Story highlights

About 6,000 Western tourists have visited North Korea this year, says North Korea travel company Koryo Tours

North Korea visitors are given a strict set of guidelines to follow

Outside the hotel, a guide accompanies visitors at all times and every tour is a carefully choreographed affair

The tour bus bounces along one of North Korea’s potholed roads, pop music blasting out over the speakers. It’s a catchy tune and even though none of the tourists can understand the lyrics, a few are tapping their feet to the beat.

The hit song, “Without a Break,” is by Moranbong, by far North Korea’s most popular band. The driver is clearly a fan and plays the DVD several times a day.

Most tourists are busy looking out the window and pay little attention to the video screened at the front of the bus. They don’t notice the nuclear missile being launched behind the all-girl band, nor do they see it smash into our little blue planet, blowing up the Earth.

“‘Without a Break’ is about the nuclear destruction of the U.S.,” says Australian Mark Freeman, who has visited North Korea four times.

“Tourists dance to it because they don’t know the lyrics, they don’t know what the song is about.”

Travel to North Korea raises a number of sticky issues, not least of all the ethical issue of supporting a repressive regime. For those who opt to go, it’s an opportunity to glimpse one of the most isolated, unfathomable and feared countries in the world.

“There have been about 6,000 Western tourists this year – that’s a tenfold increase on a decade ago,” says Koryo Tours general manager Simon Cockerell.

Photos North Korea didn't want you to see

But when you sign up to visit the DPRK you have to play by their rules.

There are strict guidelines in place about what you can and cannot do. Break with the protocol – or even be suspected of it – and not just you but the rest of your group will be sent back early. Or worse, as U.S. military veteran Merrill Newman discovered.

According to his family, the Palo Alto, California, resident had gone on a 10-day organized private tour of North Korea in October. From phone calls and postcards he sent, the trip was going well and there was no indication of any kind of problem, son Jeff Newman said.

The day before he was to leave, “one or two Korean authorities” met with Newman and his tour guide, the son added. They talked about Newman’s service record, which left “my dad … a bit bothered,” according to Jeff Newman.

Then, just minutes before his Beijing-bound plane was set to depart Pyongyang in late October, he was taken off the aircraft by North Korean authorities.

More: U.S. ‘deeply concerned’ about citizens held in North Korea, including Newman

Getting into North Korea

Unless you’re invited as part of a business delegation, the only way to visit North Korea is by joining a tour. Depending on the number of tourists and whether or not it includes Americans, two to three trained guides-cum-minders accompany each group.

Aside from the hotels where tourists can roam freely between their room, the bar and the restaurant, a guide accompanies visitors at all times.

The guides are friendly and accommodating. They go out of their way to keep their charges happy – singing songs and ensuring there is plenty to eat and drink. The lavish meals, with a big spread put out for every meal, is all part of the package. The DPRK wants Westerners to return home raving about how much they were given to eat.

American Kent Rutter, a lawyer, has visited North Korea twice and says he liked the guides and asked plenty of questions, but was frustrated when he didn’t get a straight answer.

“Their job was to tell us whatever the government wanted us to hear, even if it contradicted what we could see from the bus window,” he says.

More: Touring North Korea: What’s real, what’s fake?

Florian Seidel, a German localization expert for a computer game company in Japan, says he got a lot more out of his second trip to North Korea because he had a better grasp of what was going on. He did some research – mostly online, reading blogs and scouring Google Earth images – ahead of his second visit to the remote North East of the country and was wise on what to look out for in the region.

“Don’t worry about being lied to, worry about not getting the interesting information,” says Seidel.

“Guides repeat certain random things a dozen times, but when you drive right past the entrance to a concentration camp they won’t tell you.”

If you don’t want to bow, stay home

A key aspect of any trip to North Korea is the need to show reverence for past and present leaders. This means not only referring to them with respect, but also bowing in front of the statues of Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il.

Pyongyang has a number of statues, so this can mean laying flowers and bowing several times on a week-long trip. For those traveling around the country, there’s a Kim Il Sung statue in every city.

