Editor’s Note: Open Court is CNN’s monthly tennis show. Click here for screening times and follow on Twitter @cnnopencourt

Story highlights

It is almost a decade since an American man won a grand slam tennis title

Andy Roddick, now retired, was the last at the 2003 U.S. Open in New York

Veteran coach Nick Bollettieri claims tennis cannot compete for young U.S. athletes

He says gridiron, baseball and basketball are more attractive to parents

The future seemed so bright. When 2003 came to a close, Andy Roddick was the youngest American male to end the year as the world’s No. 1 tennis player.

Aged 21, he had just won his first grand slam title at the U.S. Open, following in the footsteps of illustrious compatriots such as Pete Sampras, Andre Agassi, John McEnroe and Jimmy Connors.

But then the drought – another decade on, the United States is still waiting for its next male grand slam winner.

So what’s gone wrong? A nation that dominated tennis from the mid-1970s is struggling to repeat those past glories – and there is no quick solution in sight.

“I think the best athletes in other countries are playing tennis sooner than they are here,” U.S. tennis great John McEnroe told CNN’s Open Court.

“We’ve got to grab some kids that are playing American football or basketball, for example, we’ve got to make it more accessible, affordable.”

But that’s not as easy as it may sound, especially when parents of talented kids do the maths.

Tennis has strong participation numbers among American school kids, but that drops off once they get to high-school age as the costs of playing skyrocket compared to subsidized sports such as gridiron, basketball and baseball.

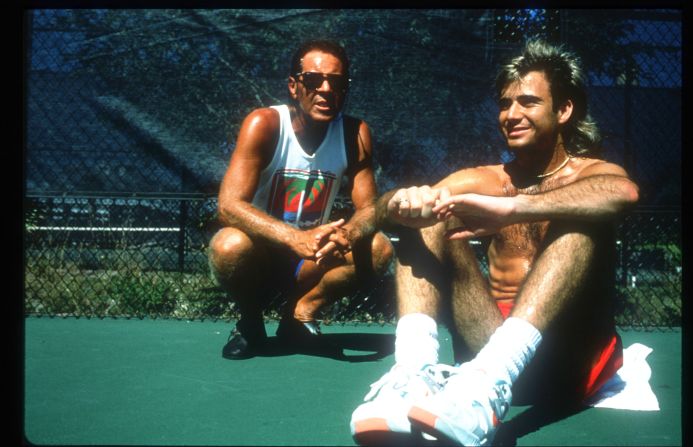

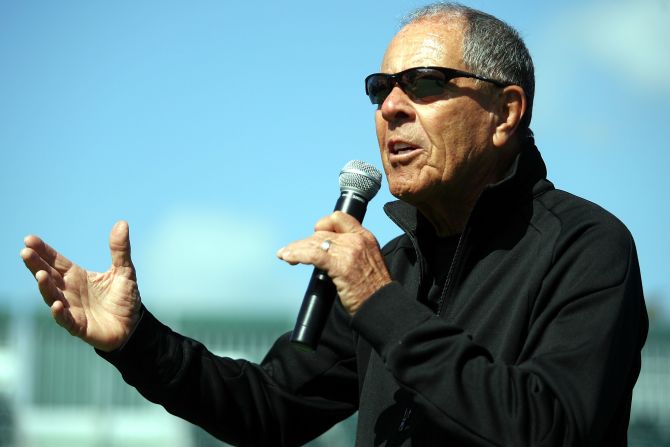

“In junior high school, the school pays for travel expenses when they go for games. When the season is over, they pay for the expenses. Tennis you pay your own,” says renowned coach Nick Bollettieri, whose academy (now owned by IMG) was the breeding ground for top U.S. men’s talents such as Agassi, Sampras and Jim Courier.

‘Show me the money’

Potential tennis stars are also being offered higher average pay by rival U.S. sports.

Bollettieri’s research has indicated that, to break even on the men’s ATP World Tour, you need to be ranked at least 163rd.

He says an NFL player of equivalent status earns $1.4 million a year – and that’s without endorsements.

“When a parent looks at the financial side and sees those two figures, they say, ‘Wow, and it doesn’t cost us a dime,’ ” added Bollettieri.

“If those same parents are struggling to make a living and they look in the paper and see $25 million for a four-year contract in baseball, $80 million for LeBron James … they look at that and the programs that develop these people, it doesn’t cost them anything.”

Read: How Novak Djokovic rose to the top

It is often argued that poverty helps breed sports stars because athletes are more determined than their wealthier peers, but seven-time grand slam champion McEnroe is unconvinced by that argument.

“Some of the guys come from tough situations who want it more – then again, if you look at some guy from Mallorca named Nadal who presumably lives in a pretty decent situation, and some guy by the name of Federer came out of Switzerland and his parents were reasonably well off,” the 54-year-old said.

Since Roddick’s New York breakthrough, Rafael Nadal, Roger Federer, Novak Djokovic and Andy Murray have won 34 of the 37 grand slam titles.

“It’s obvious that a lot of the other countries, their players have definitely become better, there’s no question about that,” says Michael Chang, the youngest player to win the French Open, as a 17-year-old back in 1989.

“The depth of men’s tennis in particular has gotten deeper and deeper every year,” the American told Open Court.

“When you’ve got guys like Rafa, Novak and Roger playing at the level they’re playing, there’s not going to be a whole lot of winners outside of those guys and now you can put Andy Murray inside of that group as well.

