Story highlights

"He did not die from a natural death," Suha Arafat said Tuesday

She says the findings by French scientists contract those of Swiss scientists

The French findings conclude Yasser Arafat was not poisoned with polonium-210

Last month, Swiss scientists said there was evidence of polonium in samples

Yasser Arafat’s widow on Tuesday questioned the findings of French scientists that the Palestinian leader did not die from radioactive polonium poisoning but rather from natural causes.

The conclusion, leaked to multiple French media agencies and Reuters, contradicts the findings of Swiss forensic scientists who concluded last month that samples taken from Arafat’s exhumed body were consistent with polonium-210 exposure but did not definitely prove that he was poisoned.

“I’m convinced there is something wrong, and he did not die from a natural death,” Suha Arafat said at a news conference in Paris.

She said she is requesting that the Swiss findings be made available to French authorities investigating her husband’s death. She said the medical experts in Switzerland and France came from different medical fields.

“I don’t doubt them. But they are different skills. They are different types of medicines,” she said.

The French findings will do little to quell the rumors that Arafat was poisoned.

Arafat died at age 75 at a Paris military hospital in November 2004 after he had a brain hemorrhage and slipped into a coma. Palestinian officials said in the days before his death that Arafat had a blood disorder – though they ruled out leukemia – and that he had digestive problems.

Rumors of poisoning circulated at the time, but Palestinian officials denied them.

Two weeks after Arafat’s death, his nephew said medical records showed no cause of death. Nasser al-Kidwa, who was the Palestinian observer to the United Nations, said toxicology tests showed “no known poison,” though he refused to exclude the possibility that poison caused his uncle’s death.

Polonium-210 made headlines in 2006, when it was used to kill Alexander Litvinenko, a former KGB agent who came to Britain in 2000 after turning whistle-blower on the FSB, the KGB’s successor.

In a deathbed statement from a London hospital, Litvinenko blamed Russia’s President Vladimir Putin, an accusation the Kremlin strongly denied.

Palestinians who view Arafat as a symbol of resistance are also quite emotional about the suspicion he was poisoned.

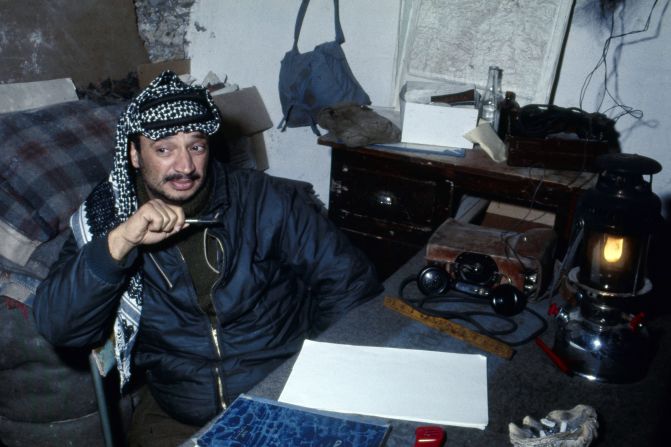

Arafat first led the Palestine Liberation Organization, which carried out attacks against Israeli targets, and then served as the leader of the quasi-governmental Palestinian Authority after parts of the West Bank and Gaza were returned to Palestinian control.

He was considered one of the pioneers of what became known as “television terrorism,” high-profile attacks that targeted Israelis and made for big television stories.

Arafat won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1994, along with Israeli leaders Yitzhak Rabin and Shimon Peres, for their work on the Oslo accords in 1993. The Oslo agreement was perceived at the time as a breakthrough that could lead to an independent Palestinian state and a permanent peace with Israel.

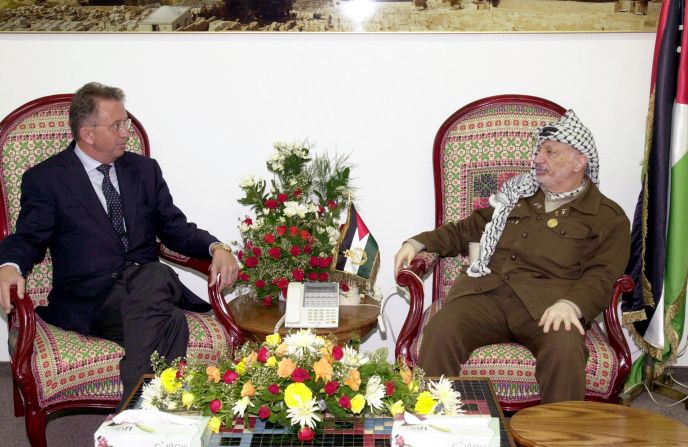

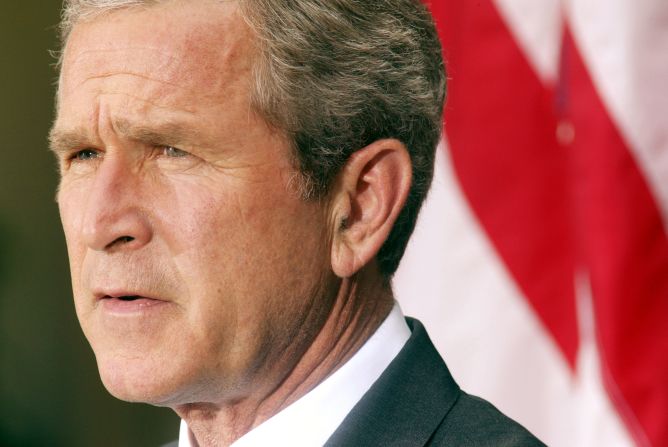

But in 2000, Arafat rejected an Israeli peace deal based on the Oslo deal. That led to a Palestinian uprising that lasted more than four years. Israel – in retaliation for increased terror attacks on Israelis – severely restricted Arafat’s movements, confining him to his West Bank compound in Ramallah in December 2001.

Sandrine Amiel reported from Paris, and Chelsea J. Carter wrote and reported from Atlanta.