Editor’s Note: Stephen Burt is the author of three poetry collections, including “Belmont,” and several critical books, including “Close Calls with Nonsense,” a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award. He is Professor of English at Harvard University and lives in Belmont, Massachusetts. You can find him on Twitter at @accommodatingly.

Story highlights

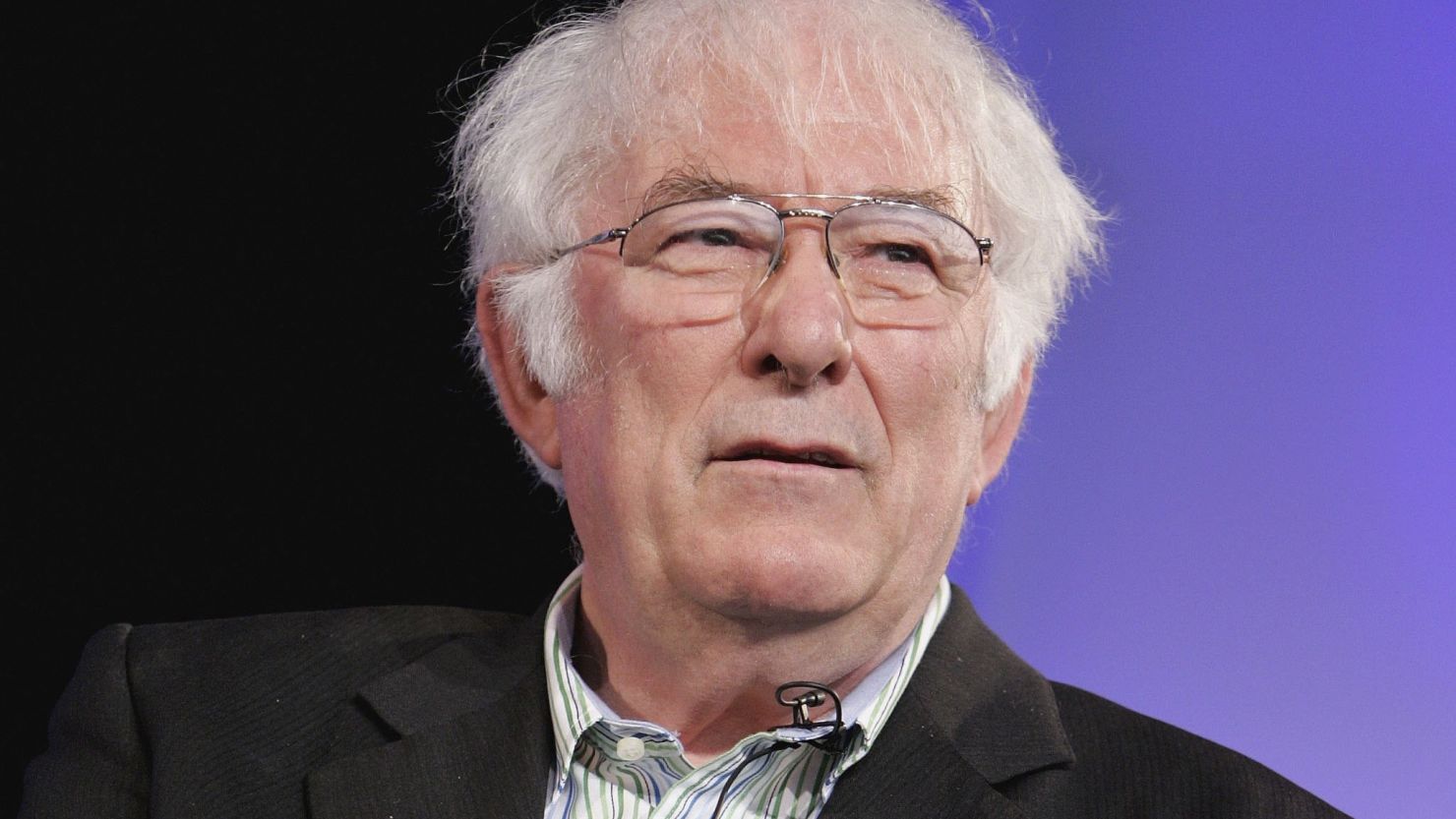

Stephen Burt: Seamus Heaney, who died Friday, wrote poetry, literary essays, translations

His early works were of earth, and of the Troubles; he found fame writing about divided land

He says later he went south, wrote of civic, family life, dead friends, embraced the numinous

Burt: He became perhaps the most popular serious poet writing in English anywhere

Seamus Heaney, the Irish Nobel laureate who died Friday at 74, will be remembered for his translations, for his literary essays, for his generous international public presence, but principally for the poetry he himself wrote. Though the Heaney of the poems could sound unsettled, or even tormented, he was in person equable, welcoming, generous; these qualities would enter the poetry too.

