Explore the Rijksmuseum’s most treasured possession, Rembrandt’s “Night Watch” in our interactive.

Story highlights

New setup is radically different

10-year refurbishment cost €375 million ($489 million)

There are 80 rooms and 8,000 artworks

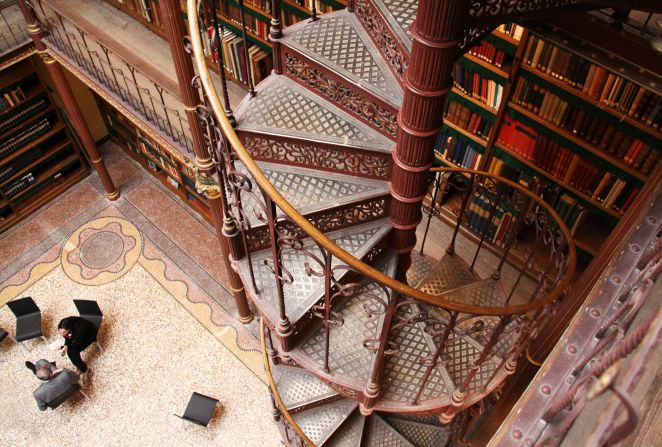

Closed for 10 years for an all-encompassing, €375 million ($489 million) refurbishment, Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum – the national museum of arts and history founded in 1800 – has emerged transformed and resplendent.

Gone is the labyrinth-like gloomy edifice that, for all its artistic treasures, felt rooted in the past and imbued with melancholy.

The lead architects of the redesign, Spanish practice Cruz y Ortiz, have harkened back to the original design of architect Pierre Cuypers, who completed the project in 1885.

The airy atrium is back, where visitors can plan their route around eight centuries, 80 rooms and 8,000 artworks.

Cuypers’ original plan for accessing the museum also made a return.

Visitors ascend an ecclesiastically inspired hallway, entering the 17th century gallery under the gaze of the greats of philosophy, art and literature.

Main draws

Dedicated to the art of Holland’s Golden Age and adorned with restored frescoes, the museum’s 17th century gallery is home to an impressive selection of masterpieces.

Of them, two are likely to be the Rijksmuseum’s biggest crowd-pullers.

One is “The Milkmaid” by Johannes Vermeer. Depicting a humble domestic servant at work in a kitchen, the painting is known to possess a veiled sexuality. (Does the small Delft tile depicting Cupid in the background imply that the heroine is day-dreaming about her lover?)

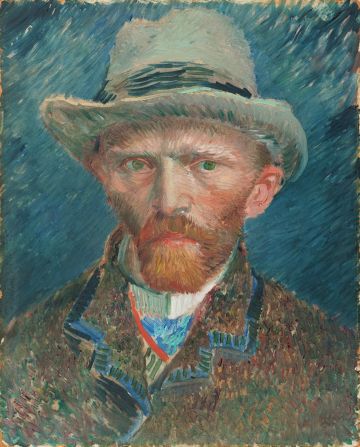

The second is Rembrandt van Rijn’s “The Night Watch,” dubbed the museum’s “altarpiece” by its director Wim Pijbes.

Measuring 11 feet by 14 feet, this dramatic rendition of a unit of 17th century troops, complete with feather plumes, lace collars and gleaming weapons, is the only item that has not changed location as part of the refurbishment.

Interactive: Rembrandt’s ‘Night Watch’ explained

“When you enter the Rijksmuseum you’re transported to another world – the world of Rembrandt, Vermeer and Mondrian,” says Taco Dibbits, director of collections.

“I think it’s the only national museum in the world that is not only a museum of painting, not only a museum of the decorative arts, but also a museum of history.”

Collections

The new galleries bring together paintings with a range of objects from the same era.

“We were interested in giving the public a sense of beauty in context,” says Dibbits.

Items are arranged chronologically.

Rembrandt’s works, for example, are displayed alongside silverware and furniture made by craftsmen whom the great master would have known.

New approach

The new setup is a radically different approach to how the museum used to be.

Before the renovation, galleries were arranged thematically: paintings with paintings, ceramics with ceramics and sculpture with sculpture.

The chronological approach posed challenges for the man charged with making the displays clear and concise: Jean-Michel Wilmotte, architect of museum scenography.

