Story highlights

Marcus Urban was an East German footballer who retired to live as openly gay

A talented midfielder Urban represented East Germany as a youth international

NBA player Jason Collins "came out" in an interview with Sports Illustrated last month

Former United States midfielder recently announced he was after retiring from soccer

Four walls, a bed and a slop bowl. If prison represents physical confinement and a loss of every personal freedom, what does imprisonment of the mind feel like?

“Unbearable” according to Marcus Urban, a German footballer who gave up his chosen profession – his “first love” – because of homophobia in the game.

In a sport infamous for macho bravado on the pitch and anti-gay chants in the terraces, Urban was battling an unspeakable shame.

A promising talent, Urban in his youth played alongside and against future German national team stars Robert Enke, Bernd Schneider and Thomas Linke.

Read: Nothing black and white for Italy’s football “ultras”

“To play soccer basically means to rejoice in life,” Urban told CNN. “I never stopped playing football. It has always been my first love and it will remain forever.”

But, as is the case with so many first loves, Urban’s left him with a heartbreak which was almost too much to bear.

Read: In search of a gay football hero

The young midfielder, born and raised in East Germany in the 1970s and 80s in the days before reunification with West Germany in 1990, dreamed of representing his country – but he was living an exhausting double life.

On the surface he was a rising football star, but beneath he was a man coming to terms with his homosexuality.

Read: Thiago Silva’s World Cup ambition

“I hid 24 hours a day, I adjusted,” explained Urban, who was terrified of being “outed” in a sport which today has just one openly gay professional player in Europe.

“It was an almost unbearable pain, a great sacrifice, a painful price to pay to achieve my goal of becoming a professional footballer.

“Constantly hearing gay used as a curse word like s**t, made me think, ‘Of course, I’m s**t.’ I spent 50% of my energy trying to hide, so a maximum of 50% of my energy was available for football. It wasn’t fair.

“I kept thinking, ‘I cannot do this anymore, I don’t want to. What is going on?’ Nobody was there to help me.”

Read: Seven moments which defined Alex Ferguson

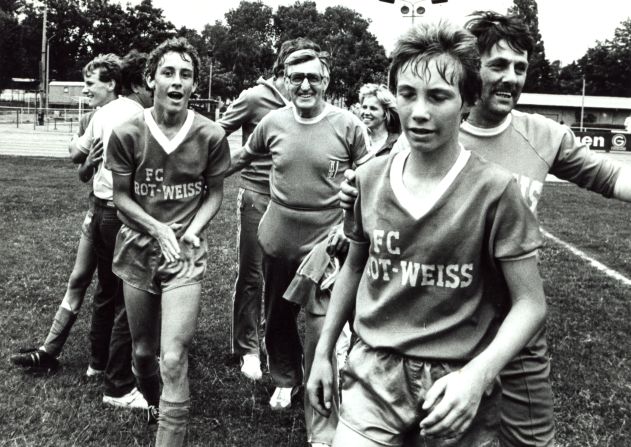

Urban’s love affair with football began in 1978, when he joined East German club Motor Weimar at the age of seven before moving to Rot-Weiss Erfurt in 1984.

He trained twice a day with his new team and looked capable of achieving his ambition of playing for the German national team, winning a youth championship with Rot-Weiss in 1985.

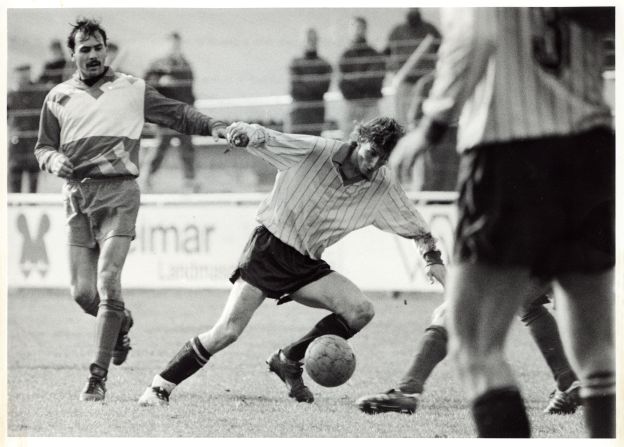

His reputation was growing and he was called up to East Germany’s youth team in 1986. Urban went on to make over 100 appearances for Rot-Weiss’ senior team in the German second division.

