Story highlights

Rupert Murdoch took charge of his first newspaper in Australia at the age of 22

He spent the next 50 years expanding into TV, press, internet, sport, and movies

Forbes estimates the 83-year-old media mogul and his family's wealth at $14.5 billion

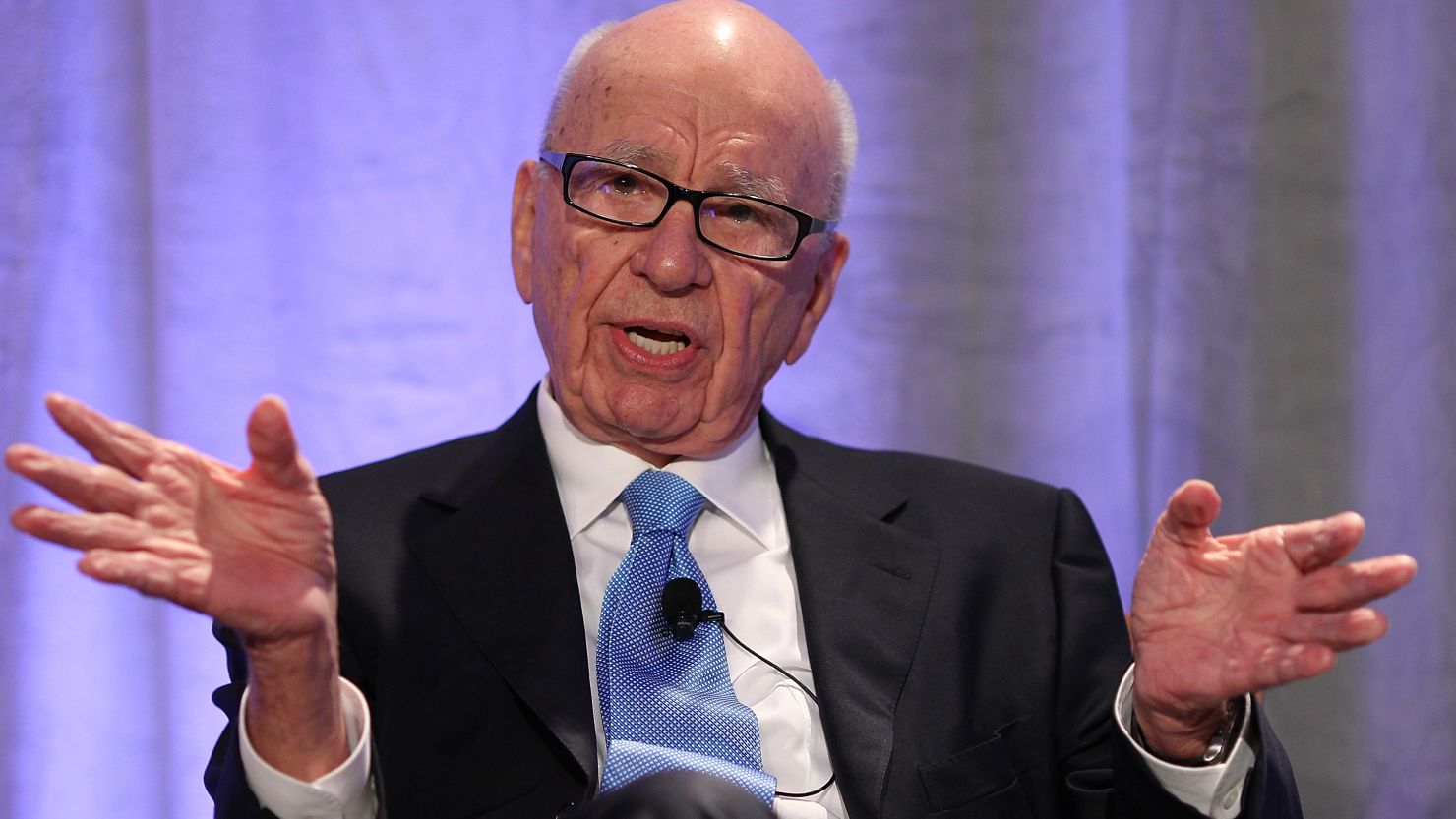

Rupert Murdoch is the last of a dying breed: An old-fashioned press baron with ink running through his veins, a hefty checkbook, and a hunger for the next big story.

Now aged 83, he has spent the past half century turning a business that began with one local Australian newspaper into a massive multimedia empire which spans the globe and includes TV, online, film and print interests.

The phone-hacking scandal forced him to close the British tabloid that was his pride and joy, News of the World, and for a time even appeared to jeopardize his global empire, valued by Forbes at $9.4 billion. It led the powerful businessman to submit himself for questioning by British politicians, where he declared: “This is the most humble day of my life.”

But Murdoch bounced back from the crisis, and he remains at the helm of his global empire. In 2013, News International, the UK subsidiary of Murdoch’s News Corp. was rebranded News UK, while News Corp. itself split into two separate entities. News Corp. is now focused on publishing while 21st Century Fox encompasses television and film assets.

This month, Forbes estimated the net worth of Murdoch and his family at $14.5 billion, adding that stocks from the two companies had boosted his worth by more than $2 billion in the past year.

The same year, Murdoch filed for divorce from his third wife, Wendi Deng.

Deng had grabbed headlines when she lunged to defend her husband from a pie-throwing intruder at a 2011 parliamentary hearing in London, earning her the sobriquet “tiger wife.” But speculation about the state of the couple’s relationship had swirled for months before Murdoch’s spokesman confirmed the divorce.

