CNN takes you “Inside the Louvre,” building an intimate portrait of a museum like no other. From the handler who looks after the Mona Lisa’s famous smile, to the new director, host Nick Glass meets the people at the heart of Paris’ most renowned institution. Watch the 30-minute special show from Dec 2-4.

Story highlights

Remains of relatives of the woman believed to be the "Mona Lisa" model have been found

Researchers plan to check their DNA against the DNA of a skeleton found at her burial site

If there is a match, they will reconstruct the skeleton's face and compare it to the portrait

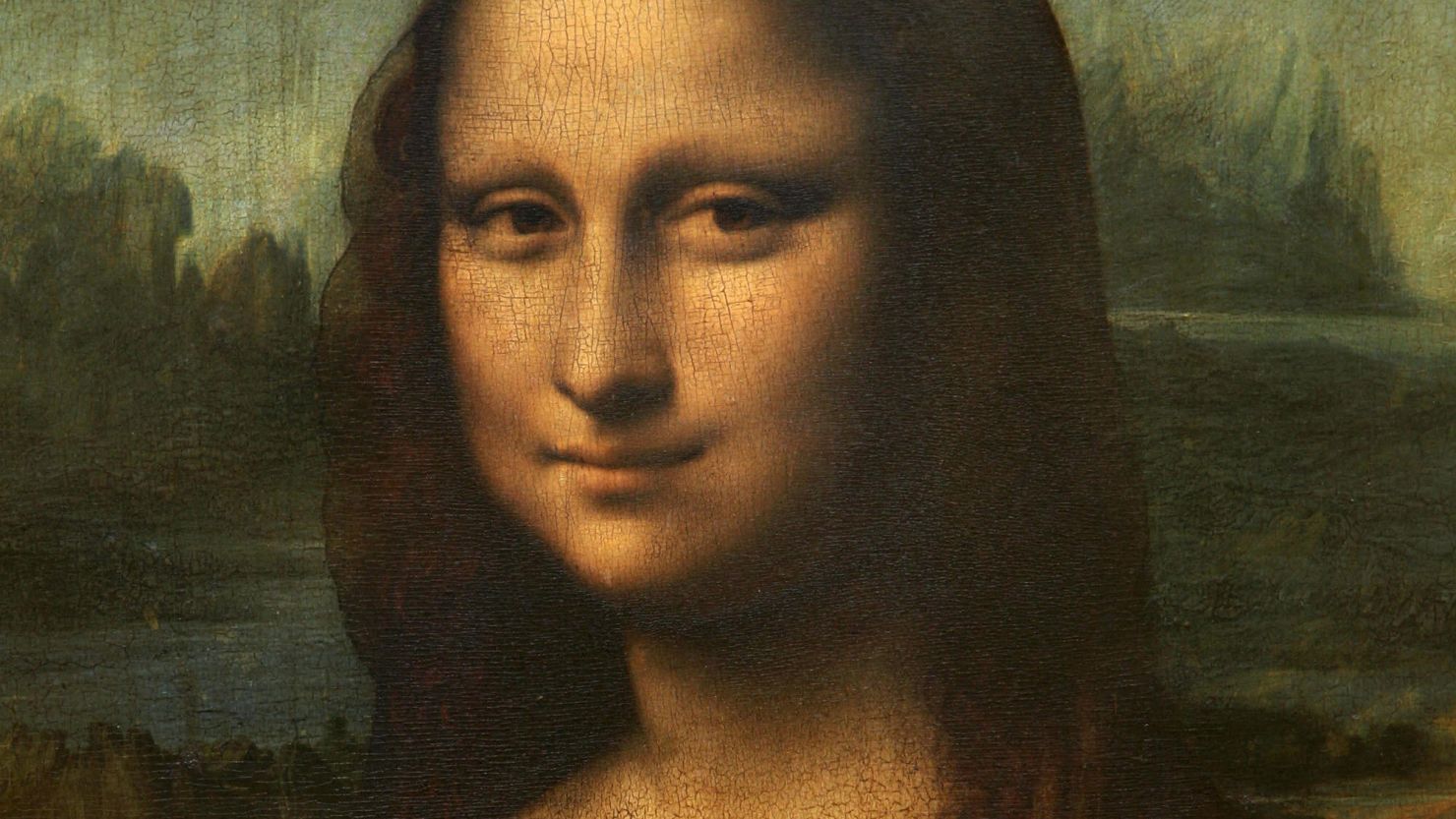

The exhumation of three bodies from a Florentine crypt may have brought Italian researchers a step closer to confirming the identity of the woman believed to be the subject of Leonardo da Vinci’s famous “Mona Lisa” painting, also known as “La Gioconda.”

“La Gioconda” refers to Lisa Gherardini, the second wife of a Florentine silk merchant, Francesco del Giocondo.

The remains of del Giocondo, his son by Gherardini – Piero – and Gherardini’s stepson Bartolomeo have been uncovered in their family crypt, the authority of Florence has announced.

A team led by Silvano Vinceti accessed the remains beneath the Chapel of the Holy Martyrs, in Florence on August 6, it said in a statement.

Last year, Vinceti’s team exhumed the remains of eight women from the ruins of a Franciscan convent in Florence where old city records said Gherardini had been buried.

A laboratory at the University of Bologna had established that three of the skeletons at the St. Ursula convent were consistent with the age at which Gherardini had died, the statement said.

Further carbon testing to establish which of those skeletons dated from the 16th century – when Gherardini died – was being carried out at the University of Salento, it quoted Vinceti as saying.

If DNA taken from the del Giocondo family remains matched one of the skeletons found in the convent ruins, the skeleton could be confirmed as Gherardini’s, he said.

Scientists could then reconstruct Gherardini’s face and compare it to da Vinci’s mysterious portrait.

Talking to CNN’s Ben Wedeman when the convent skeletons were found last year, Vinceti said the reconstruction would have a margin of error of just 2 to 8% – once researchers factored in that Gherardini had probably been in her early 20s when she posed for da Vinci.

Read more: Researchers hope to uncover who’s behind ‘Mona Lisa’ smile

Vinceti told Wedeman he was certain that da Vinci had been commissioned to paint a portrait of Gherardini but could not be sure that the “Mona Lisa” was of her, or just contained some of her features.

For starters, the famous smile was not Gherardini’s, he said. Analysis of the “Mona Lisa” had shown that “when Leonardo began painting the model in front of him, he did not draw that metaphysical, ironic, poignant, elusive smile, but rather he painted a person who was dark and depressed.”

A reconstruction would finally answer the question art historians had been unable to resolve, Vinceti said: “Who was the model for Leonardo?”