Editor’s Note: Robin Oakley was political editor and columnist for The Times newspaper in London from 1986 to 1992, and the BBC’s political editor from 2000 to 2008.

Story highlights

Margaret Thatcher was the UK's first female prime minister

She had changed the philosophy of the Conservatives as well other parties

Thatcher founded popular capitalism in Britain

Her strength made her an icon to conservatives in many parts of the world

Margaret Thatcher was one of the defining personalities of the 20th century.

In diplomacy, economics, society and as a woman, she had enormous impact at home and abroad.

The test of a statesman is whether he or she changes the political weather. Thatcher, who won an unprecedented three consecutive general elections, certainly did that as UK prime minister from 1979 to 1990.

What do you think about the loss of Britain’s ‘Iron Lady’? Share your thoughts on CNN iReport

But Thatcher not only changed the philosophy of her own party, the right-leaning Conservatives, she also forced other parties to change their whole approach to politics. Since Thatcher, all British mainstream parties have been believers, more or less, in the market economy.

No other British politician during the second half of the 20th century had his or her own “ism” – but Margaret Thatcher did with “Thatcherism,” defined by some as the application of a housewife’s home budgeting to the national economy, coupled with the encouragement of home ownership and entrepreneurial capitalism.

READ: Margaret Thatcher, Britain’s first female PM, dead at 87

Her first achievement, easily forgotten now, was to go as far as she did in politics as a woman: She was, after all, the UK’s first female prime minister. It was much harder then, and the best she had hoped for when she started her political career was to become chief finance minister as Chancellor of the Exchequer.

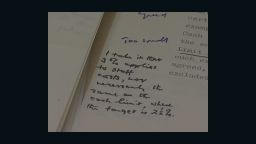

When she entered 10 Downing Street, the prime minister’s official residence, Thatcher headed a Cabinet in which most ministers had voted for her predecessor Edward Heath. Soon, in scribbled comments on the margins of Cabinet papers, the prime minister derided as “wets” those fellow ministers who were aghast at the budgets driven through by herself and Chancellor Geoffrey Howe.

Her colleagues and advisers told her that she could not reform the trades’ unions that had brought the country to its knees during the 1970s through industrial action and seen off the previous Conservative government. Only governments run by Labour - the Conservatives’ main rivals for power – could do that, they said. But Thatcher brought the unions under control and no government since has reversed the measures she took.

READ: Tributes paid to ‘great leader, great Briton’

Diplomats and ambassadors told her she could not get back from the European Union what she liked to refer to as “our money,” the contribution paid by the UK as part of its membership of Europe. But Thatcher “handbagged” her way through European summits till the UK secured a unique budget rebate which no prime minister has dared to negotiate away ever since.

Unafraid to go to war, at home and in the Falklands

Above all, advisers told her there was no prospect of fighting a far-away war and winning back the Falklands Islands after Argentina’s invasion in 1982 – but she did. As the late Washington diplomat Lawrence Eagleburger later confirmed, it was U.S. officials’ fear of her personal wrath which brought crucial intelligence help from Washington.

With her program of selling off homes rented to tenants by regional councils and the privatization of state-controlled industries, Thatcher founded popular capitalism in Britain. Nobody would understand what was meant by “Heathism” or “Wilsonianism” or even “Blairism,” all creeds associated with previous prime ministers. But the British people still have a clear idea of what Thatcherism was all about.

Thatcher took power in a period when most commentators and politicians had accepted that the only role for Britain was the least painful management possible of gentle decline. Instead, she restored a sense of national pride and purpose, enabling Britain to continue punching above its weight in international affairs.

By taking on the power of the trades’ unions, many say she gave managements back the power to manage. But in her revolutionary march through the institutions of British society, she didn’t go as far as many Thatcher zealots would have liked, especially when it came to introducing the open market to health and education services.

WATCH: Falklands War clouds Thatcher’s legacy

Soviets respected her as ‘The Iron Lady’

Overseas, Thatcher became a true power broker on the international scene, seeing Russia’s President Mikhail Gorbachev as a man with whom she could “do business” and re-charging her ideological batteries in exchanges with U.S. President Ronald Reagan.

The “Iron Lady,” as the Moscow media christened her, became a world figure. Her fondness for Ronald Reagan did not stop her bawling him out in 1983 when he allowed American forces to invade Grenada, a member of the Commonwealth, or telling him off for (in her view) conceding too much to Gorbachev in arms negotiations. But she engendered respect rather than love, especially when she fought the rest of the Commonwealth by opposing economic sanctions against the apartheid regime in South Africa.

The authority she gained did not mean there were not mistakes along the way. Some economists blame her governments for wrecking British manufacturing. They say it was under Thatcher’s financial ministers that chronic underspending on Britain’s public services created problems that are still being rectified today. Critics contend that hers was not a tolerant society and she ensured that Britain’s role in Europe become that of permanent irritant rather than profitable partner.

Aided and abetted by sections of the media, it seemed Thatcher came to believe in the myth of her own invincibility. That was what led her into mistakes including the poll tax – a charge that saw dukes and domestic cleaners paying the same local dues – and increasingly shrill anti-Europeanism, which alarmed even her own party and eventually led them to discard a leader who had won them three consecutive elections.

U.S. political figures react to Lady Thatcher’s death

Proud but isolated

Thatcher’s vote-winning drive had forced Britain’s other parties to change their thinking to remain in touch with the electorate. But when the poll tax - a levy on individuals – and her “no, no, no” response to Europe frightened her party into dumping her in 1990, they woke up the next morning and felt guilty about what they had done to their one-time heroine.

Many Tories then adopted Euro-skepticism as a badge of loyalty to the discarded leader and made the party virtually unleadable under Thatcher’s successor John Major. As her friend the novelist Jeffrey Archer put it, this turned the Conservative party into the only known example of a “circular firing squad.” The appealing certainties of a “conviction politician” had turned a party that had been interested previously in the gaining and retention of power into an ideological sect more concerned with winning arguments than elections.

During Thatcher’s party leadership she purged her team of moderates who backed previous leaders like Ted Heath as well as other doubters. She quarreled with other strong figures like Chancellor Nigel Lawson and leadership rival Michael Heseltine, and she sought compliant government officials, inquiring in advance of key Civil Service appointments: “Is he one of us?”

By the time she fell out with Howe, provoking him to deliver a ministerial resignation speech which began her own downfall, he was the only survivor of her first Cabinet.

Thatcher’s strength and drive made her an icon to conservatives in many parts of the world, especially in eastern Europe. She possessed the certainties of a tabloid newspaper editor, and her eagerness to see the power of central government reduced even made her a heroine to some of today’s Tea Party enthusiasts in the United States. Few European politicians since have been so capable of drawing an American audience.

The irony though is that while her election results show the pull she exerted through her strong leadership, her populist streak and her raising of the British profile, many Britons never really identified with the underlying values of the woman who became, both in her time as prime minister and in the years to come, a national icon.

READ: Opinion: Thatcher biopic ‘useful propaganda’ for UK Conservatives