Story highlights

Family, friends of Ronnie Biggs tell his publisher he died early Wednesday

Biggs became notorious for his role in a 1963 heist known as the "Great Train Robbery"

After escaping from prison, he went on the run, living as a celebrity fugitive in Brazil

He returned to Britain in 2001, broke and ailing, and spent several more years in prison

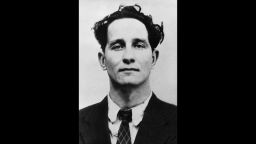

“Great Train Robber” Ronnie Biggs – one of the most notorious British criminals of the 20th century – has died, his publisher told CNN on Wednesday. He was 84.

Biggs, who despite his crimes became the subject of books, films and TV shows and even recorded a single with the Sex Pistols, had been released from prison in 2009 on health grounds.

Cliff Moulder, of publisher MPress, told CNN that close family and friends informed him that Biggs passed away early Wednesday. Moulder published Biggs’ most recent books, “Odd Man Out: The Last Straw,” and “The Great Train Robbery – 50th Anniversary Special.”

Biggs earned his nickname from that train robbery, an infamous 1963 heist dubbed the “crime of the century.” It was an act that transformed him from a petty London thief into one of the most wanted men in Britain.

Biggs and 14 other professional criminals made off with the equivalent of 2.5 million pounds in used bank notes – an amount that would equal tens of millions today.

The thieves held up a mail train from Glasgow to London early in the morning. In the course of the robbery, the train driver was badly beaten with an iron bar.

Most of the gang, including Biggs, were soon picked up in a massive manhunt after police discovered fingerprints at a farmhouse hideout where the robbers had holed up to split their spoils.

Biggs was sentenced to 30 years but escaped over a London prison wall after serving just 15 months – and spent most of the rest of his life as a celebrity fugitive.

After undergoing extensive plastic surgery in Paris, Biggs made his way to Australia, living there with his wife and two children. Tracked down by police, he fled again in 1969, this time to Brazil.

Five years later, Biggs was traced once more, this time by a newspaper reporter. Metropolitan Police Detective Superintendent Jack Slipper, who had led police efforts to bring the train robbers to justice, flew out to Rio de Janeiro to arrest Biggs, allegedly greeting him in a beachside hotel, “Long time no see, Ronnie.”

Efforts to bring Biggs home were frustrated because by then, he had fathered a young Brazilian son – Michael Biggs – and authorities rejected British requests for his extradition.

Return by private jet

Biggs continued to live openly in Rio, trading on his notoriety by entertaining tourists, selling T-shirts and even recording the single “No One is Innocent” with the Sex Pistols in 1978.

In 1981, he was kidnapped by a gang of British ex-soldiers and smuggled to Barbados. But legal efforts to have him brought back to the UK once again stalled and he was allowed to return to Brazil.

By the late 1990s, Biggs was running out of cash and in poor health after a series of strokes. In 2001, he flew back to the United Kingdom on a private jet trip arranged by the Sun newspaper. He was promptly locked up in a high-security prison but then moved to a facility for elderly prisoners.

After that, Biggs and his family campaigned for his parole on compassionate grounds. This was finally granted in 2009, after he had been in ill health for some time.

He had been refused parole shortly before that because he “had shown no remorse for his crimes nor respect for the punishments given to him,” said Jack Straw, who was then justice secretary.

Michael Biggs said then that his father had expressed regret for the robbery, but did not regret “living the life he had.”

Britain’s Telegraph newspaper, in its obituary, makes the point that while Biggs won notoriety for the heist and his subsequent life on the run, “people tended to forget that he had seriously wounded the train-driver, Jack Mills, who died six years later having never recovered his health.”

Biggs’ death coincides with the release in the United Kingdom of a two-part BBC series about the 1963 train robbery that made him famous.

A Twitter account that publicizes Biggs’ books, @RonnieBiggsNews, said Wednesday: “Sadly we lost Ron during the night. As always, his timing was perfect to the end. Keep him and his family in your thoughts.”

CNN’s Damien Ward contributed to this report.