Story highlights

Democratic Republic of Congo defender Chancel Mbemba Mangulu has "four birthdays"

Mbemba case raises issue of age fabrication in football

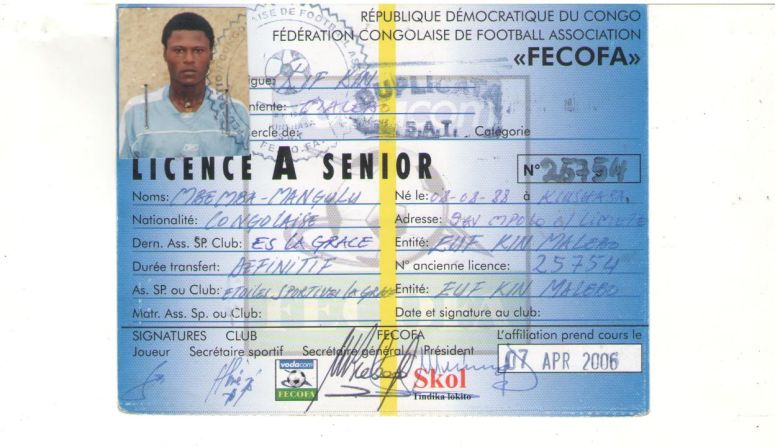

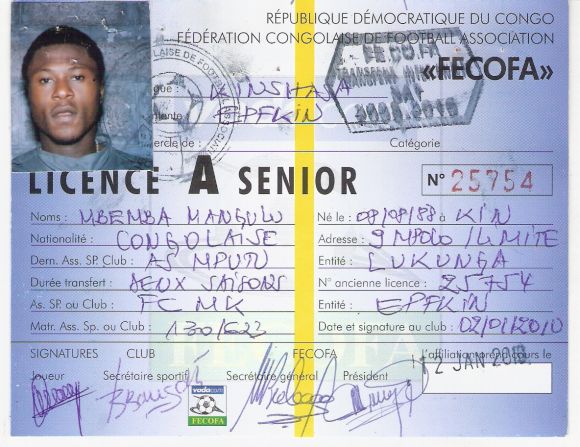

Defender's birth date registered at Congolese E.S. La Grace and Mputu as August 8, 1988, according to documents given to CNN

Now an Anderlecht player, Mbemba's date of birth is listed as August 8, 1994

Everyone has a birthday. A joyful day for receiving presents from family and friends, for blowing out candles on a cake as you celebrate your arrival on this earth.

Some people even have two, such as Britain’s Queen Elizabeth II – one to mark the date of her birth, and one to celebrate the anniversary of her coronation.

But soccer player Chancel Mbemba Mangulu can top that. He appears to have four “birthdays” – and it has caused him a lot of problems. So much so that football’s world governing body FIFA has now started an investigation.

“We are currently analysing all the documents at our disposal and investigations against the relevant entities are on-going,” FIFA told CNN on Thursday. “In view of this, we cannot comment any further.”

Mbemba was part of the Democratic Republic of Congo’s (DRC) squad for the Africa Cup of Nations – considered one of the toughest tournaments in world soccer – but, before that, confusion over his date of birth almost put an end to his dreams of a career with a top European club.

Mbemba was registered by his two first Congolese clubs as being born in 1988, according to documents obtained by CNN. Yet for a Cup of Nations qualifier in June 2011, his year of birth was listed as November 30, 1991.

Meanwhile, the birth date recorded by his Belgian club Anderlecht is August 8, 1994.

Just to complicate matters, Mbemba himself, thinks he was born in 1990.

Father Time

The movement of African players to Europe is long established. As many as 137 European clubs from 26 different UEFA member associations have released players for the Cup of Nations. Out of the 368 footballers competing in the tournament, over 50% play in European leagues.

European clubs generally regard African players as athletically and technically gifted. Arguably just as importantly they are relatively cheap to buy, with the added potential that clubs can make a large profit if they are sold in the future.

For the players, the idea of becoming of a professional footballer in Europe holds the promise of a better life for themselves abroad and their families back home.

But the issue of age is no trivial matter in football’s high-stakes world.

Key tournaments involving national teams, such as the Olympics and the Under-20 and Under-17 World Cups, have age limits for participating players. An over-age player brings the advantage of having increased physical development as well as more tactical training and experience at a high level on the pitch.

In professional leagues, as a player ages, Father Time becomes the enemy. A player who is older is perceived as closer to being past his prime – and clubs tend to be less willing to invest in him by offering them a lucrative contract.

Bureaucratic nightmare

Born in the Congolese capital of Kinshasha, Mbemba had more reasons than most to try and play in Europe.

Despite the nation’s wealth in natural resources, the country’s citizens are among the poorest in the world, and it has seen more than its fair share of violence over the decades. Civil wars – most recently in the 1990s through 2003 – have left millions dead across the country and displaced entire generations.

“I want to go there,” Mbemba kept repeating as he dreamed of following in the footsteps in one of Kinshasa’s most famous sons – former Real Madrid, Chelsea and Paris Saint-Germain midfielder Claude Makelele. “Our family was very, very poor,” he added in an April interview.