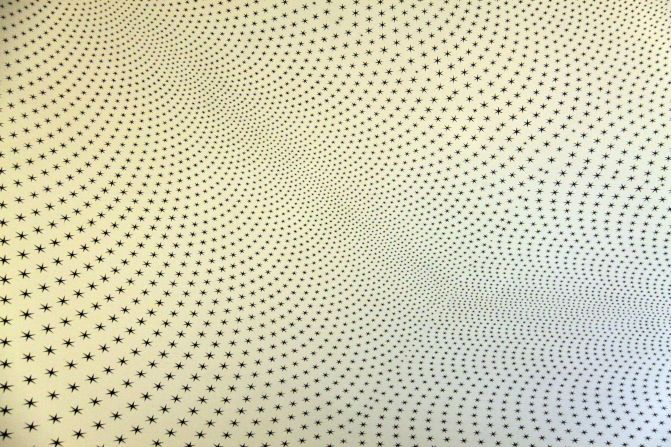

“We needed to find a color that provided a kind of guideline to create unity around the museum,” says Wilmotte.

His answer was to have the walls in the galleries painted in shades of gray, ranging from very pale in the 20th century displays to echo the hues of steel and aluminum associated with that era’s technological advances – to deep and dark hues in the medieval galleries.

This way, the walls not only provide a dramatic backdrop for the gold and silver items on show but also evoke the shadows of a crypt or the inner sanctum of some great cathedral.

Thoughtful arrangements

Wilmotte has also worked wonders with the displays themselves.

In the Special Collections gallery on the ground floor, ivory-handled flintlock pistols seem to float in the air. In another cabinet a large number of magic lantern slides depict animals, battles and 18th century raunchiness.

Further on, a hammock of 17th century admiral Cornelius de Witt hangs above the simple campaign bed of William of Orange, the Dutch prince wounded at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815.

There’s a lot of depth and drama in the new displays and, whereas the paintings of the Dutch masters may have had the power to stand alone, in other areas it is often the associated objects that are the most intriguing and emotive.

“You can see paintings, china and woodwork together – you are not just visiting a museum, you are deep in a different century,” says Wilmotte. “This is unique.”

Sinister gift

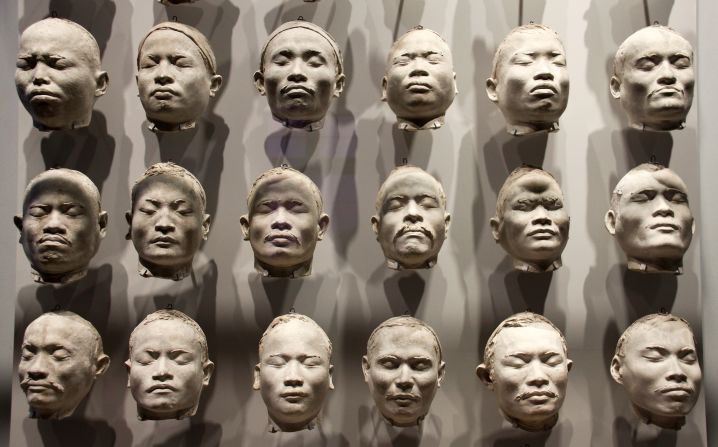

The 20th century gallery on the top floor is home to perhaps the most sinister item in the museum.

It looks like a large, ugly, ostentatious chess set at first sight, but look closer and the pawns are helmeted soldiers, the rooks howitzers and the bishops fighter aircraft.

The set was a gift from leading Nazi Heinrich Himmler to Anton Mussert, a senior figure in the Dutch National Socialist party, as a reward for his loyalty.

Juxtaposed with the uniform of a concentration camp survivor, it speaks volumes about a deeply disturbed period of history and comes as something of a shock after the measured pomp and tranquil domesticity of the 17th century galleries for which the museum has so long been famous.

The museum reopens April 13, 2013.

Museumstraat 1, Amsterdam, Netherlands; +31 20 662 1440; open daily 9 a.m.-6 p.m.; €15 ($20) for adults, free for 18 and under; www.rijksmuseum.nl

More on CNN: Insider Guide - Best of Amsterdam

More on CNN: Rembrandt’s ‘Night Watch’ explained