Piers Morgan interviews the parents of Audrie Pott, the teenage girl who committed suicide after someone shared a photo of her being sexually assaulted. Watch Piers Morgan Live, tonight 9pm ET

Story highlights

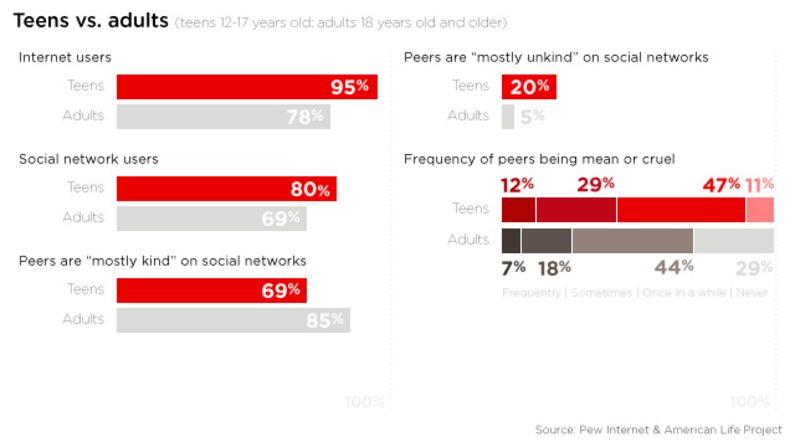

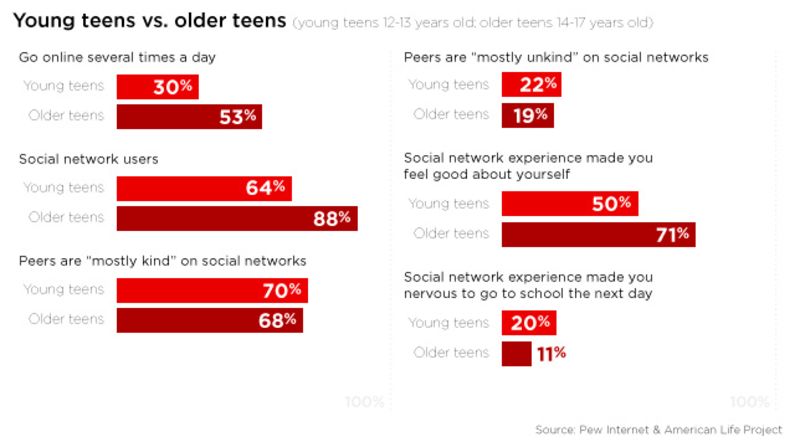

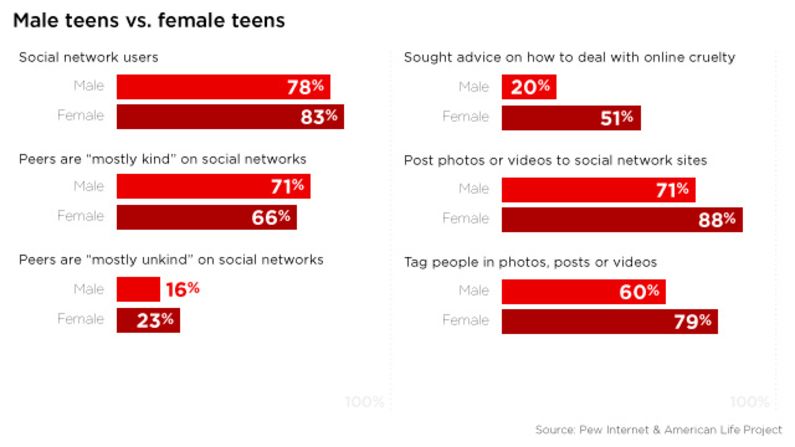

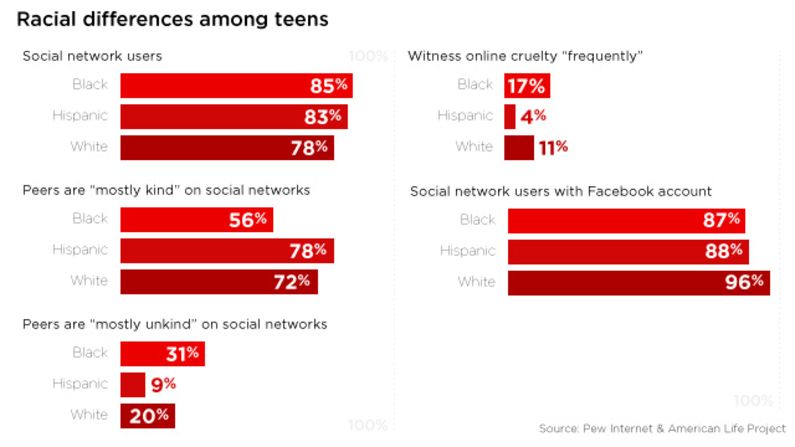

As many as 25% of teenagers have experienced cyberbullying

Among young people, it's rare that an online bully will be a total stranger

Researchers are working on apps and algorithms to detect and report bullying online

Brandon Turley didn’t have friends in sixth grade. He would often eat alone at lunch, having recently switched to his school without knowing anyone.

