Go to CNNiReport.com to share your memories, tributes and thoughts on Thatcher’s death.

Story highlights

Thatcher, Britain's "Iron Lady," died after suffering a stroke Monday, her spokeswoman said

She retired from public life in 2002 after a stroke

As British PM from 1975 to 1990, she played a key role in ending the Cold War

But Thatcher opposed reunification of Germany

Former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, a towering figure in postwar British and world politics and the only woman to become British prime minister, has died at the age of 87.

She suffered a stroke Monday, her spokeswoman said. A British government source said she died at the Ritz Hotel in London.

Thatcher’s funeral will be at St. Paul’s Cathedral, with full military honors, followed by a private cremation, the British prime minister’s office announced.

Thatcher served from 1975 to 1990 as leader of the Conservative Party. She was called the “Iron Lady” for her personal and political toughness.

She retired from public life after a stroke in 2002 and suffered several strokes after that.

She made few public appearances in her final months, missing a reception marking her 85th birthday hosted by Prime Minister David Cameron in October 2010. She also skipped the July 2011 unveiling of a statue honoring her old friend Ronald Reagan in London.

In December 2012, she was hospitalized after a procedure to remove a growth in her bladder.

WORLD REACTION: Tributes paid to ‘great leader, great Briton’ Thatcher

Thatcher made history

Thatcher won the nation’s top job only six years after declaring in a television interview, “I don’t think there will be a woman prime minister in my lifetime.”

During her time at the helm of the British government, she emphasized moral absolutism, nationalism, and the rights of the individual versus those of the state – famously declaring “There is no such thing as society” in 1987.

Nicknamed the “Iron Lady” by the Soviet press after a 1976 speech declaring that “the Russians are bent on world dominance,” Thatcher later enjoyed a close working relationship with U.S. President Reagan, with whom she shared similar conservative views.

But the British cold warrior played a key role in ending the conflict by giving her stamp of approval to Soviet Communist reformer Mikhail Gorbachev shortly before he came to power.

“I like Mr. Gorbachev. We can do business together,” she declared in December 1984, three months before he became Soviet leader.

Having been right about Gorbachev, Thatcher came down on the wrong side of history after the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, arguing against the reunification of East and West Germany.

Allowing the countries created in the aftermath of World War II to merge would be destabilizing to the European status quo, and East Germany was not ready to become part of Western Europe, she insisted in January 1990.

READ: Why Thatcher was both icon and outcast

“East Germany has been under Nazism or Communism since 1930. You are not going to go overnight to democratic structures and a freer market economy,” Thatcher insisted in a key interview, arguing that peace, security and stability “can only be achieved through our existing alliances negotiating with others internationally.”

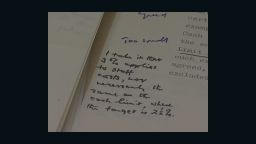

West German leader Helmut Kohl was furious about the interview, seeing Thatcher as a “protector of Gobachev,” according to notes made that day by his close aide Horst Teltschik.

The two Germanies reunited by the end of that year.

A grocer’s daughter

Thatcher – born in October 1925 in the small eastern England market town of Grantham – came from a modest background, taking pride in being known as a grocer’s daughter. She studied chemistry at Oxford, but was involved in politics from a young age, giving her first political speech at 20, according to her official biography.

She was elected leader of the Conservative Party in 1975, when the party was in opposition.

She made history four years later, becoming prime minister when the Conservatives won the elections of 1979, the first of three election victories to which she led her party.

As British leader, Thatcher took a firm stance with the European Community – the forerunner of the European Union – demanding a rebate of money London contributed to Brussels.

Her positions on other issues, both domestic and foreign, were just as firm, and in one of her most famous phrases, she declared at a Conservative Party conference that she had no intention of changing her mind.

“To those waiting with bated breath for that favorite media catchphrase, the U-turn, I have only one thing to say: ‘You turn if you want to. The lady’s not for turning,’” she declared, to cheers from party members.

The United Kingdom fought a short, sharp war against Argentina over the Falklands Islands under Thatcher in 1982, responding with force when Buenos Aires laid claim to the islands.

WATCH: Remembering Margaret Thatcher

Announcing that Britain had recaptured South Georgia Island from Argentina, Thatcher appealed to nationalist sentiments, advising the press: “Just rejoice at the news and congratulate our forces.”

A journalist shouted a question at her as she turned to go back into 10 Downing Street: “Are we going to war with Argentina, Mrs. Thatcher?”

She paused for an instant, then offered a single word: “Rejoice.”

Controversy over Falklands war

The conflict was not without controversy, even in Britain.

A British submarine sank Argentina’s only cruiser, the General Belgrano, in an encounter that left 358 Argentines dead. The sinking took place outside of Britain’s declared exclusion zone.

In her first term, Thatcher reduced or eliminated many government subsidies to business, a move that led to a sharp rise in unemployment. By 1986, unemployment had reached 3 million.

But Thatcher won landslide re-election in 1983 on the heels of the Falklands victory, her Conservative Party taking a majority of seats in parliament with 42% of the vote. Second-place Labour took nearly 28%, while the alliance that became the Liberal Democrats took just over 25%.

A year later, she escaped an IRA terrorist bombing at her hotel at the Conservative Party conference in Brighton.

She was re-elected in 1987 with a slightly reduced majority.

She was ultimately brought down, not by British voters, but by her own Conservative party.

READ: Artistic opposition to the “Iron Lady”

Brought down by the poll tax

She was forced to resign in 1990 during an internal leadership struggle after she introduced a poll tax levied on community residents rather than property.

The unpopular tax led to rioting in the streets.

She married her husband, Denis Thatcher, a local businessman who ran his family’s firm before becoming an executive in the oil industry, in 1951 – a year after an unsuccessful run for Parliament. The couple had twins, Mark and Carol, in 1953.

She was elected to Parliament in 1959 and served in various positions, including education secretary, until her terms as prime minister.

Thatcher was awarded the U.S. Medal of Freedom by President George H. W. Bush in 1991, a year after she stepped down as prime minister. She was named Baroness Thatcher of Kesteven after leaving office.

She retired from public life after a stroke in 2002 and suffered several smaller strokes after that. Her husband died in June 2003.

Though her doctors advised against public speaking, a frail Thatcher attended Reagan’s 2004 funeral, saying in a prerecorded video that Reagan was “a great president, a great American, and a great man.”

“And I have lost a dear friend,” she said.

In the years that followed she encountered additional turmoil. In 2004, her son Mark was arrested in an investigation of an alleged plot by mercenaries to overthrow the president of Equatorial Guinea in west Africa. He pleaded guilty in a South African court in 2005 to unwittingly bankrolling the plot.

WATCH: Kissinger: Thatcher’s strong convictions

U.S. political figures react to Lady Thatcher’s death

CNN’s Laura Perez Maestro, Vicky Bennett and Nick Hunt contributed to this report.