Story highlights

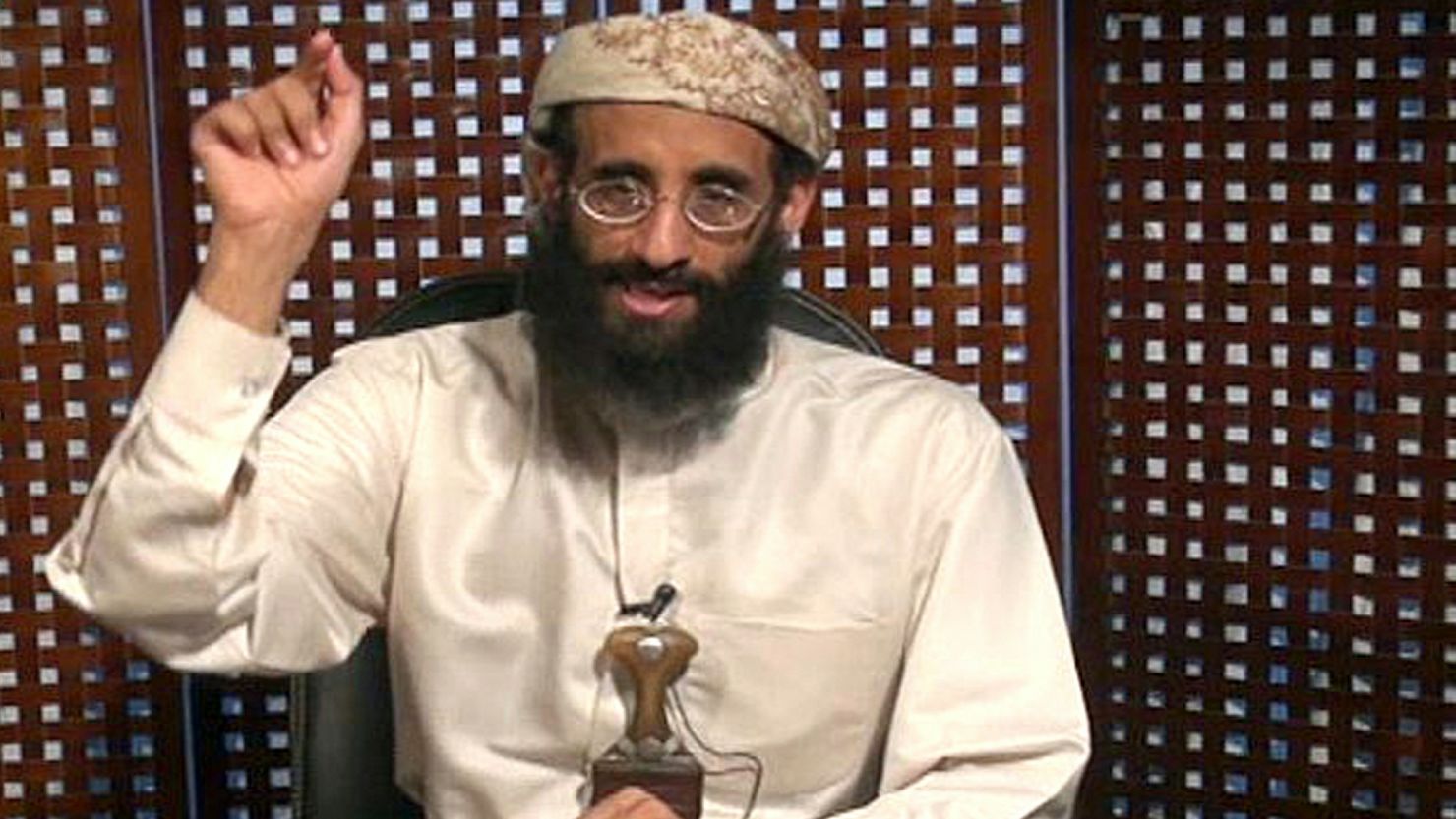

Though he's dead, militant cleric Anwar al-Awlaki remains influential

Investigators suspect the Tsarnaev brothers listened to his sermons online

The brothers might have downloaded bomb-making instructions, officials say

He was born and raised in the United States, and killed by the United States. And now from beyond the grave he inspires a new generation of would-be terrorists to attack the United States.

