Story highlights

Over 100 prints by the famous U.S. photographer on show at UK's National Maritime Museum

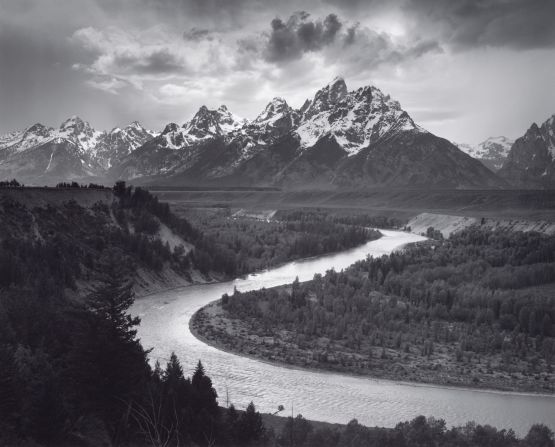

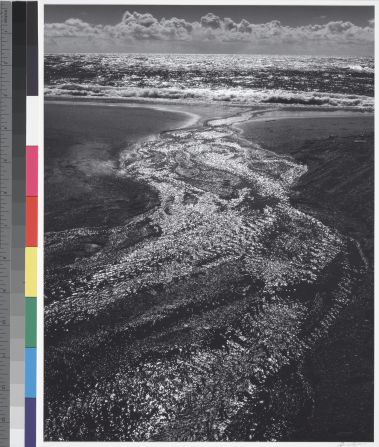

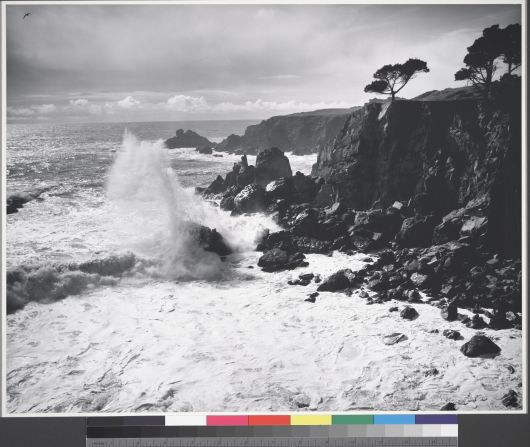

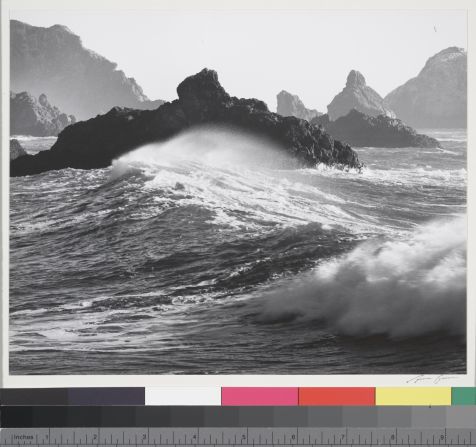

Adams' photos of American West noted for meticulous composition and image clarity

Photographer's work endlessly reprinted but exhibition hopes to re-energize engagement

Famed for his rugged, immense portraits of the American West, Ansel Adams regularly tops lists of the 20th century’s greatest nature photographers.

Adams has won countless awards, including the highest U.S. civilian honor, the Presidential Medal of Freedom. In his home country, he is one of the few photographers to have become a household name, following a 50-year career in which he captured some of the most iconic images of American National Parks and the country’s immense mountain ranges.

Today, he is rarely the subject of the intense, approving attention he once was during his lifetime – his endlessly reproduced photographs appearing to have lost the ability to enrapture and surprise viewers.

An exhibition at the UK’s National Maritime Museum in London plans to wash away viewer’s apathy.

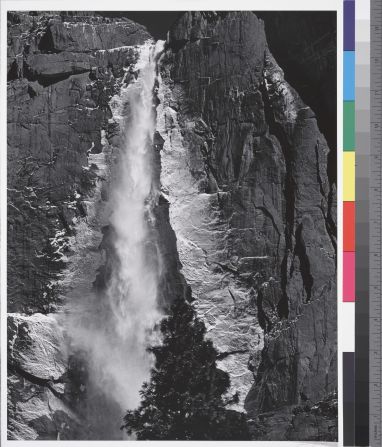

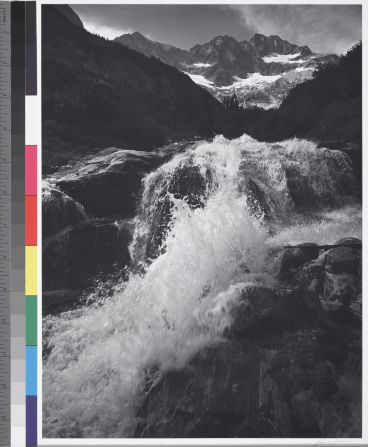

Philippa Simpson, the museum’s touring exhibitions manager, aims to re-energize engagement with Adams’ photographs by drawing attention to the life imparted into his images by the irrepressible movement of water.

The exhibition – subtitled “Photography from the Mountains to the Sea” – is showing over 100 prints from the artist.