Read: Chang’s ‘underhand’ tactics

“It’s been very, very difficult for American tennis to be able to follow our generation.”

Success breeds success

Bollettieri believes the success of his Florida-based academy was based on offering scholarships to the likes of Agassi, Courier and Monica Seles, which later attracted other young talent from around the world including current stars such as Maria Sharapova and the Williams sisters.

“When you get good people like that at the same place, when you get 15, 20, 30 players who are the best in America and some of the best in the world, they compete,” the 81-year-old said.

“They’re in a competition, not costing them a dime – it helped get me where I am. You’ve got to have it very attractive for a young boy or girl of 11, 12, 13 years old to play tennis opposed to other sports if it looks like they’re a hell of an athlete.”

Roddick retired during last year’s U.S. Open, on his 30th birthday, and now John Isner is America’s No. 1 player.

A towering 6 foot 9 inches, he could have been a basketball player but stuck with tennis and kept playing through four years at the University of Georgia before turning professional. It’s an unusual path, as most top players join the pro ranks in their teens.

Read: Hungry Federer eyes grand slam titles in 2013

Ranked 15th in the world after reaching a career-high ninth last March, he has never gone past the quarterfinals of a grand slam. Arguably his major claim to fame is playing in the longest match of all time at Wimbledon in 2010, though he has beaten Federer and Djokovic.

“I would love to go further than that (quarterfinals) and I know my fellow American players would love to as well,” Isner told Open Court at this month’s San Jose Open, which is folding after 125 years of existence at various Californian venues.

Opportunities for young American players are reducing, with the second-oldest tennis tournament in the U.S. relocating to Brazil, while the license for the Los Angeles Open – which began in 1927 – was sold to a Colombian group last year.

“Ten years, it is a long time, but I don’t think American tennis is as bad as people portray it to be,” Isner said.

“In the ’70s, ‘80s, ‘90s, I think American tennis fans were a bit spoiled with all these great players. The game today is very, very tough. It’s very international.

“You see players in Europe that are just so strong and so physical and these guys are really dominating the game, especially the players that come from Spain.”

Size matters

Bollettieri believes Isner will struggle to win a grand slam, not because a lack of ability but because of his size – though Juan Martin del Potro, three inches shorter, won the 2009 U.S. Open.

“John has a lot of the tools, but the bigger you are you have to have footwork as well. The downfall of John today is footwork, mobility,” Bollettieri said.

He is wary of predicting a future male U.S. champion, but is encouraged by some of the young talent emerging.

Bollettieri points to Christian Harrison, the 18-year-old younger brother of world No. 76 Ryan – who at just 20 has already represented his country in Davis Cup and passed $1 million in on-court earnings.

“Today the game depends on strength, mobility and then talent. You’ve got to have strength and speed, you’ve to have at least two weapons, you’ll never make it with just one,” said Bollettieri, who also has high hopes for 15-year-old Michael Mmoh – who he calls a “big boy.”

Read: McEnroe – ‘Attila the Hun’ of tennis

If size is becoming increasingly important – players are much taller and stronger – that means tennis has to fight to keep its prospects from joining more physical sports to which they would also be suited.

“It’d have been tough to have steered Kobe Bryant or LeBron James into tennis because they were such good athletes … and the scholarships – Bryant went from high school directly to the pros,” Bollettieri said.

“It’s not that a smaller person can’t make it, but it’s more difficult today.”

Even though he is only 20, Ryan Harrison is coming to a make-or-break time in his fledgling career, according to U.S. sports journalist Douglas Robson.

“He really needs to make a move and I think he realizes that,” Robson told Open Court.

“He’s had some tough draws at majors but he hasn’t been past the second round of a grand slam yet, he hasn’t won an ATP Tour title, and a lot of players his age would’ve already passed those thresholds.”

High cost of developing champions

The United States Tennis Association (USTA) has been criticized in recent years for failing to produce successors to the last golden generation of male players, but Bollettieri supports the efforts of McEnroe’s younger brother Patrick, who took over as head of development in 2008.

“They certainly are doing a lot, but it’s tough to convince people when their son looks like he’s going to be a helluva football player or basketball player,” Bollettieri said.

He said the USTA could highlight the top 20-30 young players in the country, but it would then cost $3-7 million a year to develop them.

Read: Andy Murray’s five-star hotel venture

To attend one of IMG’s academy programs – Bollettieri sold his interest to the sports agency in 1987 – players will pay between $50,000-69,000 depending on age and whether they board. IMG gives out scholarships “on a limited basis” selected on academic, athletic, character and financial review.

“Pat is working his ass off getting more people playing the game, but what happens is when they get to be 13, 14 and have a lot of potential – that’s where the cost factor comes in and they have to come up with millions of dollars,” Bollettieri said.

“We’ve got more people playing now, more youngsters, but in order to get the champions … the people are blinded by what they see every day.”

Courier, who won four grand slam titles in the early 1990s and topped the world rankings at the age of 22, is also loathe to blame anyone for the lack of American men’s success.

“America has no ownership of the top ranking. It’s a free-for-all,” the U.S. Davis Cup captain told Open Court.

“Tennis is a very individual sport and I think it’d be very naive for a country to take the credit for individual players. Does America take credit for Tiger Woods? I’d say Earl Woods deserves the credit – he’s the one who really drove that.

“So in the tennis landscape, you look at the Williams sisters. Their father was a big driver, my family was a big driver, so I don’t think we can put any blame on anyone.”