Militant cleric Anwar al-Awlaki continues to speak through sermons posted online, and U.S. officials are investigating whether his words may have influenced Boston bombers Tamerlan and Dzhokhar Tsarnaev.

A U.S. government official told CNN’s Jake Tapper on Tuesday that “the preachings of Anwar al-Awlaki were likely to have been among the videos they watched.” A U.S. government source had previously told CNN that Dzhokhar Tsarnaev had claimed the brothers had no connection to overseas Islamist terrorist groups and were radicalized through the Internet.

Al-Awlaki lived in Colorado, California and Virginia before leaving the United States in 2002. At one point he met two of the men who would be among the 9/11 hijackers, an encounter later investigated by the FBI. There is no evidence that al-Awlaki knew of their plans.

From about 2006 onward he became increasingly influential among would-be jihadists around the world with his eloquent online sermons delivered in fluent and colloquial English. Al-Awlaki was killed in a U.S. drone strike in a remote part of Yemen in September 2011, along with another American, Samir Khan.

U.S investigators are examining whether the Tsarnaev brothers downloaded or viewed a bomb formula that appeared in Inspire, the online English-language magazine published by al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula. Al-Awlaki is believed to have been the driving force behind that magazine and Samir Khan was its editor.

The pressure cooker devices exploded in Boston had several striking similarities to a design in the first issue of the magazine in the summer of 2010 “How to build a bomb in Your Mom’s Kitchen.”

The magazine instructed would-be jihadists in the West to deploy multiple devices and set them off simultaneously in a crowded space. Another issue of the magazine published a year ago called for attacks at crowded sports venues.

The Inspire recipe “How to Build a Bomb in your Mom’s Kitchen” has been linked to multiple Islamist terrorist plots on both sides of the Atlantic. It was downloaded by a group of Islamist extremists plotting to bomb London in late 2010.

In July 2011, an American Muslim soldier from Fort Hood, Texas – Naser Jason Abdo – downloaded the recipe and bought pressure cookers and shotgun shells from which he could extract explosive powder. Abdo was arrested before he had assembled a bomb and was sentenced last year to two consecutive life prison sentences for attempted use of a weapon of mass destruction.

New York resident Jose Pimentel allegedly began building a pipe bomb using the recipe before being arrested by New York police in November 2011. Pimentel was charged with plotting to bomb targets in the United States; he has pleaded not guilty.

The Emergence of a “jihadist rockstar”

Awlaki was born in New Mexico. He spent some time in Yemen as a teenager before coming back to the United States. His time in America helped him speak to radicals in a language they could understand and grasp the vulnerabilities of open societies in the West.

His sermons were sometimes impassioned and dwelt on the topic of jihad, but many mainstream Muslims did not then regard him as an extremist.

After leaving the United States, al-Awlaki intensified his preaching – recording DVD sermons that became extremely popular among Islamists across the Western world. He spent time in London and was very popular among congregations in more radical mosques with his sermons on the injustices he alleged were being perpetrated by the West against Islam.

As one East London imam later put it, “He left the congregations all revved up with nowhere to go.”

Behind closed doors, it was a different story. In small study circles al-Awlaki spoke out in favor of suicide bombings in the West, according to one British imam. One such meeting was attended by undercover MI5 agents, prompting British authorities to ban him from traveling to the United Kingdom, the imam told CNN.

Avid consumers of al-Awlaki’s videos included the so-called Toronto 18, who plotted to launch attacks across Canada in 2006, and the British al Qaeda cell that plotted to bomb trans-Atlantic airliners the same year.

