Story highlights

Researchers update their research on Richard III

They say gravediggers appeared to be in a hurry, may have shown disrespect

Archaeologists found the body of a man buried beneath a parking lot in Leicester

DNA tests confirm "beyond reasonable doubt" the identity of the bones

Richard III’s burial was hardly fit for a king.

The awkward position of the English monarch’s body, and the inferior quality of his grave, suggests medieval gravediggers placed him there in a hurry or didn’t care much for him, according to researchers.

Or perhaps both.

British archaeologists, in the first academic paper since the discovery of his skeleton under a parking lot, said Richard’s body was buried in Leicester, central England, “with minimal reverence.”

The king, 32, was killed at the Battle of Bosworth Field in 1485. It was the last fight in the War of the Roses, which ended with the ascension of Henry VII and the Tudors.

Richard’s naked body was returned to Leicester for public display before he was interred three days after death.

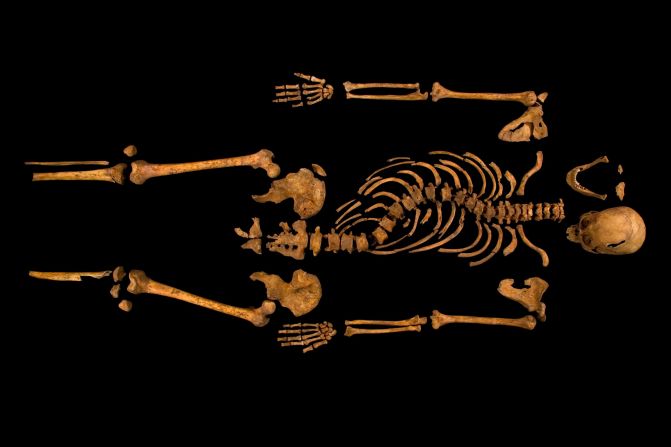

His torso was lowered into a too-short grave, leaving it in an “odd position” that left the head partially propped up against the grave side.

“Only a little extra effort by the gravediggers to tidy the grave ends would have made this grave long enough to receive the body conventionally,” the University of Leicester researchers wrote in an article published Friday in the journal Antiquity. “That they did not, instead placing the body on one side of the grave, its torso crammed against the northern side, may suggest haste or little respect for the deceased.”

They suggested one possible factor.

“The haste may partially be explained by the fact that Richard’s damaged body had already been on public display for several days in the height of summer, and was thus in poor condition.”

Richard was discovered buried among the remains of what was once the city’s Grey Friars friary. Other graves were of correct length and neat rectangular with vertical sides, according to researchers.

“This grave was an untidy lozenge shape with a concave base and sloping sides, leaving the bottom of the grave much smaller than its extent at ground level,” researchers wrote.

There was no evidence of a shroud or coffin.

In February, scientists announced that they were convinced “beyond reasonable doubt” that the skeleton belonged to Richard.

Mitochondrial DNA extracted from the bones was matched to Michael Ibsen, a Canadian cabinetmaker and direct descendant of Richard III’s sister, Anne of York, and a second distant relative, who wished to remain anonymous.

Experts say other evidence – including battle wounds and signs of scoliosis, or curvature of the spine – found during the search and the more than four months of tests since strongly supported the DNA findings.

Richard III met a very violent death

Some of findings have been publicized before.

The king’s feet had been lost at some point in the intervening five centuries, but the rest of the bones were in good condition, which archaeologists and historians say was incredibly lucky, given how close later building work came to them – brick foundations ran alongside part of the trench, within inches of the body.

Archaeologists said their examination of the skeleton shows Richard met a violent death: They found evidence of 10 wounds – eight to the head and two to the body – which they believe were inflicted at or around the time of death.

Wounds to the face and two other cuts to the body may be “humiliation injuries” delivered after death, scientists said.

The skeleton also showed marks that could have come from period-appropriate weapons. In particular, a large wound at the base of his skull seemed likely to have been made by a blade like a halberd. Other wounds seemed similar to those inflicted by daggers and knives of the time.

Richard’s hands also may have been bound.

More recent analysis of the remains, using radiocarbon dating, indicates a high-protein diet, heavy on seafood, indicating a high status in society.

After centuries of demolition and rebuilding work, the exact location of Richard’s grave had been lost to history, and there were even reports that the defeated monarch’s body had been dug up and thrown into a nearby river.

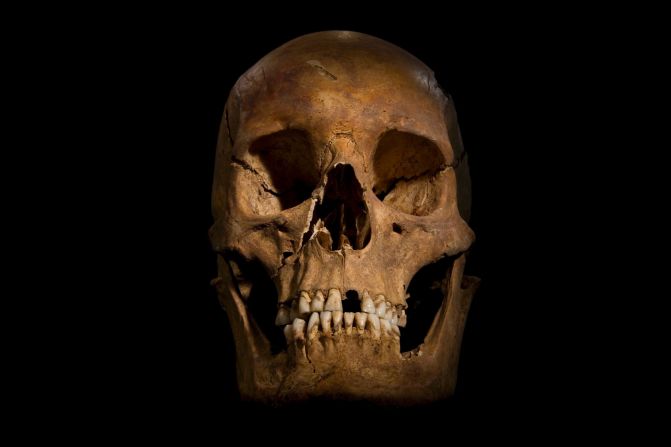

“The skull was in good condition, although fragile, and was able to give us detailed information,” bioarchaeologist Jo Appleby, who led the exhumation of the remains in 2012, said earlier this year.

Clues coaxed from the skeleton may shed “a new light” on the physical description of Richard III as a humpbacked man with a “withered arm,” which was used to support history’s evil image of him, Professor Lin Foxhall, head of the University of Leicester’s School of Archaeology and Ancient History, said then.

One immediate discovery was that the skeleton does not have a “withered arm” as depicted by Shakespeare, researchers said.

While not humpbacked, Richard III did suffer from the “severe scoliosis” that appeared to start around the time of puberty, they said.

The king will finally get respect next year.

His remains will be reburied in Leicester Cathedral, close to the site of his original grave.

CNN’s Bryony Jones, Alan Duke and Alden Mahler Levine contributed to this report.