Story highlights

Golden Dawn emerged as a political force during Greece's 2012 elections

But now, its MPs have been arrested on suspicion of running a criminal organization

The arrests come after a left-wing hip-hop artist was stabbed by an alleged sympathizer

The party's rise came amid harsh economic climate in which many Greeks have suffered

They raise their arms in a fascist salute, waving flags in a show of fervent national pride. It is a scene reminiscent of Nazi Germany but this is the Golden Dawn party faithful, and they’re in a far more modern setting: Greece, the cradle of democracy.

Golden Dawn’s firebrand leader, Nikos Michaloliakos, captured the fury of an exhausted constituency and won his party 7% of the vote in the last Greek elections.

Now, just over a year later, he is in jail after being accused of running a criminal organization following the violent death of a left-wing hip-hop artist.

Golden Dawn’s emergence as a political force was in part a reaction against the political duopoly that had ruled Greece for decades. But other factors, similar to those which have fed the rise of other right-wing movements, played into Golden Dawn’s success.

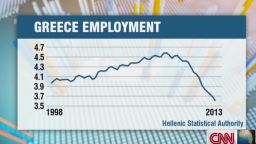

Greece, the weakest member of the eurozone, has suffered harsh austerity measures, a grinding recession and unemployment levels which are now near 30%. It is also the favored gateway for illegal immigrants into Europe, given its long coastlines and geographical position.

Golden Dawn, which campaigns on the creation of a nationalist state and has a logo echoing the swastika, found itself a niche.

It had tapped into the fear of a country overwhelmed by financial crisis and unable to cope with the flood of immigrants across its borders.

In the space of three years, Golden Dawn went from a fringe party, polling at just 0.3%, to one which won 18 of the Greek parliament’s 300 seats. Its support then soared into double digits, allowing it to claim the title of Greece’s third biggest political player.

Golden Dawn, along with the left-wing coalition Syriza, had disrupted the country’s cosy political landscape, where power had been traded between the center-left Pasok and center-right New Democracy since the restoration of democracy in 1974.

And, as the country’s economy contracted, government implemented cutbacks, layoffs rose and the Arab Spring fed an increase in immigration, more Greeks found solace in the party’s extreme rhetoric. Its influence grew.

The party’s volatile membership

But Golden Dawn’s members soon proved volatile, attracting headlines for their extreme behavior and violence, particularly against immigrants.

In June last year, the party’s spokesman, Ilias Kasidiaris, clashed with two left-wing politicians on live television before going on the run.

Kasidiaris, during a television panel, threw a glass of water at Rena Dourou, a member of Syriza, after she suggested his party would take the country back “500 years” if they came to power. He then turned on Liana Kanelli, part of the Communist Party of Greece, and slapped her in the face.

Human Rights Watch, which called the party “unabashedly neo-fascist” documented attacks it said were linked to Golden Dawn members. It noted other members, including Michaloliakos’ daughter, were questioned in connection to violence against immigrants.

The Human Rights Watch report also pointed to the party’s calls for anti-personnel landmines along the Greece-Turkey border in the Evros region, which is a common crossing for immigrants into Europe.

Golden Dawn members deny being involved in violence. Michaloliakos reportedly told the courts he condemned any form of violence while others, such as Roberto Chaidi, who spoke to CNN in January, said the party was defending the country.

However in an interview with the BBC Ilias Panagiotaros, a Golden Dawn MP, said: “Greek society is ready to have a fight, a new type of civil war.

“On the one side there will be, let’s say, nationalists like us and …Greeks who want our country to be as it used to be. And on the other on side there will be illegal immigrants and …all those who have destroyed Athens several times in Greece.”

Golden Dawn representatives declined to comment to CNN for this story.

But the party’s popularity remained high, even as accusations of its violence grew.

Then, last month, left-wing hip-hop musician Pavlos Fyssas, a popular anti-fascist figure with the stage name Killah P, was stabbed to death on an Athens street after a brawl that broke out over a football game.

Police arrested George Roupakias, a 45-year-old Golden Dawn sympathizer, and charged him with voluntary manslaughter.

His death triggered fury, and police moved against the party.

Political party or criminal gang?

In an unprecedented crackdown, police arrested more than 20 members of Golden Dawn, including party leader Michaloliakos and five other parliamentarians, on charges ranging from founding and participating in a criminal gang to blackmail, assault, and murder.

Prosecutors are also seeking to widen the net by asking parliamentary immunity on other Golden Dawn MPs be lifted.

It is the first time since 1974, after a seven-year military junta, that a party leader and serving members of parliament have been arrested.

Michaloliakos remains in custody while three other Golden Dawn lawmakers who have already appeared in court – Ilias Kasidiaris, Ilias Panagiotaros and Nikos Mihos – have been released pending trial. A fourth, Ioannis Lagos, also remains in custody.

The party’s second-in-command, Christos Pappas, who turned himself in saying he had nothing to hide, has also been remanded.

Police released images of the collection of Nazi paraphernalia, including a picture of Adolf Hitler with Golden Dawn written on it, Fuhrer-branded wine bottles, guns and weapons discovered at his house. At Michaloliakos’ house, police found weapons, ammunition and 43,100 euros cash.

The party has denied involvement in Fyssas’ death, with Kasidiaris, in a public statement, calling it a “heinous crime.”

Police say Roupakias confessed to the killing after he was arrested, and admitted he had links with Golden Dawn. His phone records are now being examined to see how strong those links are.

