Editor’s Note: James Montague is the author of When Friday Comes: Football, War and Revolution In The Middle East, a look at Middle East cultures and politics through the prism of football. Follow him on Twitter.

Story highlights

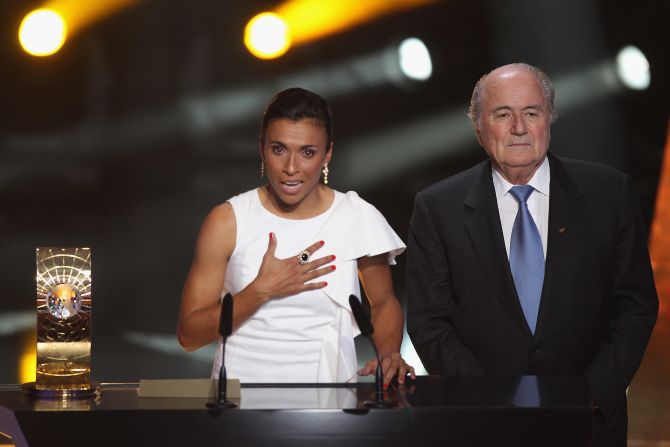

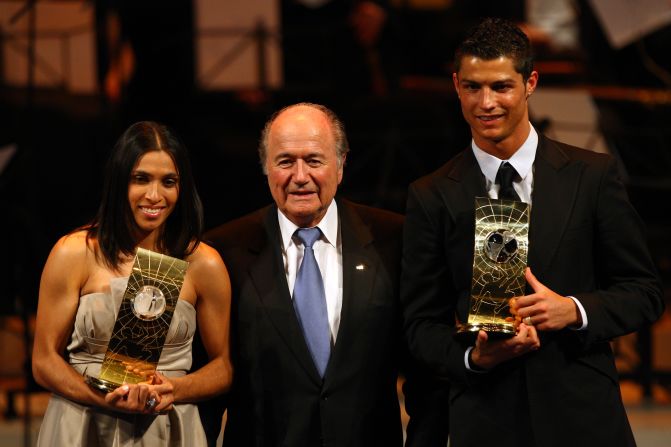

Sepp Blatter has been criticized for saying players cannot "run away" from racism

FIFA president's comments came after Kevin-Prince Boateng walked off pitch in protest

Ghana international was playing for AC Milan in a friendly against fourth division Pro Patria

Blatter has been president of world football's governing body since 1998

There can’t be many people whose image has sat side by side on a front page with Colonel Gaddafi, the now expired former dictator of Libya. But Sepp Blatter, the president of soccer’s governing body FIFA, is one of the few to hold this dubious honor.

It was June 2011, and The Sun – a British tabloid newspaper owned by Rupert Murdoch and known for its cheeky, salacious front pages – ran one of its most memorable headlines.

“Despot the Difference,” it screamed above a picture of Blatter and Gaddafi. “Two deluded dictators continued to cling on to power yesterday as their corrupt regimes crumbled around them.”

The ire directed at Gaddafi was obvious. But Blatter? Soccer’s administrator in chief had become one of the most hated men in Britain.

Blog: Time for football to tackle racism epidemic?

A series of corruption scandals within FIFA, his botched re-election campaign – where his only opponent was barred from standing after another corruption scandal – and the failure of England’s bid to host the 2018 World Cup to attract any interest in FIFA’s corridors of power (despite having the best technical report) led to an outpouring of incredulity. Blatter was deemed arrogant and elusive. He became public enemy number two, after Gaddafi.

Just over 18 months on and Blatter has fared slightly better than Gaddafi. But only just. This weekend he was vilified again for refusing to back the principle of AC Milan walking off the pitch when one of the Italian club’s black players was racially abused by fans.

It was seized as another example of Blatter’s buffoonery and came after comments he made in a 2011 interview with CNN when he seemed to suggest there was no problem with racism in soccer, at least on the pitch.

Read: Boateng makes racism vow

But is this foolishness, myopia or inelegance? I would say the latter of the three. His comments on the AC Milan incident were broadly correct. Whilst Kevin Prince Boateng should be applauded for his “Rosa Parks” moment, enshrining it in law would be highly problematic.

As James Lawton in the British newspaper The Independent wrote this week in a piece criticizing UEFA for its weakness on tackling racism: “Boateng has issued a significant threat, not just of uncomplicated outrage by black players, but situations which would create incentives for all kinds of connivance in the abandonment of vital matches in which one side had taken what looked like an impregnable advantage.”

