Story highlights

Haitian American Duwon Steven Clark returned to Ghana in search of his ancestors

He visited Cape Coast Castle, one of more than two dozen "slave castles" on the coast

Four out of 10 West African slaves shipped to the Americas never survived the journey

Clark's ancestors did. He says his presence at the castle shows the slavers did not win

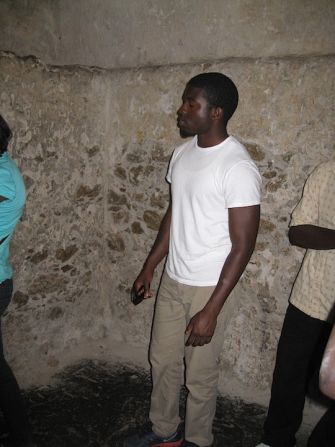

Duwon Steven Clark is standing on the white rock patio, just to the right of the now-silent cannons of Ghana’s Cape Coast Castle, trying to get himself around a memory he never had.

Clark, a 21-year old Haitian-American student at Florida A&M University, came to Cape Coast to find his great ancestors, men and maybe women whose names he doesn’t, and likely, won’t ever know.

What he found here was so much better, and so much worse.

“I just took a quick minute to look at the water crashing up against this castle,” he says. “It’s just overwhelming.”

Clark stares out at the sea, as if trying to figure the route the slave ships carrying his ancestors sailed from the shores of West Africa to Haiti, to the “New World.”

He is in Ghana studying abroad at the University of Ghana, trying, he tells me, “to get that African experience, that experience of being home and being connected and learning about where I came from and where my ancestors came from.” Below his feet and all around him, he is finding diabolical answers.

Tortuous voyage

Our guide tells us that between the late 17th and early 19th centuries, some three million West African slaves – many traded to the British by African tribes – were shipped out to the Americas from this ironically picturesque, fading white prison.

Four in 10 never survived the tortuous transoceanic voyage, crammed barely alive in the hull below the deck. Here one learns, just surviving to get on board was a victory of the human spirit.

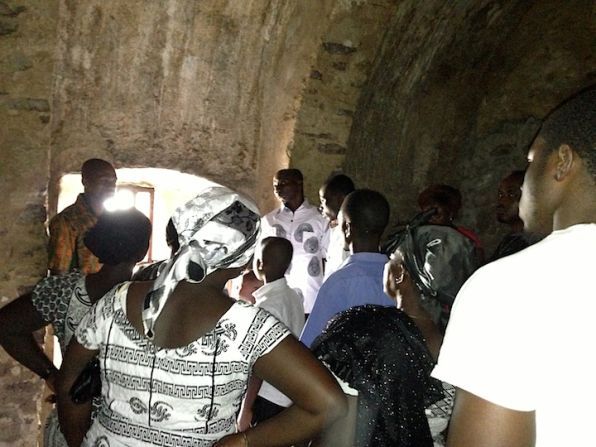

Our guide takes our small group from the sunny bright patio into the tunnel that leads to the men’s dungeons.

In one dungeon, Clark studies the thick stone walls and looks toward the two tiny windows high up near the ceiling at the end of the room.

He hears each word the guide says, grabs the words as they hang in the musty air: “They put about 1,000 men at a time in this room, no light. Many went blind. They had to go on the floor, and live in it.”

There’s only a small channel running through the center of the room, their sewer. “See this patch on the floor here?” our guide says. “This is what’s left of human excrement, 300 years-old.

“This is what they lived in, died in.”

The average stay was two to six months. Clark tells me, “1,000 men. How did they lie down to sleep? How could they bear the smell?”

The guide says: “Some slept sitting, others in rows, their heads between the legs of their fellows. After a while, they had no senses anymore. They were chattel.”

Clark sees a lot in the dungeon’s darkness. “I was just standing there in the dungeon room,” he says, “and I was thinking, how many songs were sung to get them through the night? How many tears fell? How many solemn prayers were enough?”

The ‘lucky ones’

Prayers indeed. The British built their church directly above the men’s dungeons. Our guide says the slaves likely could hear the Sunday prayers.

In the women’s dungeons, much smaller, the guide tells us, some 400 female slaves were kept.

