Story highlights

"We have made progress since 1990, but we have not made sufficient progress," she says

The human rights activist spent years under house arrest

She won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1991

"If we were all perfect, I think it would be a very boring world," she says in acceptance speech

Better late than never.

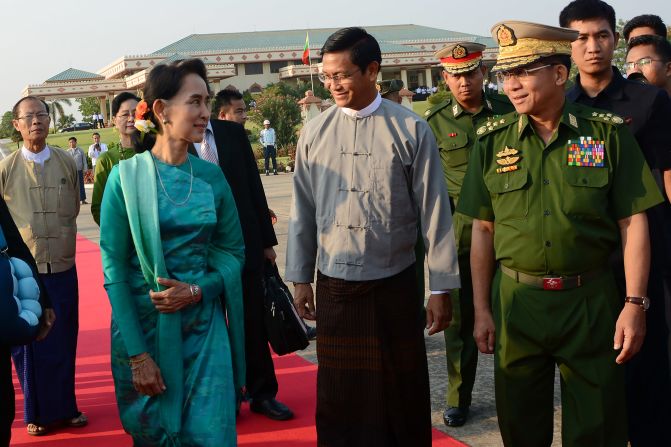

Twenty-three years after being awarded the Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought, Myanmar militant and parliamentary opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi collected it Tuesday from the European Parliament in Strasbourg, France, but said she still has more work to do.

“We have made progress since 1990, but we have not made sufficient progress,” said the former longtime political prisoner, who was freed in 2010 after years of house arrest.

From Burma to Myanmar: The land of rising expectations

Suu Kyi’s award comes as Myanmar, sometimes referred to as Burma, is emerging from decades of authoritarian military rule that resulted in internal oppression and international isolation.

President Thein Sein, a former military official, has overseen the introduction of greater political freedoms, peace talks with ethnic rebels and the successful participation of Suu Kyi and her party in legislative elections.

Suu Kyi: ‘I want to run for president’

“Our people are just beginning to learn that freedom of thought is possible, but we want to make sure that the right to think freely and to live in accordance with a conscience has to be preserved,” she told the international body, which gave her a standing ovation that lasted more than a minute.

“This right is not yet guaranteed 100%. We still have to work very hard before the basic law of the land, which is the constitution, will guarantee us the right to live in accordance with our conscience. That is why we insist that the present constitution must be changed to be a truly democratic one.”

The changes the 68-year-old politician is seeking include one that would let her run for president.

Read more: Miracles in Suu Kyi’s garden

She is ineligible to contest the presidency because of a clause that bans anyone with a foreign spouse or child. Suu Kyi’s late husband, Michael Aris, was English and her two sons have British passports.

Suu Kyi praised Andrei Sakharov, the Soviet nuclear physicist and human rights activist after whom the prize is named. Sakharov, who died in 1989, was “a great champion of human rights and freedom of thought,” she said.

She cited the latter as essential to human progress. “Freedom of thought begins with the right to ask questions,” she said. “Many of our people were arrested almost on a daily basis, and we had to teach them to ask those who came to arrest them – Why? We had to teach them their basic rights and we had to say to them, if somebody comes to arrest you in the middle of the night, you have the right to ask: Do you have a warrant? Even that, many of our people did not know.”

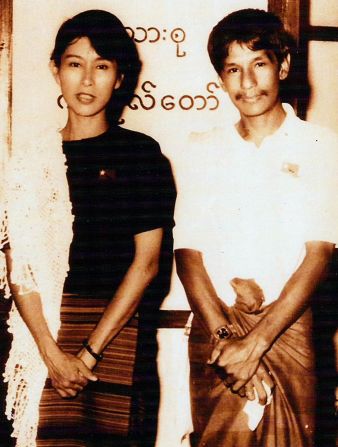

Suu Kyi’s father, Gen. Aung San, was a hero of Burmese independence who went on to found Burma’s military before his death in 1947; his daughter spent much of her early life abroad, going to school in India and at Oxford University in England.

Leadership was bestowed upon her when she returned home in 1988 after her mother suffered a stroke.

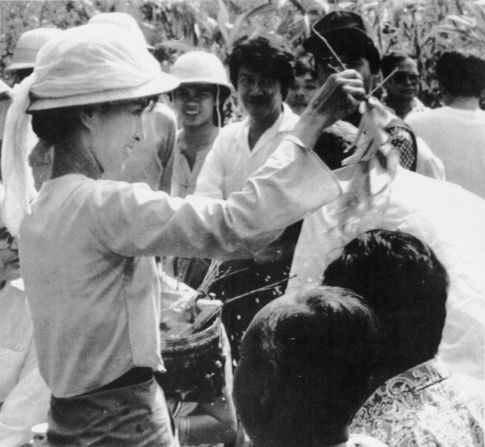

During her visit, a student uprising erupted and spotlighted her as a symbol of freedom. When Suu Kyi’s mother died the next year, Suu Kyi vowed that just as her parents had served the people of Burma, so, too, would she.

In her first public speech, she stood before a crowd of several hundred thousand people with her husband and her two sons and called for a democratic government.

She won over the Burmese people, but not the military regime, which threw her in jail in 1989.

But even with Suu Kyi behind bars, her National League for Democracy party won the country’s first democratic elections in more than two decades the following year by a landslide, gaining 82% of the contested seats in parliament.

The regime ignored the results of the vote and Senior Gen. Than Shwe continued to impose numerous terms of house arrest on her.

Suu Kyi, who last March won re-election as Myanmar’s leader of the National League for Democracy, noted that the year she won the prize was the year when Myanmar had held its first democratic elections in more than two decades.

“But we were never allowed to take office, we were never allowed to even call parliament,” she recalled Tuesday. “Instead, our party was oppressed, our people were persecuted and we had to struggle on for a couple more decades before we have come to this stage.”

She added that a primary aim of the country’s democratic movement is to bring about reconciliation, including between the army and the pro-democracy movement, and she called on world opinion to help.

In the age of globalization, “the weight of international opinion is immense,” she said. “Nowhere in the world can people ignore what other people think.”

Though no system is perfect, even democracy, “I think there is something nice and challenging about imperfection,” she said. “If we were all perfect, I think it would be a very boring world.”

CNN’s Moni Basu contributed to this report.