Story highlights

Nearly 200 people died in three horrific stadium tragedies in the 1980s

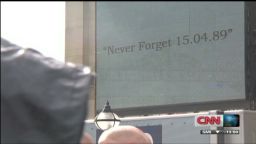

Some say that the one at Heysel in 1985 has been largely forgotten

Thirty-nine fans died at the Belgian stadium before European Cup final

Juventus insist the club still honors the relatives of Heysel victims

For Antonio Conti, time stopped on the evening of May 29, 1985.

He had taken his Juventus-supporting daughter Giusy to watch the Italian club play English team Liverpool in the 1985 European Cup final in Brussels at the Heysel Stadium.

It should have been a time for celebration. Father and daughter watching the most prestigious club game in European football in the traditional climax to the season.

Instead, Conti’s memories of Heysel are of mayhem and death.

“It was 19:25 CET when everything happened,” Conti told CNN. “When I woke up half an hour later I was among dead people, and at that moment I remembered where I was.

“I looked for my daughter until I saw a shoe under a blanket and I understood that she was dead.”

For the modern European football fan used to watching matches in bright, shiny all-seater stadiums, it is almost impossible to imagine attending a football game and dying there.

But in the space of four years in the 1980s, nearly 200 people lost their lives in three horrific European stadium tragedies. First, on May 11 1985, just over two weeks before the Heysel stampede, came a devastating fire at the Bradford City Stadium fire on May 11, and then there was a deadly crush at another English ground – Hillsborough – in 1989.

It is only in the last few months that Britain’s political and civil institutions have begun to be held to account for the reasons behind the death of 96 people during an FA Cup match at Hillsborough, which has long cast a shadow over the city of Liverpool.

Four years earlier at Heysel, Liverpool had been involved in another stadium tragedy as 39 fans – 32 from Italy, four from Belgium, two from France, one from Northern Ireland, the youngest just 11 years old – were killed in a stampede before the European Cup final against Juventus.

“For me that cup will always be covered in death,” wrote Juve defender Antonio Cabrini in his autobiography “Io Antonio.” “The cup of death”.

Forgotten story

Heysel is a story of “incompetence, violence, cover-up, shame and lies,” writes Professor John Foot – the author of the authoritative history of Italian football, “Calcio.”

“It’s also a story of forgetting,” adds Foot. “Many people have an interest in not remembering what happened that night: the players, many fans, the Belgian politicians and police forces.”

Foot’s analysis is shared by Rosalina Vannini Gonnelli, who lost her husband in the tragedy and whose 18-year-old daughter was injured that night 27 years ago.

“Is there anyone who gives a damn?” questioned Gonnelli. “News has to be on the front page, then everyone forgets. My daughter will carry that with her for her whole life.

“I’m happy that sometimes there is someone who remembers the tragedy.

“Many, many years have passed. People had forgotten soon after it happened, so now there’s no way. The 39 angels will always be in the memories of their loved ones.”

Journalist Francesco Caremani was an Italian who cared, and in 2003 he wrote a book about the tragedy – “The Truths of Heysel – Chronicle of a Tragedy Foretold.”

Caremani was a friend of Otello Lorentini, who was head of the now disbanded Association for the Victims of Heysel.

Lorentini’s son Roberto was a doctor who died at Heysel. Roberto had resuscitated a boy before being crushed to death, an act that saw him posthumously awarded a civic medal for his bravery.

“Before my book nobody had listened to the victims. It was the first chance that they had had to speak about the night of the Heysel disaster, of the process and the battle for justice,” said Caremani.

When Roberto Lorentini died in 1985, his son Andrea, who is now a sports journalist, was just three.

“I’m angry and bitter because it’s impossible to die for a football match,” said Andrea. “There isn’t logic for what happened in Brussels.”

Sector Z

There are close parallels between Hillsborough and Heysel – disasters waiting to happen at two dilapidated stadiums, which hosted major games with poor ticketing arrangements and “negligent policing.”

Read: Police chief resigns amid UK soccer stadium crush questions

Heysel Stadium’s Sector Z terrace had grass poking through the crumbling concrete. Flimsy wire-netting separated the Liverpool and Juve fans while a minimal police force battled to keep control of thousands of fans. A police force whose walkie-talkies had no batteries.

“I felt a lot of anger and bitterness towards UEFA that allowed such an important match to be played in an inadequate stadium,” said Conti. “The curved sector where we were should not have been open to the public, because it wasn’t up to hosting 15,000 people.

“In that sector there were hooligans as well and the police weren’t able to keep order.”

Then came the charge of the Liverpool fans.