Recent attempts to contact Mbemba to shed light on his unusual story have gone unanswered.

While Mbemba’s dream has become something of a bureaucratic nightmare, his story also highlights the continuing issue of age fabrication in football.

In 2009, the Confederation of African Football (CAF) was embarrassed in the run-up to the Under-17 World Cup in Nigeria when FIFA introduced MRI scans to ensure teams were not fielding overage players.

Wary of the tests, Africa’s competitors ran their own tests to discover a handful of The Gambia’s African championship-winning side were overage, while Nigeria was forced to drop over a dozen players from its proposed squad.

‘We needed him’

Age fabrication allows nations to field stronger teams in youth tournaments. The age of player is also important for the buying and selling club as it has implications for their salary and future sell-on value.

“Most of the age cheating is intentional and aimed at securing victories in international youth competitions, or overseas contracts, especially in Europe,” African historian Peter Alegi, author of “African Soccerscapes: How a Continent Changed the World’s Game,” told CNN.

“Almost everyone up and down the commodity chain is involved – from coaches and recruiters to family and the players themselves.”

A technically gifted defender, Mbemba played for three clubs in the Congo beginning in 2006,with his birth date registered at E.S. La Grace and Mputu as August 8, 1988 – according to copies of official Congolese player photocards given to CNN – before he joined MK étanchéité.

The documents showing Mbemba’s various ages were provided by the Brazilian agent Paulo Teixeira, who says he was called in by E.S. La Grace to obtain money they claimed was owed to them by Anderlecht for training the player in his formative years.

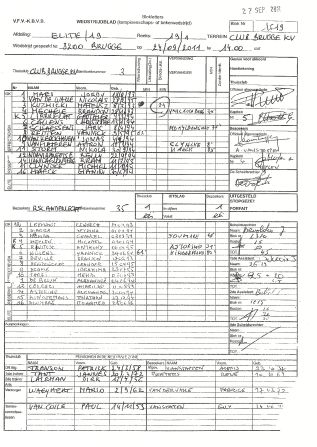

In attempting to verify these documents – from FIFA, the various federations and clubs involved – only the world governing body and the Belgian FA responded directly to CNN’s request to confirm their authenticity, while a professional Belgian referee confirmed that the Anderlecht team sheet was the type of paperwork used in Belgian football.

“It goes by itself that it is impossible for the Belgian FA to control manually whether every player taking part in a game organized by our federation is also a member of our federation,” said the Belgian FA in a statement.

“Weekly, the Belgian FA organizes more than 10,000 games all over the country (300,000 every year) and so far, most of the official match sheets are not digitalized.

Mbemba’s talent ensured he quickly came to the attention of the Congo national coaches, though, with his birth date listed as 1988, Mbemba would have been ineligible for the 2012 Olympic Games if the DRC squad were to make it through the qualifying rounds.

That, according to an official of Congo’s football federation, prompted authorities to turn the clock forward.

“We needed him, so we registered him as being born in 1991,” explained the staff member of the Fédération Congolaise de Football-Association – FECOFA – who asked not to be named because of the sensitivity of the subject.

However the testimony of another Congolese player, Mike Cestor, who plays for fifth-tier English club Woking, suggests that the Mbemba case is not a one-off.

“I was selected for an Olympic Games qualifying match with Congo’s under-23 team against Morocco,” said Cestor.

“But it was a complete mess – the organization, training and the trip itself. We were three new players who played in Europe.

“The FECOFA told us: ‘We’ll make a passeport provisoire,’ ” added Cestor, referring to the official document which is issued by a country’s football association on behalf of the players and is submitted to match officials for a game.

“Every player had a passeport provisoire – it was shocking, though, mine never arrived,” said the Woking player, whose dream is still to play for the Congo national team despite the organization of the FECOFA..

“Before the game, one lady from Morocco was checking the passports. She was angry and she screamed in French: ‘It’s a disgrace! I never saw that in all my life!’

“She knew it was false but she couldn’t do anything. Of course the dates of birth were untrue.

“The FECOFA and the staff write what they want, especially for the local players. It was comical. The FECOFA is the major source of the problems in Congolese football. Its organization is awful.”

Asked why Mbemba had been allowed to play for the Congo with various different ages, FECOFA president Constant Omari declined to address the question.

“I’m a president of a federation. I don’t know what presidents in the UK say, but here we do not comment on players’ age,” Omari told CNN. “I have strictly nothing to add.”

He hung up before any other questions could be asked.

Paperwork trail

Meanwhile, Mbemba’s prospects of securing that move to Europe gathered pace after he was spotted by Fabio Baglio, who also represents one of the DRC’s leading players Dieumerci Mbokani – also of Anderlechet – and recently voted Belgium’s player of the year.

It was thanks to Baglio’s contacts that Mbemba was granted a trial by Anderlecht in June 2011.

