Story highlights

Scientists announce plans to sequence the entire genome of King Richard III

Monarch's remains were found buried beneath a parking lot in English city of Leicester in 2011

Tests may reveal Richard III's eye and hair color, and predisposition to certain diseases

Genome sequencing to be carried out before skeleton and samples are controversially reburied

Scientists are to sequence the entire genome of Richard III – the King found buried beneath an English car parking lot – in an attempt to discover once and for all what the long-missing monarch really looked like.

Experts hope the project will reveal the color of Richard’s hair and eyes, and uncover the genetic markers for any health conditions he suffered, or might have been at risk of, had he not been killed, aged just 32, at the Battle of Bosworth in 1485.

“It should give us an insight into his genetic make-up, his predisposition to disease,” said Turi King, the geneticist who will lead the genome project.

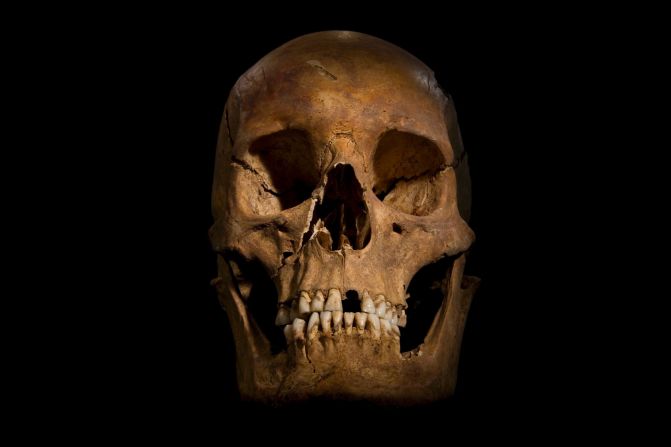

King, who carried out the DNA tests on the bones, proving their royal identity, said she was particularly keen “to see whether or not Richard was predisposed towards scoliosis, for example.”

If the tests succeed, they should enable historians to tell just how accurate portraits of the controversial King are, and give them an insight into whether pro-Tudor propaganda in the decades after his death meant he was painted in a deliberately unflattering light.

“There are no contemporary portraits of Richard,” said King. “All the portraits that exist post-date his death by about 40 to 50 years onwards. So it’s going to be interesting to see what the genetic information provides in relation to what we know from the portraits.”

Richard III is best known as the hunchbacked anti-hero of Shakespeare’s play, whose physical deformities echo his villainous nature, and who is blamed for the murder of his nephews, the princes in the tower, but many modern historians believe that image is exaggerated, and have sought to rehabilitate his reputation.

He will be the first known historical figure to have his genes studied in this way; scientists have previously sequenced the genomes of Oetzi the Iceman, a number of Neanderthals, and most recently a hunter-gatherer from Spain.

Sequencing the first human genome took 13 years and cost about $3 billion; now it can be done for a fraction of that cost, in a matter of hours.

Read more: Body found under parking lot is King Richard III

Richard’s remains were found under a parking lot in Leicester in 2011, by archaeologists from the city’s university looking for the lost Grey Friars church.

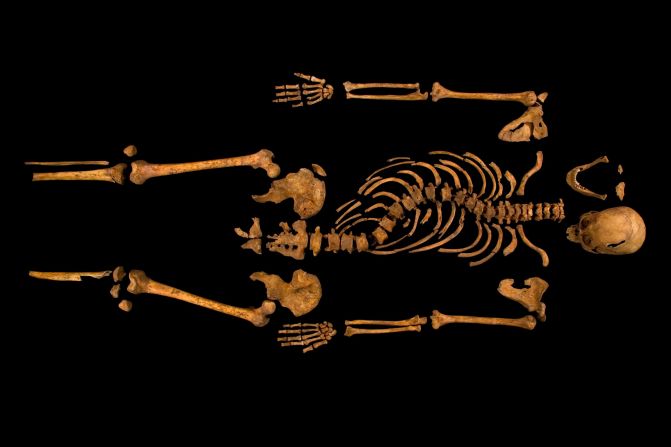

Their announcement in February 2012 that the almost-complete skeleton they had uncovered – featuring a strikingly curved spine and deadly battle wounds – was that of a king missing for more than 500 years ignited worldwide interest.

But it also sparked controversy: An argument over where the bones will be reburied – in Leicester, close to where they were found, or in York, which some supporters believe would have been Richard’s choice – has developed into a lengthy and bitter legal battle, with no end in sight.

Wherever is eventually chosen as Richard’s final resting place, the genome project will ensure the king leaves behind a lasting scientific legacy.

“Once he is reinterred, everything is reinterred,” said King. “The bones, the samples, everything. We can’t keep anything, and that’s the reason for doing this now, while we can. We have the technology, so this opportunity has come along at the right time.”

Once completed, the full details of Richard’s genome will be published online, offering historians and scientists intriguing research opportunities.

“As we know more and more about which genes are responsible for what, we can keep going back to check for evidence,” King said, adding that experts should be able to look for clues to everything from curly hair and obesity to lactose intolerance and heart disease.

King said there was even the possibility, in future, of discovering clues to Richard’s temperament.

Read more: Richard III - the mystery of the king and the car park

Members of the public will also be able to access the genome, and even compare it to their own genome to see if they share a genetic link with the last Plantagenet king.

“We’re all related to Richard III, it’s simply a matter of degree,” said King, “But some people would love DNA evidence of that link, and this will mean they can check for matches,” though she cautioned that a genetic link is not the be-all and end-all of proving a royal family tie.

“Accurate documented genealogy is more proof of relatedness than DNA, but people see DNA as a kind of magic bullet to prove everything,” she said.

One man who has both is Michael Ibsen, Richard III’s closest living relative. King will also be sequencing Ibsen’s genome, to look for any other genetic similarities between the pair – aside from the matching mitochondrial DNA which allowed her to positively identify the Leicester remains as those of the long-dead English ruler.

“Theoretically, Michael Ibsen and Richard should not be genetically related any other way – apart from the mitochondrial DNA – after so much time, but it will be really interesting to see if there are other similarities,” King said.

The project, which is expected to cost about $165,000 (£100,000), is being jointly funded by the Wellcome Trust, the Leverhulme Trust and Alec Jeffreys, the scientist who developed genetic fingerprinting, and who, like King, is a professor of genetics at the University of Leicester. It will be carried out in Leicester and at the University of Potsdam in Germany.

So could the controversial King ever be cloned? The experts insist that would be impossible – for a host of reasons – “you can’t clone anything from fragmentary DNA,” says King.

“Practically, you can’t – and morally, you can’t,” insists Dr. Dan O’Connor, head of medical humanities at the Wellcome Trust. “It’s a whole different ethical issue.”

READ: Richard III’s last battle - new War of Roses’ over remains

READ: King Richard III had worms, scientists say

READ: Body found under parking lot is King Richard III

READ: Richard III - the mystery of the king and the car park