One tweet fittingly declared that Murdoch had gone “from tabloid boss to tabloid prey.”

The media mogul was kept on the edge of the limelight from October 2013, when former employees went on trial for alleged phone hacking.

The newspaper business is in Murdoch’s blood. Born in Melbourne, Australia, in 1931, he was one of four children – the only son – of a celebrated journalist and his debutante-turned-philanthropist wife.

His father, Keith Murdoch, was a reporter who exposed the horrific conditions experienced by Anzac troops fighting at Gallipoli in World War I, and went on to manage a large newspaper company.

“I was raised in a newspaper family by a father who believed that the newspaper was among the most important instruments of human freedom,” Murdoch declared in his 2008 Boyer Lectures.

His mother, Elisabeth, was inspired to devote her life to “good works” as a schoolgirl. At the time of her death in 2012, aged 103, she remained a supporter of more than 100 charities, and enjoyed an almost regal status in Australia.

Murdoch was studying at Oxford when his father died in 1952.

Mentored – like his father – by press baron Lord Beaverbrook, he learned his trade as a reporter in Birmingham, England and as a £10-a-week sub-editor at Beaverbrook’s Daily Express in London before returning home to take charge of the family business.

“I found myself a newspaper proprietor at the age of 22,” Murdoch said in 2008. “I was so young and so new to the business that when I pulled my car into the lot on my first day, the garage attendant admonished me, ‘Hey sonny, you can’t park here.’”

Despite his youth, the new boss of the Adelaide News took to the job like a duck to water, quickly getting embroiled in a newspaper war – the first of many – with local rival the Adelaide Advertiser.

“It cost a great deal,” he said. “But it taught me that with good editors and a loyal readership, you can challenge better-heeled and more established rivals – and succeed.”

He was soon looking to expand the company: After buying up other local papers across the country, in 1964, he set up Australia’s first national newspaper, The Australian, and in 1969, moved overseas to purchase his first UK paper, News of the World, shortly followed by The Sun.

The sensationalism and sex on the pages of some of his papers provoked shock and anger among his competitors on Fleet Street, and earned Murdoch a number of less than complimentary nicknames.

As Ian Hislop, editor of British satirical magazine Private Eye, told CNN: “[We have] referred to Murdoch as the Dirty Digger throughout his long career, and it’s not an accident; he does dig up dirt and then puts it in papers and sells it.”

His hunger for the latest scoops – and his willingness to pay for them – have ensured massive sales figures, but have also caused controversy over the years, from Christine Keeler’s kiss-and-tell over the Profumo scandal, to the “Hitler Diaries” (later revealed to be fakes) to O.J. Simpson’s “If I Did It” book.

That desire to be first with the big news has led some to question his methods – even before the phone-hacking scandal.

“He ran close to what might be considered journalistic ethics,” said Lou Colasuonno, former editor-in-chief of the New York Post, which Murdoch took over in 1976.

“I’m not saying he broke the law, I’m not saying he did anything illegal, but I am saying he’s aggressive in getting stories.”

Print unions

That aggression was evident in the mid-1980s when Murdoch, by then the owner of London’s Times and Sunday Times papers, broke the stranglehold of the unions on the country’s print industry.

After months of plotting, the media titan switched his operations from Fleet Street to Wapping, in the east end of London, and from hot metal to computerized systems overnight, forcing hundreds of printers out of work.

“He was the man who tamed the print unions so that newspapers became incredibly profitable,” said Martin Dunn, former deputy editor of the Sun and News of the World.

Those profits were plowed into Murdoch’s growing Fox network of TV and film interests in the United States, helping to create the corporate behemoth that is News Corp., which now also owns the influential Wall Street Journal, America’s largest circulation daily.

The thrice-married father-of-six Murdoch has long been at the center of a frenzied succession debate – something the current scandal only complicates. His oldest four children – daughters Prudence and Elisabeth, and sons Lachlan and James – all have a say in the running of the company.

His youngest daughters Grace (born 2001) and Chloe (born 2003), with Wendi Deng, are both said to have a financial share in News Corp.

Famously hands-on, Murdoch has never shied away from getting stuck in – whether tracking down a story, or dictating the political direction of his papers.

“If I see things in the paper which I think are incorrect, I’ll certainly point it out and say ‘so-and-so made a mistake here,’ or ‘this wasn’t as good a report as was in the opposition newspapers,’” he told the makers of BBC documentary “Who’s Afraid of Rupert Murdoch?” in 1981. “I … have the right to insist on excellence.”

On the same program, Robert Spitzler, former managing editor of the New York Post said Murdoch’s role went beyond commenting and suggesting.

“Rupert wrote headlines, Rupert shaped stories, Rupert dictated the leads of stories,” he said. “Rupert was everywhere.”

In a 1968 television interview, Murdoch admitted that he enjoyed the power his position gave him, but – in remarks that now seem more relevant than ever – insisted: “We have more responsibility than power, I think.

“A newspaper can create great controversies, stir up arguments within the community … can throw light on injustices, just as it can do the opposite, can hide things and be a great power for evil.”

But even those who may be considered his enemies recognize Murdoch’s business acumen.

“He’s a dealmaker, he’s a brilliant businessman,” Michael White, of the UK’s Guardian newspaper, which broke the hacking story, told CNN. “He’s a great strategic mind.”