“Adams was a coastal boy and the interest in the sea, and water more generally, permeated his entire career,” says Simpson.

“By concentrating on that as a theme for the exhibition, we felt it was a challenge in a way to the image of Ansel Adams that has been passed down as a rather conservative photographer – and we tried to draw out from the archives an alternative history of him as an artist.”

As an avid explorer of California’s Golden Gate coast, water reappears in all its forms through Adams’ body of work.

Refocusing the viewer’s attention on the running rivers, cloud, snow and ice in the images on display allowed Simpson to combine lesser-known photographs with Adams’ most celebrated works, she says.

“For us, what we really wanted to do was give a sense of the trajectory of his career – how he’s come to be known, which is by his photography of the mountains specifically – and then to say: we’re moving on from that.”

“It’s a subject that allowed (Adams) to play, which is why you get a huge variety.”

Born in a suburb of coastal San Francisco in 1902, Adams was the only child of a family who found wealth in the logging and freight trades and, soon after, lost it in the stock market panic of 1907.

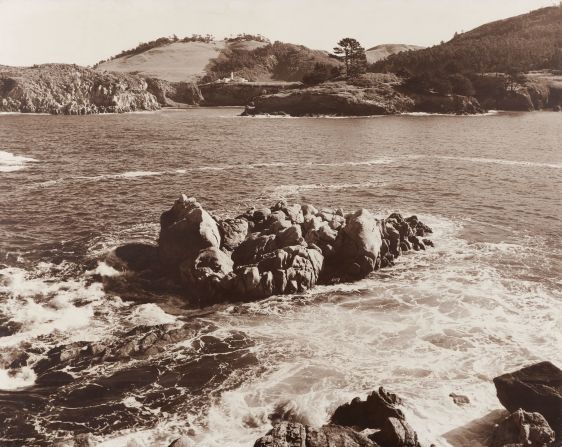

Adams experimented with a “pictorialist” style in his youth, producing some rarely-displayed photographs where he applied soft focus and hand-manipulated negatives to replicate the style of a landscape painter.

But it was his later photographs, featuring meticulous composition and striking pinpoint clarity, for which Adams, who died in 1984, became famous.

The art critic Nancy Newhall, a contemporary of Adams, described the “extreme depth of focus and extreme rendition of textures” that characterized his photographs.

She tells how he was fascinated with the camera as a tool to both stop time at a precise moment and defy the capabilities of the human eye, bringing great spans of distance into sharp focus and creating exaggeratedly high-contrast black and white frames.

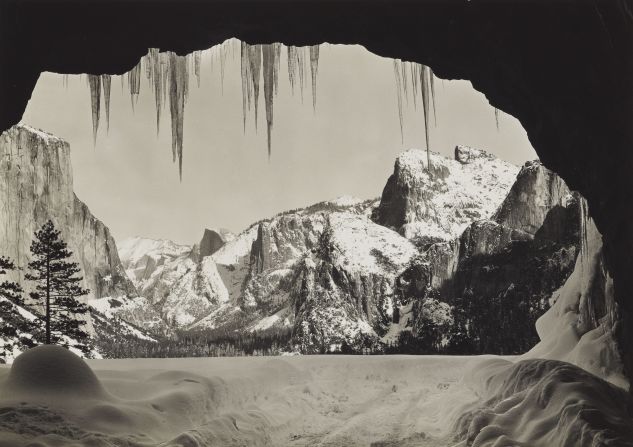

The Maritime Museum’s exhibition explores how Adams’ depiction of water changes as he developed from the pictorialism’s impressionistic style to forge the crisp modernism for which he is now know. Simpson describes how vast movements of water – frozen in time by Adams’ trademark razor-sharp shooting – bring life to one of the most well-worn images on display in the exhibition.

Adams’ “Clearing Winter Storm” is a grandiose view of a Yosemite rock face capped by snow, obscured by parting cloud and penetrated by a rushing waterfall.

“It includes water in all its forms and speaks to the ideas of a fleeting moment – the sort of ephemeral moment. It is a clearing storm, so that suggests a before and after and a sort of narrative within the picture,” Simpson says.

“It’s also a picture which I think looks very muscular and very solid and very geological. It kind of concentrates on these rocky forms, but actually it’s animated by a waterfall and by the dusting of snow and ice across the foreground.”

While many visitors will continue to greet such images with awe, the criticism – which the curator hopes to confront – is also nothing new. During the Great Depression of the 1930s, his human-free landscapes drew scorn for romanticizing a “wilderness” that was already colonized by tourism and for cropping out man’s influence.

During this time, prominent French photojournalist Henri Cartier-Bresson complained: “The world is going to pieces, and people like Adams … are photographing rocks!”

In 1952, Adams co-founded 5 Associates, a postcard printing company which today offers lithographic posters, seasonal greetings cards and month-by-month calendars bearing Adams’ images – all of which have contributed to the ubiquity of his work.

Simpson hopes a splash of water can flush out some of the best-loved qualities of his work and counter the perception of Adams as a capturer of lifeless landscapes.

“The idea of the shifting landscape is really important: that this was something which is always developing and changing, it’s not something which is static and monumental.”

The exhibition runs until April 28 2013.