While browsing MySpace one day, he saw that someone from school had posted a bulletin – a message visible to multiple people – declaring that Turley was a “fag.” Students he had never even spoken with wrote on it, too, saying they agreed.

Feeling confused and upset, Turley wrote in the comments, too, asking why his classmates would say that. The response was even worse: He was told on MySpace that a group of 12 kids wanted to beat him up, that he should stop going to school and die. On his walk from his locker to the school office to report what was happening, students yelled things like “fag” and “fatty.”

“It was just crazy, and such a shock to my self-esteem that people didn’t like me without even knowing me,” said Turley, now 18 and a senior in high school in Oregon. “I didn’t understand how that could be.”

A pervasive problem

As many as 25% of teenagers have experienced cyberbullying at some point, said Justin W. Patchin, who studies the phenomenon at the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire. He and colleagues have conducted formal surveys of 15,000 middle and high school students throughout the United States, and found that about 10% of teens have been victims of cyberbullying in the last 30 days.

Online bullying has a lot in common with bullying in school: Both behaviors include harassment, humiliation, teasing and aggression, Patchin said. Cyberbullying presents unique challenges in the sense that the perpetrator can attempt to be anonymous, and attacks can happen at any time of day or night.

There’s still more bullying that happens at school than online, however, Patchin said. And among young people, it’s rare that an online bully will be a total stranger.

“In our research, about 85% of the time, the target knows who the bully is, and it’s usually somebody from their social circle,” Patchin said.

Patchin’s research has also found that, while cyberbullying is in some sense easier to perpetrate, the kids who bully online also tend to bully at school.

“Technology isn’t necessarily creating a whole new class of bullies,” he said.

Father finds purpose after son’s suicide

Long-lasting consequences

The conversations that need to be happening around cyberbullying extend beyond schools, said Thomas J. Holt, associate professor of criminal justice at Michigan State University.

“How do we extend or find a way to develop policies that have a true impact on the way that kids are communicating with one another, given that you could be bullied at home, from 4 p.m. until the next morning, what kind of impact is that going to have on the child in terms of their development and mental health?” he said.

Holt recently published a study in the International Criminal Justice Review using data collected in Singapore by his colleague Esther Ng. The researchers found that 27% of students who experienced bullying online, and 28% who were victims of bullying by phone text messaging, thought about skipping school or skipped it. That’s compared to 22% who experienced physical bullying.

Those who said they were cyberbullied were also most likely to say they had considered suicide – 28%, compared to 22% who were physically bullied and 26% who received bullying text messages.

Although there may be cultural differences between students in Singapore and the United States, the data on the subject of bullying seems to be similar between the two countries, Holt said.

A recent study in the journal JAMA Psychiatry suggests that both victims and perpetrators of bullying can feel long-lasting psychological effects. Bullying victims showed greater likelihood of agoraphobia, where people don’t feel safe in public places, along with generalized anxiety and panic disorder.

Tips for parents on bullying

Tips for parents

People who were both victims and bullies were at higher risk for young adult depression, panic disorder, agoraphobia among females, and the likelihood of suicide among males. Those who were only bullies showed a risk of antisocial personality disorder.

Reporting cyberbullying

Since everything we do online has a digital footprint, it is possible to trace anonymous sources of bullying on the Internet, he said. Patchin noted that tangible evidence of cyberbullying may be more clear-cut than “your word against mine” situations of traditional bullying.

Patchin advises that kids who are being cyberbullied keep the evidence, whether it’s an e-mail or Facebook post, so that they can show it to adults they trust. Historically, there have been some issues with schools not disciplining if bullying didn’t strictly happen at school, but today, most educators realize that they have the responsibility and authority to intervene, Patchin said.

Mother feared bullying would kill her son

Adults can experience cyberbullying also, although there’s less of a structure in place to stop it. Their recourse is basically to hire a lawyer and proceed through the courts, Patchin said.

Even in school, though, solutions are not always clear.

Turley’s mother called the school on his behalf, but the students involved only got a talking-to as punishment. Cyberbullying wasn’t considered school-related behavior, at least at that time, he said.

“I was just so afraid of people,” says Turley, explaining why he went to different middle schools each year in sixth, seventh and eighth grade. He stayed quiet through most of it, barely speaking to other students.