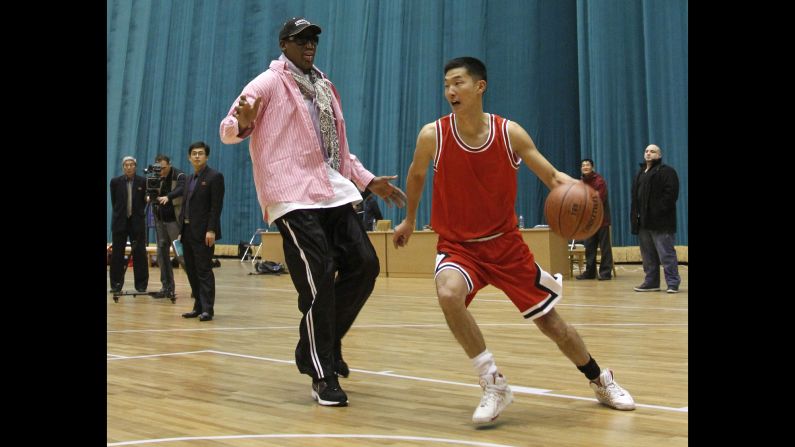

Dennis Rodman's trips to North Korea

Koryo Tours, the longest running and most specialized travel company for the DPRK, advises tourists in their briefing notes that they will be expected to bow in front of the statues and warns: “If you are not willing to behave at some points as expected by the local customs then we recommend you do not visit the DPRK, the potential for offense to be taken by the hosts which then adversely affects the tour is too great.”

German tourist Seidel didn’t enjoy the obligatory bowing but understood that it was a necessary part of being allowed to visit.

“I felt like an atheist during Holy Mass – I couldn’t relate, but I played along to avoid offending anybody,” he says.

Repeat visitors to the DPRK quickly realize that the best way to get the most out of a trip is to stick to the rules. There’s little point grilling the guides about politics or gulags because you won’t get a straight answer.

Every tour is a carefully choreographed affair, designed to show the country in its best light, but much can gleaned on the drive between approved tourists sites.

It’s especially interesting when unexpected events force a sudden change of plan. Australian tourist Freeman was on a tour of the north east when road works meant the bus had to take a side road through an old village.

“The guides got very flustered because all of a sudden they couldn’t use the road they knew was safe for us to travel,” says Freeman.

“They even got off the bus and tried to reason with the construction guys, they were incredibly nervous.”

More: Behind the veil: Rare look at life in North Korea

He compares a tour of the DPRK to the film “The Matrix.” The occasional glitches in the tour, say when the bus breaks down and is forced to make an impromptu stop, are like the scene in the film when the cat walks through twice – a crack in the Matrix.

So long as you don’t break the rules – disrespect the leaders, wander off on your own, try to speak to the locals without permission – then North Korea is a very safe place to visit.

Haydon Howlett, a New Zealand tourist who visited Pyonyang for the first time this summer, says it’s one of the safest places he’s ever visited.

“There aren’t many countries where you can leave your bag loaded with cash, cameras and passports and know that it’ll be there when you return,” says Howlett.

Travel blogger Earl weighed up the pros and cons of visiting on his site, www.wanderingearl.com. The reasons for not going were fairly convincing: money from the tour would support the regime and it’s repressive policies; foreigners are used as propaganda tools by the North Korean government by presenting tourists as people who come to pay their respects to the regime and leaders; it would be a controlled and limited experience; and there would be little interaction with North Koreans.

But in the end he decided to go and didn’t regret his decision.

“I still believe that the benefits of traveling to North Korea do indeed outweigh the negatives,” he wrote on his blog.

It’s quite possible to visit North Korea and buy into the vision of the country that’s offered, without question. Many do. Freeman was stunned by two young Australian women who announced at the end of their week-long tour that they were going to tell everyone back home that North Korea was nothing like what the media portrays.

“They were so na?ve,” says Freeman.

Had they forgotten that there are 300,000 plus people who are going to die in concentration camps? They aren’t called Death Camps because people are executed there, they are called Death Camps because you stay there until you die.”

More: Gallery: Unseen face of Pyongyang

CNN’s Greg Botelho contributed to this report.