“Can anyone tell me why they had women slaves?” he asks. Clark listens, the words hang, suspended across centuries.

The guide: “Breeding. Slave buyers in the Americas wanted to make sure their slaves could produce more slaves, so they sent some women too.”

A few women became the “lucky ones.” When the castle’s commander wanted companionship, the soldiers would march the women into the courtyard, and from a walkway above, the commander would pick one out.

She was washed and brought to him. If she got pregnant, she was sent to a house in town and taken care of, and her mulatto child was sent to school and treated well.

The words come slowly to Clark. “So the “lucky ones,” he pauses, taking a breath of repulsed recognition. “Those were the ones who were raped. They were the “lucky ones.”

Later, I realize this experience is so different for Clark than it is for most tourists, who are shocked by the barbarity but ultimately, one step removed. For them, it is history. But for Clark, it is personal. “I can’t feel disconnected,” he explains.

“These are the people you heard stories about, the people who came through your grandmother, your great grandfather, your great uncles – these are the people who I came through.”

Condemned cell

We cross the patio and walk into another room, small, tight, the walls made of thick stone, no windows.

The guide closes the door and all light disappears. A few people quickly become uncomfortable.

After a few seconds, he opens the door, and light pours back in. He explains this is the “Condemned Cell,” where they put slaves who resisted.

He says they threw them in here, behind three locked doors, and just left them, with no food, no water, no ventilation. On the floor and lower walls, you can see scratch marks.

Clark thinks of those slaves, their last scrawls of hope and life, vanishing in the darkness, as they brutally died. Clark says he feels helpless, angry. He wants to do something, anything, but time is the insurmountable obstacle.

“I wonder what I could have done to help that person make it through the night,” he says, “to help him through that moment when he felt it was so necessary to scrape the ground.”

And lastly, we walk toward the infamous door, the “Door of No Return.”

This is the doorway where slaves were led, to be loaded on to ships, their last moments in their native land.

As we walk toward the Door down the corridor, the guide points off to the right, to a deep tunnel where the slaves were walked.

He explains they never came to the surface, instead led through tunnels from the dungeons to the sea.

Clark steps through the Door and looks out. Our guide explains, in those days, the water came right up to the door. Now it has receded several dozen meters. But for Clark, the water, the reality, is still right at his feet.

‘So much anger’

I asked him what he would say to those who ran this place. He looks down, seems to shake slightly.

“Anger, just so much anger. But I would have so many questions why. No religion, no amount of wealth, nothing can amount or perpetuate or give you that confidence or okay to think that it’s okay to do this to another human being. I would just want to know why.”

I asked him what he would say to his ancestors, who survived this place and the journey by ship to live in the Americas as slaves, still strong enough there to make a family, to give him life centuries later.

“I would say, hold on. What you’re going through is not going to last long.”

Clark named American civil rights leaders Dr. Martin Luther King Junior and Malcolm X, Congolese independence leader Patrice Lumumba, and Ghana’s first president Kwame Nkrumah.

“It’s up to us to carry on the legacy of those who came after our ancestors.”

Unfinished story

For Clark, Cape Coast, and other slave forts like it up and down what they used to call the “Gold Coast,” is a story that is not finished.

It is making him something better.

“Being here today is going to enable me to step into those lanes I was afraid to step into before, and just walk proud, to not be afraid to go after those things that I hope for and to stand for those rights I dream of.”

He says he owes that to his ancestors who survived, and that it is a way of telling those who ran this place – they did not win.

Act of liberation

For Clark, what happened here centuries ago, is very much a part of the present.

Clark is angry, yes, but this visit is also an act of liberation.

In the early 2000s, the bones of two African slaves were repatriated from their U.S. graves to Cape Coast Castle.

They were carried back from the beach through the Door of No Return.

Our guide says, on that day, the horrific spell was finally broken. A sign over the door as one walks back through now says simply, “Door of Return.”

Clark walks back through it too. “Just make sure whatever you’re doing is for the right, for the just, and it’s always positive,” he says.

He tells me he leaves with a new purpose: To walk back through the Door, to carry his ancestors back through it, every day of his life.

The International Center for Journalists and the Media Foundation for West Africa sponsored David Gurien’s reporting trip to Ghana.