And he will be remembered not for one kind of poetry, but for several: He amazed even attentive admirers as he became, over his long career, in one way the opposite of his early self. His first great poems were tough, inward, tied to the soil; his last, just as Irish, were confident, sometimes gleeful, creatures of air.

Heaney began as a poet of earth. Raised in a large farming family in County Derry, Northern Ireland, educated there and in Belfast, he applied his gifts at first to the landscape where he felt at home, a place of village survivals, of un-English place names (“Broagh,” “Anahorish”) and eloquent modesty, comparing his poetry to ploughing, to blacksmiths’ work.

He wrote in “Bogland”:

Our unfenced country

Is bog that keeps crusting

Between the sights of the sun.

The ground itself is kind, black butter

Melting and opening underfoot.

This kind ground might swallow him up, but it might also provide him with a voice.

When parts of that ground became violent, Heaney was there. His time in Belfast as student and teacher encompassed the violent years known as the Troubles, the years of the UVF and the IRA, of bombings at funerals and British troops on the streets; Heaney became a poet of burial sites, of guilt and self-division in terse, halting stanzas.

In “Wintering Out”(1973) and in “North” (1975), he examined the violence directly and by analogy with the Bronze Age corpses that Danish archaeologists exhumed. “The Grauballe Man,” he wrote, “seems to weep/ the black river of himself” …”with the actual weight/of each hooded victim,/slashed and dumped.”

Those poems made him internationally famous. Had he written nothing else, or nothing as powerful, afterwards, he would be remembered securely as the careful, anguished, self-accusing poet of a divided land.

But he went on; he changed. After “North” he moved south, to pastoral Glanmore, in the Irish Republic. There, with his wife and three children in suburban Dublin, and at Harvard, where Heaney taught for most of the 1980s and 1990s, he would find new and persuasive ways to write about enduring affection, familial and civic, and about how his own spirit could feel more free.

“Glanmore Sonnets,” from “Field Work” (1979), embodies nostalgia along with a pastoral joy:

“Vowels ploughed into other: opened ground,

Each verse returning like the plough turned round.”

(Heaney would use “Opened Ground” as the title for his 1998 Collected Poems.)

Resistant to dogma yet drawn to the numinous, Heaney depicted himself in Station Island (1983) walking a traditional route of Irish Catholic pilgrimage, meeting ghosts from the Irish literary past. One tells him:

“we are earthworms of the earth, and all that/ has gone through us is what will be our trace.”

Another – the ghost of James Joyce – advises him differently:

“The main thing is to write/ for the joy of it … It’s time to swim/ out on your own and fill the element/ with signatures on your own frequency.”

And so he did. Heaney became in his later career a great poet of the spirit lifted, a writer identified with fluency and light, with water and air, as well as with his native ground. One of the twelve-line poems in Seeing Things (1991) remembers the childhood pleasures of wading:

“Sweet transience. Flirt and splash./ Crumpled flow the sky-dipped willows trailed in.”

Another retells the Irish legend of a man who fell out of a magical airborne ship, into a monastery’s scriptorium, then climbed back on board, “Out of the marvelous as he had known it.” Everyday work, even indoor work like writing, could be marvelous too.

Heaney recorded these marvels in sheaves of sonnets, in complex old forms such as sestinas, in an iambic pentameter whose confidence buoyed his readers too, even when – as in his last book, “District and Circle” (2006) – he used those soaring lines to remember dead friends. He became, if book sales are a measure, perhaps the most popular serious poet writing in English anywhere in the world. And he became determinedly international, writing verse parables derived from Eastern Europe, adapting tragic drama from ancient Greece, and translating “Beowulf” from the Anglo-Saxon.

Yet he remained connected to the particulars of the Irish spaces he knew, to his first friends in poetry (and in folk music), and to his own earlier selves.

Later poems (such as “Glanmore Revisited”) would see how he had, and how he had not, changed, and would see – in the 1990s and 2000s – the political change that brought calm, even peace, to the counties of his birth.

“Postscript,” the last poem in “Opened Ground,” begins “in County Clare along the Flaggy Shore”; but it rises soon enough to a space of permission and imagination, a generous space identified with poetry itself, where “You are neither here nor there,/ A hurry through which known and strange things pass/ As big soft buffetings come at the car sideways/ And catch the heart off guard and blow it open.”

Follow @CNNOpinion on Twitter.

Join us at Facebook/CNNOpinion.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Stephen Burt.