Fighting back by speaking out

Turley started slowly merging back into “peopleness” in eighth grade when he started putting video diaries on YouTube. Soon, other students were asking him to help them film school project videos, track meets and other video projects.

In high school, Turley discovered an organization called WeStopHate.org, a nonprofit organization devoted to helping people who have been bullied and allow them a safe space to share their stories.

Emily-Anne Rigal, the founder of the organization, experienced bullying in elementary school, getting picked on for her weight. Although she and Turley lived on opposite sides of the country, they became friends online, united by their passion for stopping bullying.

Share your story about child bullying with CNN iReport

WeStopHate.org has achieved a wide reach. Rigal has received all sorts of honors for her efforts, from the Presidential Volunteer Service Award to a TeenNick HALO Award presented by Lady Gaga.

Turley designed the WeStopHate.org website and most of its graphics, and is actively involved in the organization. In additional to Rigal, he has many other friends in different states whom he’s met over the Internet.

“I got cyberbullied, and I feel like, with that, it made me think, like, well, there has to be somebody on the Internet who doesn’t hate me,” he said. “That kind of just made me search more.”

Parental controls

Ashley Berry, 13, of Littleton, Colorado, has also experienced unpleasantness with peers online. When she was 11, a classmate of hers took photos of Ashley and created an entire Facebook page about her, but denied doing it when Ashley confronted the student whom she suspected.

“It had things like where I went to school, and where my family was from and my birthday, and there were no security settings at all, so it was pretty scary,” she said.

The page itself didn’t do any harm or say mean things, Ashley said. But her mother, Anna Berry, was concerned about the breach of privacy, and viewed it in the context of what else was happening to her daughter in school: Friends were uninviting her to birthday parties and leaving her at the lunch table.

“You would see a girl who should be on top of the world coming home and just closing herself into her bedroom,” Berry said.

Berry had to get police involved to have the Facebook page taken down. For seventh grade, her current year, Ashley entered a different middle school than the one her previous school naturally fed into. She says she’s a lot happier now, and does media interviews speaking out against bullying.

These days, Berry has strict rules for her daughter’s online behavior. She knows Ashley’s passwords, and she’s connected with her daughter on every social network that the teen has joined (except Instagram, but Ashley has an aunt there). Ashley won’t accept “friend” requests from anyone she doesn’t know.

Technical solutions to technical problems

Parents, extended relatives, Internet service providers and technology providers can all be incorporated in thinking about how children use technology, Holt said.

Apps that control how much time children spend online, and other easy-to-use parental control devices, may help, Holt said. There could also be apps to enable parents to better protect their children from certain content and help them report bullying.

Scientists at Massachusetts Institute of Technology are working on an even more automated solution. They want to set up a system that would give bullying victims coping strategies, encourage potential bullies to stop and think before posting something offensive, and allow onlookers to defend victims, said Henry Lieberman.

Lieberman’s students Birago Jones and Karthik Dinakar are working on an algorithm that would automatically detect bullying language. The research group has broken down the sorts of offensive statements that commonly get made, grouping them into categories such as racial/ethnic slurs, intelligence insults, sexuality accusations and social acceptance/rejection.

While it’s not all of the potential bullying statements that could be made online, MIT Media Lab scientists have a knowledge base of about 1 million statements. They’ve thought about how some sentences, such as “you look great in lipstick and a dress,” can become offensive if delivered to males specifically.

The idea is that if someone tries to post an offensive statement, the potential bully would receive a message such as “Are you sure you want to send this?” and some educational material about bullying may pop up. Lieberman does not want to automatically ban people, however.

“If they reflect on their behavior, and they read about the experience of others, many kids will talk themselves out of it,” he said.

Lieberman and colleagues are using their machine learning techniques on the MTV-partnered website “A Thin Line,” where anyone can write in their stories of cyberbullying, read about different forms of online disrespect, and find resources for getting help. The researchers’ algorithm tries to detect the theme or topic of each story, and match it to other similar stories. They’re finding that the top theme is sexting, Lieberman said.

“We’re trying to find social network sites that want to partner with us, so we can get more of this stuff out into the real world,” Lieberman said.

Turley and Rigal, who is now a freshman at Columbia University, are currently promoting the idea of having a “bully button” on Facebook so that people can formally report cyberbullying to the social network and have bullies suspended for a given period of time. They haven’t gotten a response yet, but they’re hopeful that it will take off.

In the meantime, Turley is feeling a lot safer in school than he used to.

“Times have changed definitely, where people are becoming slowly more aware,” he said. “At my school, at least, I’m seeing a lot less bullying and a more acceptance overall. People just stick to their own.”