But rather than marking the start of his rise to the top of German football, Urban’s spell in Erfurt proved to be the peak of a career cut short by fear, insecurity and self-loathing.

“By my early 20s I was burned out,” he said.

“I realized that if I became a professional footballer, I would suffer as a man. I chose freedom over a constructed prison.

“Talent is not enough. You need the will, physical fitness, good luck and a tough mentality. But what if you hide 24 hours a day because you are gay?

“The fear and pain robbed me of my energy because I was constantly thinking of what to say, how to act so people might think I was heterosexual.”

When it became clear he was in the twilight of his playing career, Urban finally summoned the courage to open up to one of his teammates following a switch to provincial club SC 1903 Weimar in 1991.

“I told only one player, in Weimar at the end of my career – and precisely for this reason,” said Urban. “He found it interesting that I was gay, I was one of his best friends on the team.”

Compared to other areas of society, the football profession is statistically lacking in openly gay players.

Former United States national team player Robbie Rogers recently announced he was gay on the same day he retired from the sport, while Sweden-based Anton Hysen is currently the only openly “out” player in Europe.

Justin Fashanu’s tragic story is the last time a top-flight player has been so open.

The Englishman committed suicide in 1998, aged 37 – just eight years after announcing that he was gay. He had become the first £1 million black player when he joined Nottingham Forest in 1981.

Speaking at a sports forum in Berlin last September, German chancellor Angela Merkel urged gay players to feel confident enough to “come out.”

Her comments came following an article in a German magazine in which an anonymous gay Bundesliga player said the fear of added media attention was the reason why he hadn’t announced his sexuality.

German second division team FC St. Pauli placed itself on the front line of football’s battle with homophobia during a match with Paderborn.

Fans of the club, formerly run by openly gay president Corny Littmann, staged a demonstration against discrimination which included brightly-colored posters and a banner reading, “Football is everything – even gay.”

Basketballer Jason Collins recently made history by becoming the first openly gay NBA player, while the NHL has drawn plaudits for its anti-homophobia work.

Fifteen years on from Fashanu’s suicide, with other sports such as rugby and basketball setting a precedent and with the NFL reportedly closer than ever to having a homosexual player, is the beautiful game ready for a high-profile gay star?

“Why not?” replied Urban. “It is a great opportunity for the football world to show now that it is ready. Associations and clubs can come out as ‘gay-friendly’. Then players, officials, coaches, referees and so many others will follow.

“The effects of outings gay footballers will go far beyond football.”

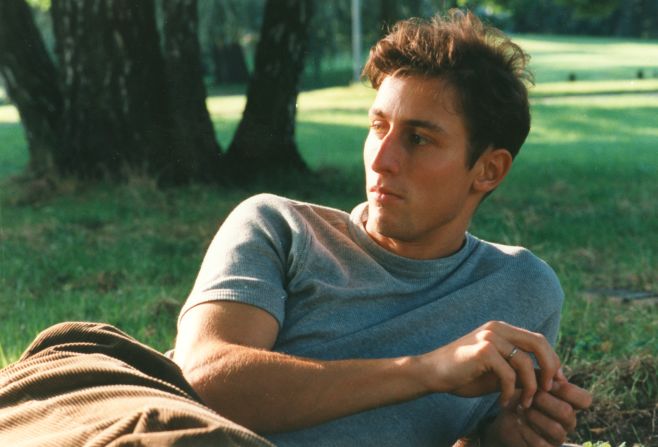

After years of torment and secrecy, Urban’s coming out proved to be a turning point. With new-found confidence, he was able to pursue a life away from the football pitch.

