Story highlights

"Las Balsas" is the longest known raft journey in human history

The 1973 trip stretched more than 9,000 miles from Ecuador to Australia

It was the first known multi-raft crossing of the Pacific Ocean

The explorers were faced with violent storms and hammerhead sharks

Mike Fitzgibbons recalls 1973 with a mixture of fondness and tearful nostalgia.

That was the year he graduated from St. Joseph’s University in Philadelphia, celebrated his 24th birthday and married his first wife.

It was also the year he set sail on a trip that would enter the record books as the world’s longest known raft expedition.

Fitzgibbons was one of the “Las Balsas” explorers, a group of 12 hardy men led by the charismatic Spanish explorer, Vital Alsar, who set sail from Ecuador on three vessels fashioned from little more than tree logs.

Their aim? To reach Australia, some 9,000 miles away across the South Pacific. In the process, they hoped to prove that the Pacific Islands could have been populated by migrations from South America in the centuries before the Spanish Conquistadors arrived.

Alsar had made two attempts at the trip before. The first ended when his ship sank after its wooden frame became infested with teredo worms. The second – known as “La Balsa” – was successful, although many wrote it off as a fluke that could never be repeated.

The Las Balsas crew were out to prove the doubters wrong in what they hoped would be the first recorded multi-raft crossing of the Pacific.

“It was an adventure,” says Fitzgibbons, wistfully recalling how his participation in the voyage came to be. “Everyone thinks of these things from when they were a kid and here it was in front of me.”

He was introduced to Alsar via a mutual acquaintance in Mexico City a year before the trip. He recalled being impressed by the Spaniard’s knowledge on an array of subjects as well as his philosophical demeanor.

“He was like Santa Claus meets Jesus Christ,” Fitzgibbons says of the heavily-bearded Alsar, “like electricity to be around.”

Ten other suitable candidates were soon carefully recruited from across the world. Fitzgibbons was one of three Americans while the others hailed from Mexico, Chile, Ecuador, Spain and Canada.

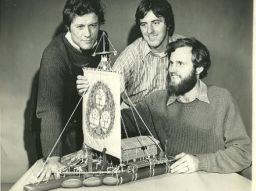

Each had to speak at least three languages, be capable of navigating at sea and make a scale model of the boats they would soon build together using instructions provided by Alsar.

While being an important lesson to familiarize the crew with the ships they would sail on, it was also a PR opportunity for the mission.

Alsar gave the models to an array of public figures and politicians to promote the voyage, including the surrealist artist Salvador Dali. In return, Dali donated an original painting which would be placed atop the sails of the vessels when weather permitted.

The balsa logs

The crew arrived in Ecuador early March and immediately set out for the jungle. Once there they sought out and cut down a number of balsa trees from which they would build the vessels.

Balsa wood was chosen because of its strength, durability and the fact it was used by tribes to construct rafts in the centuries before the Conquistadors came to South America.

After a week, the group gathered the wood they had collected and sailed down a nearby river to the port city of Guayaquil, where they would construct the vessels.

“We built them right there, shaped them, cut them,” says Fitzgibbons. “Three rafts with their cabins. They were very sturdy. They could take high winds, high waves. They were just like planks on the water. There was no rocking, we would just go up and down.”

As the sailors set out to sea, Fitzgibbons recalls there were few nerves. Each man had prepared well and was focused on the upcoming mission.

“We were convinced through Vital that, as hair-brained as everything may have seemed, it was well planned, thought out and safe,” he says.

“You knew you would have your challenges but everything you would do, you knew you did it for the day you would arrive in Australia.”

On board, the men divided tasks. Each would take two-hour shifts to sail in the morning and once again later in the day. Chores such as keeping the logs clean of seaweed and slime were also split, as was cooking.

The main pleasure of life at sea quickly became food. The group brought with them small rations of rice, beans and some preserves like marmalade and jams, while rainwater was captured in buckets. Their main nutritional source, though, came from the ocean – spending much of their time catching tuna, mahi-mahi and small pilot fish.

“Food became something you obsessed over. You daydreamed about things you couldn’t get. There was no milk, there was no cheese,” Fitzgibbons says. “There was not much talk about sex because you didn’t care, you were hungry. You didn’t think about it. Food became your big delight.”

Sharks begin to circle

Attracting tasty morsels to catch was never much of a problem. Barnacles soon started attaching themselves to the boats once at sea. This attracted small ocean creatures, which in turn lured larger marine life, which attracted fish.

Before long, sharks were following in the wake of this mini ecosystem, while curious whales were a frequent sight alongside the rafts.

“The sharks were pretty obvious. You’d see them coming around for the other fish,” Fitzgibbons explains. “We didn’t mess with them too much. Only twice did we kill the sharks that were keeping the food away.

“There was one time we had hammerhead sharks that one man didn’t realize were there. He threw a big tuna head out into the water on a line. This was picked up by the hammerhead. It literally started to turn the raft around until the line broke. That’s how strong it was. It was an ugly-looking thing. Huge, but ugly.”