As investigations continue, there have been calls to ban Golden Dawn, whose support has dropped, according to a poll in Sunday’s Proto Thema newspaper, from 10.8% in June to 6.4%.

The arrested lawmakers will retain their parliamentary seats unless they are convicted of a crime. On September 30, the government also submitted a draft law that, if voted in, would suspend state funding for a party if any of its leadership or MPs were being prosecuted for a felony.

The sudden police move against Golden Dawn has, meanwhile, raised questions about whether it has links with authorities and allegations of violence against immigrants, which critics say have never been properly investigated.

Nick Malkoutzis, a contributor to independent political and economic website MacroPolis, said “Greece’s authorities have also shown a remarkable tolerance to this extremism.”

Malkoutzis said there had been a failure to clamp down on the party’s “violent and abusive behavior,” allowing it to flourish. It took the murder of a “young, charismatic musician” to force the authorities’ hand, Malkoutzis said.

A Hellenic Police representative told CNN on email, translated from Greek, that the force – as a state institution – “should not have any links with any political orientation.” However, cases that arise are examined individually, the statement said, and Greece’s Ministry of Public Order aims not to have any “shadows” over the police.

Further, the police investigate reported violence but such cases were complex and took time, the email said. The ensuing delays “might lead to wrong conclusions.”

Public Order Minister Nikos Dendias also told CNN’s Christiane Amanpour the country was determined to rid its police of “any racist elements.”

What does Golden Dawn stand for?

Golden Dawn was founded during the early 1980s by Michaloliakos, who was born in 1957. Its website describes how Michaloliakos studied mathematics at Athens University, before becoming involved in nationalist politics aged 16.

Michaloliakos was arrested in 1974 after demonstrating against the British during the Turkish invasion of Cyprus, the party website says.

It was not the last time Michaloliakos would find himself on the wrong side of the law. In 1979, according to Vassiliki Georgiadou, an Associate Professor of Political Science at Athens’ Panteion University, Michaloliakos was sentenced to 13 months for “possession of explosives, after being linked to extremist activities.”

In an interview with Human Rights Watch, Michaloliakos said he wanted Greece to “belong to the Greeks.” Further, he said, the party members were “proud to be Greek,” and wanted to “save our national identity, our thousands-year history. If that means we are racist, then yes we are.”

Chaidi, during the January interview with CNN, echoed those comments, saying: “If fighting for my nation means that I get to be called a Nazi and a racist … then I am.”

Michaloliakos has publicly voiced his sympathies with the country’s junta leaders, whom Malkoutzis said the Golden Dawn leader met while in prison.

And the links remained strong: According to Dimitris Psarras, author of 2012’s “The Black Bible of Golden Dawn,” Michaloliakos was appointed leader of the former dictator Georgios Papadopoulos’ party EPEN in 1984, before he focused his attention on the then-embryonic Golden Dawn.

The party was founded to “promote Nazi ideology,” and “never stopped believing in racism and anti-Semitism,” Psarras told CNN in an email.

Matthew Feldman, an expert in fascist ideology from Teesside University, told CNN he believed the party was “very” extreme, as reflected in its swastika-like insignia, paramilitarism and allegations of violence.

“Very few analysts have difficulty seeing this as an extreme right wing – not just “radical right,” or “far-right” – organization,” he said. “Many would also agree with me that this is ultimately a revolutionary, neo-fascist party.”

Academic views differ over whether the party can be categorized as neo-Nazi. Feldman said he would be hesitant about putting Golden Dawn in that category given the historic pain inflicted on Greece by the Germans during its occupation in WWII. Its history, he said, would make such sympathies anathema to a nationalist movement.

However Cas Mudde, assistant professor in the School of Public and International Affairs of the University of Georgia, said he regarded Golden Dawn as one of the “few truly neo-Nazi parties in Europe,” as evidenced by party literature and Nazi materials.

“Golden Dawn is not looking so much to the Greek junta for inspiration, but rather to Nazi Germany,” Mudde told CNN in email.

Golden Dawn has denied being a neo-Nazi party, although Michaloliakos, in an interview with a Greek TV channel May last year, said “there were no gas chambers” in Auschwitz.

Greek’s volatile atmosphere

Greece tripped the eurozone’s crisis in 2010, after revealing its deficit was four times bigger than it had previously reported.

It was the first of the eurozone countries to be bailed out, before it stumbled into the arms of its international creditors for a second time a year later. Despite implementing austerity measures in return for bailout funds, the country’s economy continued to struggle and unemployment rose. A third package of aid is now expected.

The country’s youth, in particular, have suffered as jobs dried up. Despite the cultural pull of family and homeland, many have left in search of work and stability. Some previously interviewed by CNN have told how they have struggled to get by on wages that have been cut while costs have risen.

For those who become marginalized by such an environment, political extremism can exert a pull. According to Psarras, Golden Dawn supporters are those who “think of nothing but revenge. We are talking about people who no longer believe in anything.”

The perfect storm of economic pain and political discontent has also created an atmosphere many have compared to that in Weimar, Germany, which led to the rise of the Nazi party.

However, Feldman said while there were some “troubling parallels,” the circumstances – such as the size of two countries, the existence of democracy in Greece and the size of the extremist parties – were different.

“However bad the Great Recession has been,” Feldman said, it “is not the same as millions of dead soldiers across Europe calling out, from beyond the grave, to have their sacrifices justified.”