“There are dozens of points that are usually offered to explain the context, but the context does not begin to excuse anything,” writes Liverpool fan Tony Evans, football editor of British newspaper The Times.

“No amount of context could. That stampede might have been considered standard terrace fare, a token act of territorialism and intimidation, but it led innocent fans to flee in terror.

“Some tried to climb a wall to escape. The wall crumbled. Thirty-nine people were crushed to death. The world was appalled. Turin went into mourning. Liverpool and their supporters were left with the stigma and the stain.”

With corpses lying in the stadium car park, UEFA ordered the game to go ahead for the sake of public safety. Juventus won the final 1-0 thanks to a penalty from Michel Platini, who is now president of the European governing body.

“I was at home watching the match on television, but I had the feeling that something terrible had happened to my loved ones,” said Gonnelli. ” I spent the whole night at Pisa airport waiting for them to come back.”

Platini’s celebration after scoring the penalty was widely criticized, though he justified playing the game by arguing that if it had not gone ahead, it “would have been the end of football.”

Another relative told CNN that Juventus had always wanted to put a veil over Heysel to forget this page in the club’s history and that the Serie A side’s then president Giampiero Boniperti should have handed the European Cup back.

Juventus insist that the club has never forgotten the suffering of the family victims and that the disaster’s anniversary is always religiously marked.

A commemorative monument was unveiled in the main courtyard of the club’s headquarters shortly after the disaster, and there was a dedication to the victims at the opening of Juve’s new stadium last year.

“The families of the victims are always welcome at the club, our museum and the stadium and they can come for free,” said a Juve spokeswoman.

Liverpool FC also marks the anniversary of the tragedy, with flowers placed on the memorial plaque and flags flown at half-mast, while its website features stories of remembrance.

The right punishments?

In the aftermath of Heysel, then UEFA president Jacques Georges and general secretary Hans Bangerter were threatened with imprisonment, before being given conditional discharges.

Albert Roosens, the former secretary-general of the Belgian Football Union (BFU) and Johan Mahieu – who was in charge of policing the stands at Heysel despite having never supervised a football match before – were given six-month suspended prison sentences for negligence.

“Heysel is the tragedy of the century,” said Caremani. “UEFA and Belgian institutions are the guilty ones – they chose that stadium and it was the worst stadium in Europe for a final of the European Cup.

“UEFA, the Belgian institutions, England and Italy try to forget about it. They don’t care about the victims. It is only after Heysel that UEFA took responsibility for stadium safety.”

Conti added: “The Italian state, the Italian Football Federation and Juventus took little interest in the case.”

That critique of establishment inertia might strike a chord with those relatives of the Hillsborough tragedy who have campaigned so tirelessly for the true story of their family members’ deaths to be told.

Read: Panel - Police at fault in response to deadly UK stadium football crush

In the aftermath of Heysel, 25 Liverpool fans were subsequently extradited from the United Kingdom and, after a five-month trial, 14 were found guilty of voluntary manslaughter in April 1989 – the same month of the Hillsborough disaster – with each of them serving a year in jail

English clubs were excluded from Europe for five years, with Liverpool handed an extra year’s ban.

“The anger at the hooligans of Liverpool is still very strong, unspoken, but very strong, both among the relatives of the victims – who know the history very well – and especially among the Juventus ‘ultras’ – who know it a little ‘less well,’ ” said Caremani, before adding: “but everyone knows very well UEFA and Belgian institutions’ responsibilities.”

Lasting shadow

Last month the family of victims of the Hillsborough disaster received an apology from British Prime Minister David Cameron for the long delay in giving answers to all those affected by “one of the greatest peacetime tragedies of the last century.”

Cameron’s apology and the publication of an independent panel’s report revealing serious failings by police and emergency services was a major breakthrough for the Hillsborough campaigners after their many years of battling to get to the truth.

“I feel solidarity with the Hillsborough victims – only those who experienced it can understand,’ said Gonnelli.

The truth about Hillsborough might have taken 23 years to finally seep out but in the interim, English football fans saw vast improvements to the stadia in England as a direct result of the disaster. All-seater grounds in the top leagues were enforced on the back of recommendations made in Lord Taylor’s report of 1989.

No longer would fans go to a football match in fear of their lives.

But was that the case in Italy?

Caremani’s concern is that stadium organization in Italy still remains a problem.

‘Italy has not learnt the lessons in the way England did,” he said.

“Italian hooligans are very fascinated about English hooligans. It was the model for Italy. English stadiums are really the best in the world, or most of them are.

“We have not learnt the lessons of stadium safety and organization – the Taylor report is a totem for me. But it came after Hillsborough. Why not after Heysel?”

Additional reporting by Chiara Martini