Hungry sharks weren’t the only danger out on the open water. The weather was also a force to be reckoned with. On one occasion, when the ships were passing Tonga, a particularly violent storm struck, lasting for eight days.

“It was pretty severe. We had six days of just rain and then the last two days it was just huge waves that had built up over the time of the storm. You couldn’t even see the other vessels as they disappeared into the trough of the wave,” Fitzgibbons remembers.

“It was frightening just listening to the noise of the wind. It was so strong that the lines holding up the sail would vibrate like the string of a guitar because they were that taut.”

Amid the chaos, one of the three vessels became damaged and separated from the others.

“We didn’t realize until the morning that they were gone,” says Fitzgibbons. “It was worrisome as we didn’t have radio contact.

“We just kept sailing and kept to the routine as we had agreed to before. Everyone was silent at that point. Then, after seven or eight days, there they were on the horizon. It was great. Their radio had failed. They could hear us but we couldn’t hear them. It was remarkable.”

Such experiences, although terrifying at the time, have come to define the trip for Fitzgibbons. Alongside the moments of great laughter and comradeship, which he says were frequent, he learned most from them.

“When you’re trying to be reflective about these things, it would have felt like you weren’t on this expedition if you didn’t come through that,” he says.

“It made me see how people could function together and get through things. Sure, we were tired and wet and cold, but we got through it.”

The final stretch

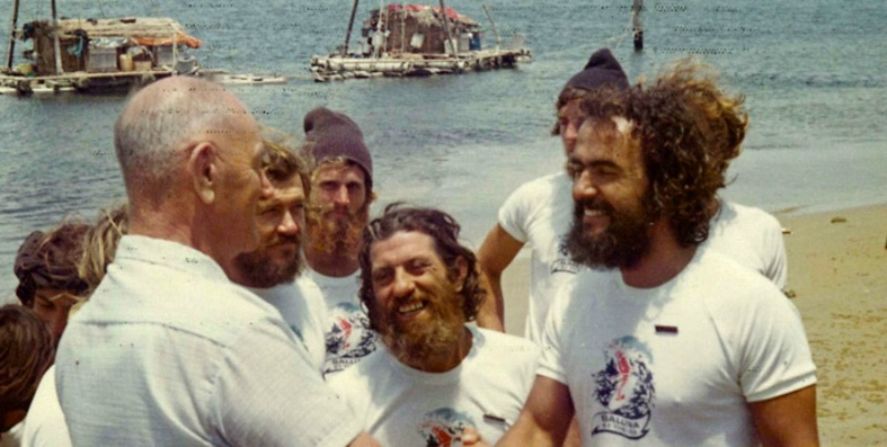

Eventually, after 179 days at sea and a distance of 9,000 miles, the Las Balsas crew had made it to Australia.

Bearded, bedraggled and exhausted, they landed on the shores of Ballina in New South Wales, where they were greeted by an excited local community.

The sailors had learned how to sing and play “Waltzing Matilda,” a folk song often referred to as the country’s unofficial national anthem, during their spare moments at sea and they performed the ditty for their delighted hosts.

Adapting to life on land once again, however, took some getting used to.

Some of the explorers have since spoken about how they didn’t get on with others in the group when they got back to land, but Fitzgibbons talks highly of everyone he sailed with.

He reserves the highest praise for Alsar, though, whose vision and strength of character made the journey possible.

It wasn’t until they were almost ashore he realized the pressure the captain was under, ensuring all of the men he had persuaded to take part in his crazy adventure had got there safe.

“I watched the worry just drain out of him. I thought, ‘My God, he did this,’ ” Fitzgibbons says, his voice breaking with tears. “It still makes me emotional just thinking of it.

“He made this happen and he got us there. I’ll never get over that. Everything else you can make in a movie. You can’t make that up.”

The 40th anniversary of the Las Balsas voyage came to pass last November, and a reunion celebration was held in Ballina with several of the sailors attending.

A small memorial displaying one of the rafts used during the journey remains in the town’s maritime museum to this day.

This exhibit aside, however, Las Balsas hasn’t stuck in the popular consciousness in the same way that other famous Pacific ocean raft adventures have.

The Kon-Tiki voyage undertaken by Norwegian explorer Thor Heyerdahl and five others in 1947, for example, has its own museum in Oslo. A 2011 feature film on the journey meanwhile was nominated for the award of best foreign language film at the Oscars.

Although a mightily impressive feat in itself, the Kon-tiki only sailed from Peru to the Polynesian island of Raroia, where it struck a reef. This meant it traveled roughly 5,000 miles less than the Las Balsas vessels.

For Fitzgibbons, however, recognition was not what the journey was all about. In fact, he kept his mementos of the journey hidden away for a long time.

“When Vital visited me once, he didn’t see anything in the house and he asked me, ‘Where are some of your souvenirs from the trip?’ I said I didn’t want to share the story. He said, ‘It’s your story, you should.’

“So now,” he pauses, before composing himself one final time. “Now, I do.”

See also: Heavy metal on the high seas

See also: ‘Beard saved me from jellyfish’