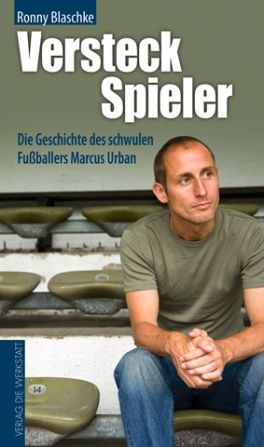

Urban has told his story in the book “Hidden Player: The story of a gay footballer,” while he is also something of a life coach, consulting with organizations – including football associations – on issues of diversity and integration.

“I was so glad to finally be myself and I finally knew what the years of torment had been about,” he explained. “With the energy and force of liberation I went on the front foot, on the offensive.

“I work as a personal coach and diversity consultant. I work for organizations and I help them to appreciate the dimensions of age, ethnicity, gender, religion and even sexual orientations.”

With a wealth of personal and professional expertise on the subject of “coming out,” Urban is in a unique position to offer advice to any player in a similar situation to the one he found himself in two decades ago.

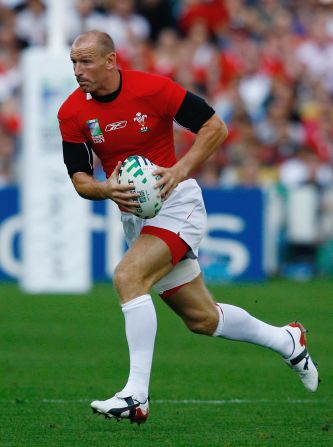

According to Urban, former Wales international rugby player Gareth Thomas – who told the world he was gay in 2009 – has set out the perfect blueprint for others to follow.

“He proceeded in stages,” Urban said of Thomas. “First he outed himself to his wife. Then he told his coach and then two players. After each step he received positive feedback.

“He was told by everyone that he was still the same person. This enabled him to increase his self-esteem until it was big enough to go public. He then got exceptionally positive feedback.”

An openly gay football star would be a turning point not just for the sport, declares Urban, but also for society as a whole.

Football, he suggests, stretches into areas where attitudes towards homosexuality have so far proved difficult to change.

“Football is the only way to tackle this topic comprehensively,” he said. “Very many people are geared towards football role models on television.

“If world soccer stars accepted their homosexuality, young people would question having to be so rough and macho.

“The result would be a social change that goes far beyond football.”

Urban is now comfortable with his sexuality, but he is not impervious to the homophobic barbs he often overhears in general conversation.

“‘F****, f****t’, any negative way of calling someone gay,” replies Urban when asked which insults he hears. “I was constantly affected by insults. Although it is not said to me directly it concerns me, even today.”

“But today, with more self-esteem and confidence, I look at homophobia from the perspective of a personal coaches and diversity consultant. Sometimes I have to laugh about it too, because it’s stupid and ridiculous.”

Self-esteem and confidence have helped Urban to heal the wounds inflicted by his first love, football.

He is once more besotted with the sport, playing with and against gay-friendly teams from across the globe.

It might not be playing at a World Cup with the German national team, but Urban is now back on the pitch, this time with his head held high.

“I really wanted to play for the men’s national team,” reflected Urban. “It makes me happy to have made something out of my experiences.

“For years I could never play football in the stadium. I saw the grass and could not stand being a spectator rather than being down playing on the pitch. I had regrets, I was sad and angry.

“After I came out I was so much more confident. I played football at university, in a team consisting predominantly of gay footballers against other gay teams from Paris, London or New York and Washington.

“Today, I play at a club in Hamburg, accepted by everyone and my teammates are proud of me, I think. It is a great experience to play football and to feel free, pure happiness.

“There are certainly more boring lives than mine.”