Story highlights

Champions League final provides a "brilliant showcase" for "Brand Germany"

Bundesliga clubs have strong "indigenous corporate engagement"

Expert: Sponsor and fan cooperation is for the clubs' greater good

Like German businesses, Bundesliga clubs pursue long-term planning

When Germany’s two biggest soccer clubs go head-to-head in Saturday’s Champions League final, there can only be one winner: German industry.

The Bavarians of Bayern Munich will look to rectify last year’s heartbreak on home soil against Chelsea when they take on a formidable Borussia Dortmund side that is seeking to emulate the club’s only success in Europe’s top competition, back in 1997.

Some of the biggest talents in world football will be on show at Wembley come kickoff at 1845 GMT in London, with the likes of Arjen Robben, Franck Ribery and Robert Lewandowski set to dazzle the crowd.

But the all-Bundesliga final could just be the sideshow to a bigger German act, as billion-dollar corporates gear up for one of the major advertising opportunities in world sport.

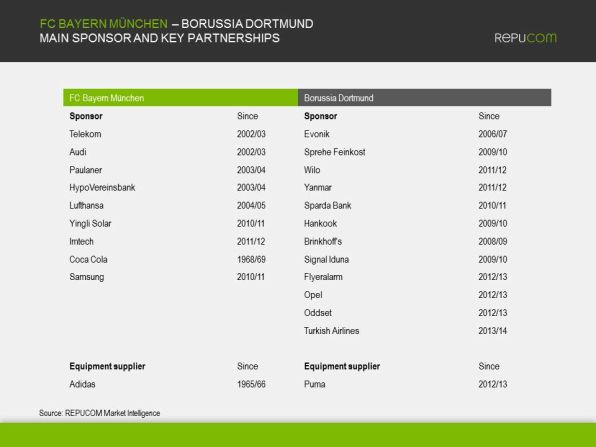

From sportswear multinationals such as Adidas and Puma to insurance giants Allianz and Signal Iduna, Wembley stadium will be awash with the household names of German commerce – all helpfully beamed to a global television audience of potentially 150 million.

Thousands of toxic yellow and crimson red jerseys will sport the names of Dortmund’s sponsor – chemical manufacturer Evonik – and that of Bayern – Deutsche Telekom – as Europe’s largest economy struts its industrial might on club football’s most prestigious stage.

Read: Double trouble for Bundesliga?

Germany, Europe’s manufacturing powerhouse, is considered one of the economic bright spots of a continent dogged by recession despite the country posting growth of only 0.1% in the first quarter of this year, driven mostly by consumer spending.

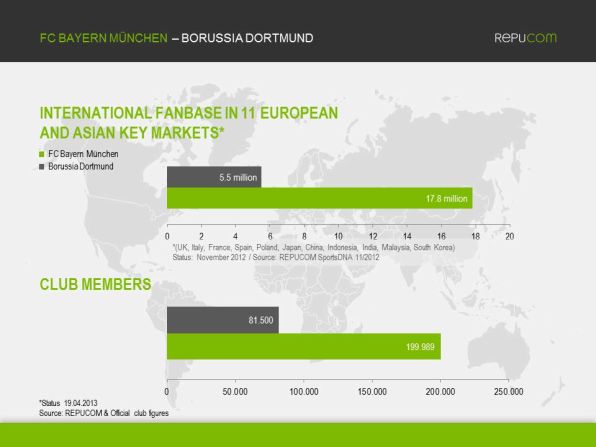

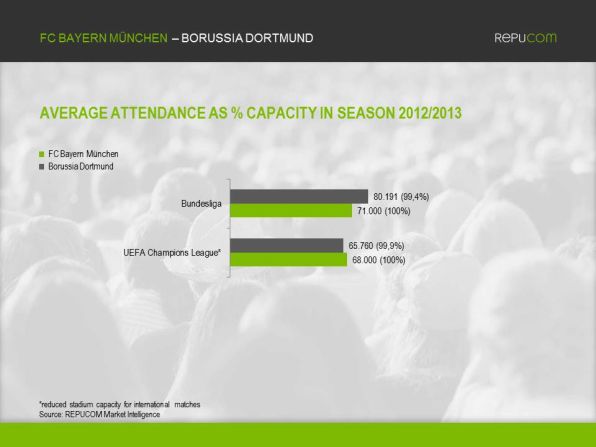

Despite low growth, Germans – recognized as the best savers in Europe – proved they were ready to flaunt their cash as Dortmund received a staggering half a million ticket requests for the final while Bayern received 250,000. Wembley can hold just 90,000 fans.

Football finance expert Simon Chadwick said the final will provide a “brilliant showcase” for “Brand Germany,” adding that the flair and style of the Bundesliga as well as the wide array of homegrown talent on display will enhance the brands connected with the teams.

