Editor’s Note: Leading Women connects you to extraordinary women of our time. Each month, we meet two women at the top of their field, exploring their careers, lives and ideas.

Story highlights

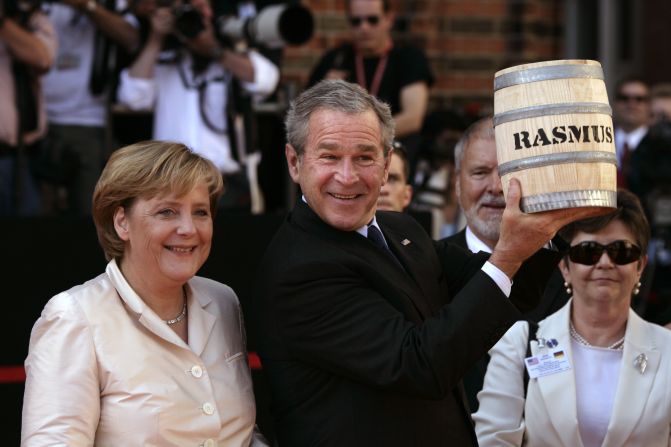

Merkel wins third term as German Chancellor after elections on Sunday

Despite being described as frugal, cold and boring, Forbes named Merkel world's most powerful female in May

Merkel's scientific background means she tackles problems in a calm, analytical manner

Frugal, cold and boring – those are just some of the words Germany’s chancellor Angela Merkel has been called by her peers and the global press days before the German election.

So how did a quiet, unassuming fraulein from a small, rural town in the former communist-ruled German Democratic Republic (GDR) become arguably the most powerful female politician of all time?

While the constant chatter of fixing the Eurozone has recently abated, the Christian Democratic Union leader was a popular choice for another term with strong approval ratings thanks to securing the country’s lowest unemployment rate in two decades.

Upon completion of her recently won third term as chancellor, by 2016 she will become the longest-serving elected female head of government in history. The original “Iron Lady” Margaret Thatcher, who served Britain for 11 years as prime minister, currently holds this record.

Merkel’s rise from political obscurity to the highest publicly elected office in Germany is a captivating tale. Born in West Germany, her father Horst Kasner, a Lutheran pastor moved the family in 1957 to the small town of Templin in East Germany shortly before the erection of the Berlin Wall.

Humble beginnings

Growing up under communist rule in East Germany would have had a strong impact on the future chancellor. While she has often said she was never interested in the politics of the new state, her world view was shaped by her surroundings. The restrictions and ever-present secret police – the Stasi – taught Merkel the importance of discretion and when to speak up.

Through her childhood, Merkel was strong academically and teachers praised her skills in math and language, but it was the sciences that caught her attention. In turn, she went on to study physics at the University of Leipzig. The characteristics that come from being a scientist have become one of her defining skills as a politician.

As Stefan Kornelius writes in Merkel’s authorized biography, “Angela Merkel – The Chancellor and Her World”: “Merkel shapes her world view in an analytical way. She weighs up arguments, industriously collects facts, considers the pros and cons …

“She admires people with qualities that are not her own, but prefers to work her way steadily forward. Herein lies Merkel’s problem: if her opponent doesn’t use rational arguments, then the logical framework ceases to function, arguments cannot be weighted against each other and compromises cannot be reached.”

Deja vu?

Upon leaving university and earning her PhD, Merkel initially worked as a quantum chemist at the Academy of Sciences in East Berlin before joining the a small independent party, Democatic Awakening shortly before reunification between East and West Germany.

She swiftly rose through the ranks of the party, which quickly aligned with then-chancellor of West Germany Helmut Kolhl.

By the time the Berlin Wall fell in October of 1990, Merkel was working as deputy press secretary to the East German premier. In the following months, she watched diplomacy in action and the rapid financial collapse of East Germany after reunification. Put simply, this experience shaped her economic world view forever.

“Look, I’ve experienced the collapse of a country, the GDR,” she said in April at an event with the Polish Prime Minister, Donald Tusk. “The economic system failed under the aegis of the Soviet Union.

“What I really don’t want is to look on, eyes open, as Europe as a whole slips back. I would find that absurd, we have all the skills in our hands.”

Read: Merkel – A woman of power

Unafraid to say ‘nein’

Viewed as the de facto leader of Europe, Merkel’s legacy will largely be determined by the outcome of the euro crisis. Thrust into the center of Europe’s ailing economic landscape, she has taken a hard line with neighboring countries and world leaders.

“In the debt crisis, Merkel is seen as the hard-bitten, humorless, austerity-enforcing “Madame Non” who refuses to underwrite the rest of the euro area’s debt,” writes journalists Alan Crawford and Tony Czuczka in their recent book, Angela Merkel: A Chancellorship Forged in Crisis.

Bringing her own brand of Germany’s social market economy to the world stage with her divisive austerity measures, Merkel operates a step-by-step approach to her politics.

As Crawford and Czuczka write: “… Merkel consults widely to better formulate her approach to policy making. She is not given to snap, intuitive decisions, but is rather very deliberate in the way she reaches her conclusions.”

But what also makes Merkel most unusual is how little her lifestyle has changed since assuming power. In contrast to fellow politicians, she lives a modest way of life residing in her Berlin apartment with her second husband Joachim Sauerspends.

What’s more, she doesn’t put on lavish displays when hosting world leaders and she continues to spend weekends away from public glare at her home in the rural hamlet of Hohenwalde, east of Berlin.

Though she is often described as “boring” and has been known to give long press conferences without revealing anything of news value, her understated political persona is her strength.

In an age where pomp and performance can seem to trump policy and substance, Merkel is the exception to the rule. Her shrewd negotiation skills and ability to deliver make up for what she lacks in charm and charisma. After all, sometimes the ability for a leader to govern is more important than the ability to warm a crowd.