That soccer’s governing bodies contributed to the situation by handing out paltry fines for previous transgressions is true too.

Sure, FIFA is not without its problems, but the sound bites tend to obscure a much wider, more important truth: Blatter’s largely positive influence on the game, especially in the developing world.

Read: Fan group calls on club not to sign black players

Whilst he is parodied as an out of touch buffoon haphazardly directing affairs from FIFA’s “Death Star” in Zurich, he has arguably done more in the modern era to spread the game globally than anyone else.

This year I interviewed Blatter twice. On both occasions he talked about soccer being more than just a game. That it was also an agent of social change. His first act when elected president in 1998 was to fly into the Gaza Strip and welcome Palestine to the soccer family.

It allowed the Palestinians to organize their own league, push for movement restrictions in the West Bank to be lifted, to build their own national football stadium, start a women’s professional league and, in 2011, host their very first World Cup qualifier against Afghanistan.

Sure, the Afghan government were not happy, but the team traveled and played in the West Bank, the first time a team from Afghanistan had done so. It was defacto recognition of both sides of this seemingly intractable conflict.

FIFA became one of a tiny handful of international organizations to recognize the existence of Palestine, a full four years before a U.N. vote almost, but not quite, got to the same point.

The Palestinians have cleverly used soccer as a way of both flying their flag and as a dry run for building and maintaining important civic institutions. Blatter should take credit for kickstarting that movement.

The wider point here is that Blatter’s tenure as FIFA president has been internationalist in tooth and claw. Under his watch the World Cup was hosted in Asia for the first time in 2002. It is a region that, in 50 years’ time, will undoubtedly be the new power center of the world game.

Blatter championed Africa’s first ever World Cup, in South Africa in 2010, a remarkable vote of confidence in a country barely two decades out of apartheid.

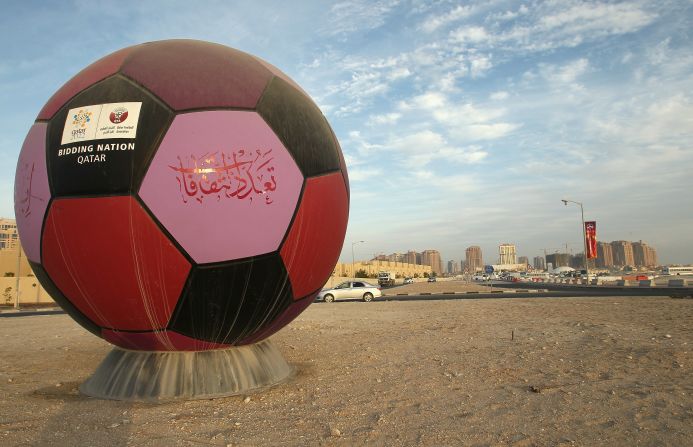

And, most controversially, Russia and then the Middle East will host their first World Cups in 2018 and 2022 respectively. No one should have been surprised by either move. Both regions are booming and have a deep love of the game. FIFA under Blatter has been aggressively expansionist and hosting a World Cup in England or even the U.S. would have added little new.

Soccer is, now more than ever, a global game and deserves to be shared across the world. Europe may now be the most successful region both in terms of money and success on the pitch but the balance of power is shifting, to South America, Asia, the Middle East and the new Europe.

Blatter recognized that shift and helped to drive it. Given that context it would be absurd to now think that the 76-year-old was someone unconcerned with the issues of racism.

Now there are a new set of pressing challenges. The rise in racism needs to be tackled with financial penalties so stiff that clubs would have no choice but to take the issue seriously.

Greater transparency within FIFA’s decision making and finances need to be addressed. The corruption watchdog Transparency International cut its ties with FIFA in 2011 when two of its recommendations – that the investigator charged with overseeing FIFA would be compromised if he was paid by FIFA and that he should be allowed to investigate old corruption scandals – were dropped.

The stain of corruption emanating from countries with poor records in transparency and openness is another issue. Why not publish the salaries and expenses of FIFA’s leading members to combat that?

But, when his tenure is up, the same question will be asked. Will Blatter leave the game in a better place than he found it? The game has been spread further and deeper than ever before. There is much that still needs reforming in FIFA. But in Africa, Asia and the Middle East he’ll be rightly feted for seriously taking the game to the world, no matter what the headline writers think.