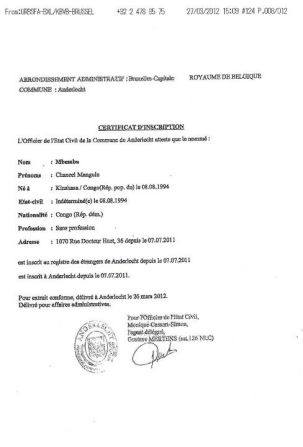

Granted a residence permit the following month, Mbemba played in official games for Anderlecht, but one key piece of information had changed.

Mbemba was now six years younger with a new date of birth – August 8, 1994. How – and by whom – that date was arrived at isn’t entirely clear.

Africa Cup of Nations

Africa Cup of Nations breakdown

Mbemba himself has continued to say in interviews that he was actually born in 1990. Regardless, with the new club and his new birth date, the paperwork trail began to catch up with him.

One of Mbemba’s former club presidents, Bernard Yuka of E.S. La Grace, decided it was time to claim a training compensation fee from Anderlecht – given that the Congo team had helped train him and was, therefore, entitled to development costs associated with nurturing him as a player.

Yuka mandated the Brazilian agent Paulo Teixeira, who has experience of working with small African and South American clubs to obtain player development payments, to help E.S. La Grace obtain the money from FIFA, which adjudicates such cases.

During a conversation between Teixeira and Yuka – the Brazilian has provided CNN with a transcript of that exchange – the E.S. La Grace president allegedly told the agent that FECOFA president Omari wanted the training compensation case dropped.

Last year Teixeira submitted the transcript to FIFA as part of a dispute case he was involved in with AC Milan and Anderlecht. And on Thursday, the world governing body confirmed it was now investigating the issues surrounding the Mbemba case.

Teixeira told Yuka he was happy to drop the mandate, but that the paperwork from Mbemba’s spells at E.S La Grace and Mputu was not going to go away.

“I knew the club had rights on the matter, so I pursued them,” said Yuka earlier this week, who also verified to CNN the conversation he had with Omari in April. Omari refused to discuss the issue when he was contacted by CNN.

Birthday present

At the start of 2012, Mbemba’s case developed a Kafkaesque twist.

Despite the fact that he had made his debut for Anderlecht’s Under-19 team in September 2011, playing against Club Brugge, it emerged that the Belgian Football Association had never registered the defender.

As a result, Mbemba was technically ineligible – according to source with direct knowledge of the situation – to play either in that match or in two others when he turned out for the Belgian powerhouse.

“At this moment the Belgian FA is working on the complete digitalization of its official match sheets which will be completed by July 1, 2013,” said the Belgian FA. “From then on, situations like this should no longer be possible.”

To further complicate matters, FIFA became involved in March 2012 – because if Mbemba in fact had been born in August 1994, he was technically a minor under the governing body’s Transfer Matching System rules.

“Please understand that the date of birth of any player noted in the Transfer Matching System (TMS) is confidential to parties involved in the transfer of that particular player,” FIFA said in a statement to CNN. “Therefore, we are unable to provide it to you.

“Generally speaking, we have to highlight that a falsified passport is a legal offense which has to be followed by legal authorities. TMS is a tool which provides all parties that are involved in a transfer with all the details they need to know about the player, and helps to bring transparency into a transfer.”

Opacity

With confusion growing around Mbemba’s status, Anderlecht sent him back to Kinshasa.

“Taking into account the opacity of the case and the legal consequences that may arise, Anderlecht has decided not to offer an employment contract to Mbemba,” said the club’s general manager Herman van Holsbeeck in a letter to FIFA, which was part of the documentation given to CNN.

When asked to provide clarity about the irregularities in Mbemba’s case, Anderlecht requested time to prepare a response, before communication and media manager David Steegen announced that the club would have no comment on the subject. The agent Baglio and Entacheite president Max’ Moxey also also declined to return CNN’s calls to shed light on the Mbemba affair,

Mbemba’s return to Africa was tough for him to take.

“I was born in 1990,” said the defender. While in an interview with the Sharkfoot website in April 2012, Mbemba said: “I don’t understand. Fabio Baglio told me that I had to go to Africa to come back to Anderlecht later. In May, Entacheite president Max’ (Mokey) told me I will go back.

“Anderlecht’s managing director told me I will sign a professional contract in August. The chairman of La Grace will sign a document to confirm my date of birth as 1994 and I can come back.”

In June 2012, Mbemba’s prospects brightened when the Congo national team’s French coach Claude Leroy picked him to play against the Seychelles in an Africa Cup of Nations qualifier.

Soon afterwards a Kinshasa court ruled that Mbemba was, in fact, born on August 8, 1994 and he was given the perfect present when he was handed a three-year deal with Anderlecht.

The icing on the cake for the now 18-year-old Mbemba came when he was called up for the DRC’s Africa Cup of Nations squad for the 2013 event in South Africa, though he was not used in any of the matches with Leroy’s team knocked out of the competition after drawing all three of their games.

How Mbemba’s career pans out remains to be seen. Whatever happens, he is likely to be remembered as the player who had four birthdays.

Additional reporting by Saskya Vandoorne and Alex Felton