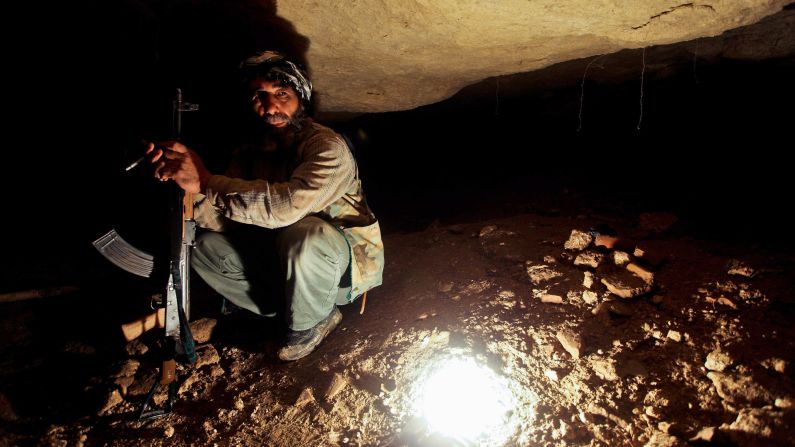

Editor’s Note: Should the West intervene in Syria? Tell us what you think.

Story highlights

Lessons of Iraq pervade dramatic debate in Britain

No two international situations are the same

Be careful of history

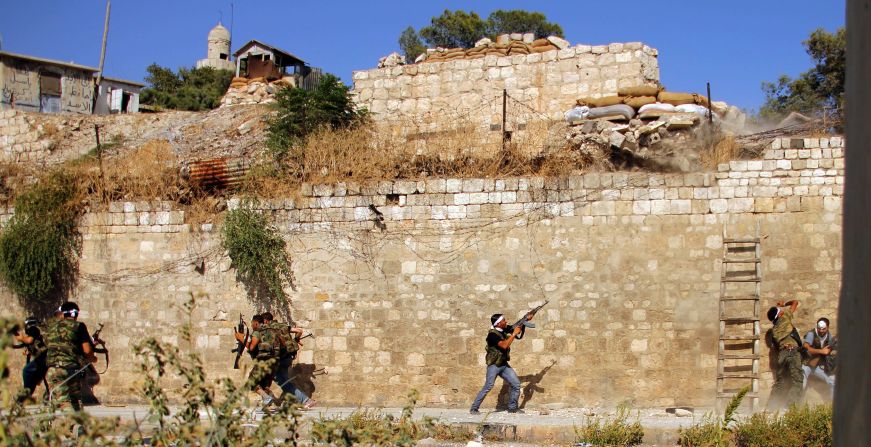

David Cameron must have whiplash. Practically overnight this week, the British prime minister went from being one of the leading voices demanding that Syria’s President Bashar al-Assad be punished for using chemical weapons, to a humbled, chastened politician with his hands tied.

British lawmakers voted Thursday night against even the possibility of using force against Syria, forcing Cameron to concede bluntly, “We will not be taking part in military action.”

What do Syria’s neighbors think?

The vote was close – seven MPs out of the 557 who voted could have changed the result – and the outcome was a shock. Prime ministers aren’t supposed to lose votes on the use of military force. British media said it hadn’t happened in hundreds of years.

But although the result was stunning in one sense, in another it wasn’t surprising.

Over more than seven hours of debate on Syria loomed one chilling specter: Iraq.

Bergen: Syria is a problem from hell for the U.S.

Britain feels badly burned by the way Tony Blair led the country into war there a decade ago, and Cameron was fighting a defensive battle against the memory of Blair from the moment he kicked off debate in the House of Commons: “I’m deeply mindful of the lessons of previous conflicts, in particular the deep concerns of the country of what went wrong in Iraq. We’re not invading a country; we’re not searching for chemical weapons.”

It’s an argument he needed to make.

Why Russia, China, and Iran are standing by Syria

Just a few hours earlier, the speaker of Syria’s Parliament raised the memory of the “dodgy dossier” which Blair’s critics say falsely helped lead Britain to invade Iraq.

And some lawmakers clearly felt burned by the Blair government’s case for war, based on false intelligence.

Even a senior member of Cameron’s own Conservative Party warned Thursday: “We must consider that our intelligence might be wrong because it has been before.

“And we must be very hard on testing it,” David Davis said.

Does the public care about U.N. support?

“We cannot ignore the calamitous lessons of the Iraq war,” said Angus Robertson of the Scottish National Party, who opposed action in Syria.

That’s a very normal human response – so common that there are cliches about it, like “once bitten, twice shy,” and “fool me once, shame on you; fool me twice, shame on me.”

It’s also the wrong response. Syria is not Iraq. It’s not Libya or Serbia or Nazi Germany.

Syria is Syria.

Be careful in trying to follow history

Tempting as it is to base policy decisions on past experience, it’s dangerous. No two situations are the same.

And yet politicians and pundits, generals and journalists do it all the time.

Traumatized by the image of U.S. troops being dragged dead through the streets of Mogadishu, Somalia, in 1993, Washington declined to intervene in the mass killings in Rwanda a year later.

With those hundreds of thousands of deaths fresh in its memory, the West did intervene in Bosnia when concentration camp-style images suggested that genocide was going on there.

Any of those decisions could have been right or wrong on their own merits – the critical thing is that they must have been made on their own merits.

Somalia is not Rwanda. Neither one is Bosnia. Iraq is not Afghanistan.

For that matter, David Cameron is not Tony Blair and Barack Obama is not George W. Bush.

Difficult as it may be, policymakers must not rely on historical examples because every case is unique.

It’s intellectually dishonest to say the West shouldn’t bomb Syria because Iraq had no weapons of mass destruction; it’s naive to say it should bomb because bombing Libya helped dislodge Muammar Gadhafi.

Syrian evidence and policy must be considered solely on their own merits.

The story of the boy who cried wolf is a caution not to raise false alarms, but it also contains an admonishment for the villagers who didn’t check the facts when it turned out there really was a wolf.

As usual, Mark Twain put it best: “We should be careful to get out of an experience only the wisdom that is in it and stop there, lest we be like the cat that sits down on a hot stove lid. She will never sit down on a hot stove lid again and that is well but also she will never sit down on a cold one anymore.”