Several of those who plotted to attack the Fort Dix military base in New Jersey in 2007 were also big fans of the cleric’s sermons. And two of the al Qaeda terrorist cell that plotted to bomb New York subways in 2009 later admitted they were radicalized by al-Awlaki’s sermons.

Al-Awlaki eventually resettled in Yemen, where he made clear to followers that he supported al Qaeda’s campaign of violence against the United States.

In 2006, al-Awlaki was imprisoned by Yemeni authorities and was interviewed by FBI officials. His former friends have told CNN that when al-Awlaki was released 18 months later he was a changed man, hardened by the experience. And he began communicating with admirers around the world.

One of them was Maj. Nidal Hasan of the U.S. Army, who had once attended al-Awlaki’s sermons at a mosque in Falls Church, Virginia. On December 17, 2008, Hasan sent the cleric the first of what would become a stream of e-mails. He wanted to know if Awlaki considered American Muslim soldiers who turned their guns on their fellow soldiers martyrs. Not long afterward the cleric replied.

In one e-mail, Hasan said he could not wait to join al-Awlaki in the afterlife, where they could have discussions over non-alcoholic wine. Two FBI task forces had reviewed the intercepted e-mails and concluded there were no grounds for action against Hasan, that the messages could be construed as a legitimate part of his work as an army psychologist.

But on the morning of November 6, 2009, Hasan gunned down 13 U.S soldiers at the Fort Hood military base in Texas, and those communications were seen in a very different light.

Al-Awlaki did nothing to distance himself from Hasan’s attack. Within two days of Fort Hood, the cleric wrote on his website: “Nidal Hasan is a hero. … The US is leading the war against terrorism, which in reality is a war against Islam.”

By then al-Awlaki had begun orchestrating a potentially much more deadly plot against the United States. In the late summer and fall of 2009 he recruited a young Nigerian for the mission, according to sources who were close to al-Awlaki at the time. Umar Farouk AbdulMutallab had come to Yemen in the hope of meeting the cleric.

According to U.S. court documents, when the two met they discussed martyrdom and jihad for three days. By the end of that time, the young Nigerian told the cleric he was ready for any mission, martyrdom included.

Weeks later, on Christmas Day 2009, AbdulMutallab came close to destroying Northwest Airlines Flight 253 on its final descent into Detroit with an explosive device hidden in his underwear. According to the U.S. government, al-Awlaki was intimately involved in planning the operation.

In the following months a new wave of plots emerged linked to the preaching of al-Awlaki. On May 1, 2010, Faisal Shahzad, an American-Pakistani recruited by the Pakistani Taliban, attempted to blow up a car bomb in New York’s Times Square. Investigators later discovered that he had been inspired by al-Awlaki’s preaching about violent jihad.

In October 2010, al-Awlaki was involved with a new attempt by al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula to blow up U.S.-bound aircraft by inserting explosive devices in printer cartridges destined for the United States. Investigators later described the hidden devices as very sophisticated and well camouflaged, and the plot was thwarted only thanks to a tip-off from Saudi intelligence. The bombs were intercepted while en route.

By 2011, Inspire magazine had a simple message for followers in the United States: Stay where you are and launch attacks at home. Its reach continued to grow around the world. CNN has established that the Dagestan wing of the Caucasus Emirate, a jihadist group fighting to create an Islamic state in the region, posted a Russian language translation of a 2012 issue on their website, along with videos of al-Awlaki.

Tamerlan Tsarnaev posted a link to a video by a local commander of the group – Abu Dujana – on his YouTube site after traveling to Dagestan in 2012.

Even in death al-Awlaki’s influence has persisted. In May 2012 a posthumous article in his name was published in which he sought to justify biological and chemical attacks against the United States.

The magazine proclaimed: “We are still publishing America’s worst nightmare. … All of his students will follow his steps and this is how we win.”