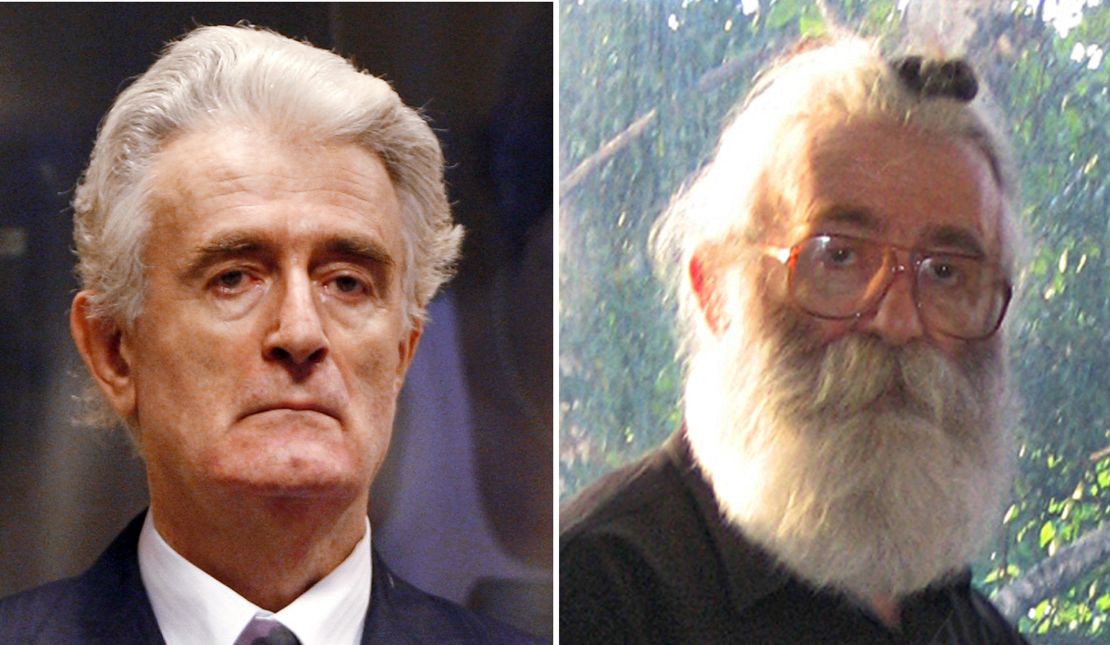

Years in hiding

Karadzicdisappeared from the public eye in September 1996, a year after the Dayton Peace Accords brought a formal end to the conflict and banned anyone accused of war crimes, including him, from office.

He reportedly shaved his trademark bushy hair, grew a beard and donned priest’s robes, moving from monastery to monastery in the mountains to avoid capture.

CNN correspondent Alessio Vinci said in 2008: “He enjoyed protection from the local population, wherever he was hiding. Legend has it he disguised himself as a priest to take part in his mother’s funeral.

“In 2002, after NATO launched one of its many failed raids to try to arrest Karadzic in Bosnia, I interviewed his mother. At that time she said: ‘Serbs are righteous people and I can see that they support him, and that they adore him the way he is. They would lose their lives to protect him.’”

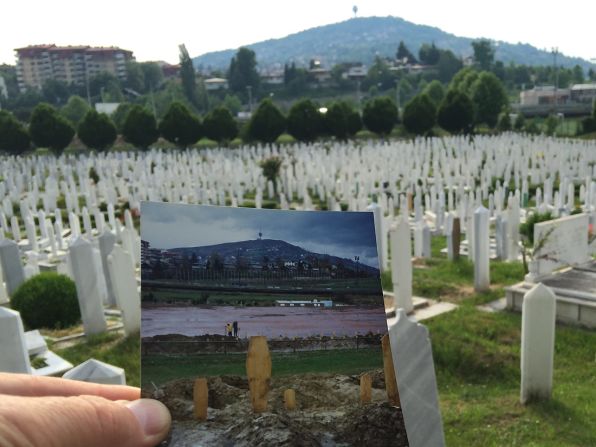

Sarajevo: Then and now

Despite years on the run, Karadzicwrote a book of poetry, “Miraculous Chronicles of the Night”– 1,200 copies of which sold out at the 2004 Belgrade International Book Fair.

After his arrest was announced, Serb officials revealed the final chapter of his life on the run had seen Karadzic reprise his medical role, working in a clinic in Belgrade under a false identity and heavily disguised by a white beard, long hair and spectacles.