“Existing brand associations that many people around the world have with German products – notably efficiency and quality – will no doubt be reinforced,” Chadwick told CNN.

Financial model of sustainability

The ties between German industry and football run deep.

Unlike in England, France and Spain, where clubs are backed by Arab sheikhs, Russian oligarchs and American tycoons, the German league prefers a more homely approach to club financing.

Christian Seifert, chief executive officer of the Bundesliga and a self-proclaimed Borussia Monchengladbach fan, is skeptical as to whether the final will boost the national economy, but he does believe the game will be a good advert for German football.

“Bayern and Dortmund are proof that it is possible to have good sporting performance and to have solid financial behavior,” Seifert told CNN.

Unlike other top leagues which attract more global endorsers, the Bundesliga clubs are largely sponsored by domestic brands – 15 of the 18 clubs in Gemany’s top tier for the 2012-13 season were backed by local companies ranging from multi-billion-dollar insurance firms to family chicken and dairy farmers.

“The big difference that you notice between other clubs in Europe is the degree of indigenous corporate engagement,” sports finance expert Tom Cannon told CNN.

Even the stadia are part of the Bundesliga’s “Brand Germany” philosophy.

While fans of Manchester United or Liverpool would scorn at the renaming of Old Trafford as the Aon Arena or Anfield as the Standard Chartered Stadium, regular rechristening is the norm for the 18 Bundesliga teams.

So the Commerzbank Arena – home to Eintracht Frankfurt and located in the country’s financial heartland – is named after one of Germany’s biggest banks. Dortmund’s Signal Iduna Park, once the Westfalenstadion, and Bayern Munich’s Allianz Arena – both tagged by insurers – serve as further examples of the close links with big business in Germany.

Chadwick believes branding stadiums reveals a consensus in football that is characteristic of German society and culture, where sponsor and fan cooperation is seen as for the club’s greater good.

“This shows both a level of commercialism and a certain betrayal of history and heritage that some fans both in Germany and in other countries find unacceptable,” said Chadwick.

Read: All-German final down to youth policy

However, there is one fundamental rule for all Bundesliga teams that ensures fans are not kept in the dark when it comes to the control of their club.

The “50 plus one” rule – a revered model of football governance whereby fans are the majority stakeholder – applies to all clubs participating in the Bundesliga, with the exception of Bayer Leverkusen and Wolfsburg.

Those teams were founded by pharmaceutical company Bayer and car manufacturer Volkswagen respectively and are 100% owned by these companies, with the stadiums – BayArena and Volkswagen Arena – named in their honor.

This is due to a rule that states if a club in Germany receives major financial backing from one party for over 20 years, that party can then take a controlling stake in the club.

The boardroom structure in the Bundesliga is unique and completely different to the big clubs in England, where a relatively small ownership group dominates the board.

“The boards of these (German) clubs are packed with corporate heavyweights,” said Cannon. “It’s a confident assertion of German industry.”

Although Bayern is owned by the fans, both Adidas and carmaker Audi have 9% stakes in the club, with the chairmen of both companies sitting on its supervisory board.

In the case of Dortmund, 82% of the club is free-float stock and owned by the fans but the corporate board is dominated by businessmen with backgrounds in banking and shipping.

Read: Football enters space age with ‘Footbonaut’

Bundesliga boss Seifert insists he is not concerned by the intimacy between big business and football clubs in Germany because the revenue generated by the teams pales in comparison to big multinational brands’ profits.

“I don’t think they’re too close,” said Seifert. “The good thing is that the 100,000 jobs are created through the Bundesliga in Germany.

“We’re talking about global brands and they’re using football as a marketing instrument all over the globe.”

Read: Time for Premier League to give youth a chance, says Hargreaves

The strategy pursued by the German Football Federation and the Bundesliga after a poor showing at the European Championships in 2000 has paved the way for the nation’s current success at both club and international level.

“Each club that wanted to play in the top two tiers of the Bundesliga – 36 clubs – had to have a youth academy,” Seifert said.

“Today more than €100 million ($128 million) per year is invested and 5,000 players are educated in the program.”

Dave Webb, a scout for English Premier League club Southampton who spent time observing the Bayer Leverkusen setup, explained that there has been major investment by Bundesliga clubs at grassroots level – and players coming up from youth level are given more time to flourish than players in the English system.

“Bayern and Dortmund are very strong at youth level and that is behind their success,” said Webb. “Players are judged a bit later in the Bundesliga – instead of 17 or 18, players can go right through to under-21 level before they reach the first team.”

Given that co-ordinated strategy allied to long-term planning, no wonder “Fussball” is coming home – to Germany.