Story highlights

As many as 150.000 people living in Zaatari refugee camp

Star for the Jordanian women's national team Abeer Rantisi is coaching in the camp

Rantisi says coaching helps to build refugeesl' confidence

Camp costs $1.6 billion a year to run

Amongst the clouds of dust kicked up from the desert by the hundreds of new arrivals who pitch up every day at the Zaatari refugee camp – just 15 kilometers from the Jordan/Syria border – Abeer Rantisi is planning her next lesson.

The twenty-six-year old is short, hair tied back, her thick-rimmed glasses sitting wonkyly at the end of her nose. She is standing outside a large marquee where a group of Syrian men is being taught the basics of soccer coaching.

“‘Football,” she tells CNN, her eyes moving to a group of young children nearby, screeching with laughter as they kick a football around on a sand pitch, “We all speak football.”

Rantisi is a star for the Jordanian women’s national team, who are preparing for a tournament that could see the kingdom qualify for the World Cup finals for the first time in their history.

But, for now, she has more important work to do. She coaches soccer for Syrian girls and young women who have fled the horrors of civil war and found themselves in what has become one of the biggest refugee camps in the world.

The sound of a child’s laughter is rare in Zaatari.

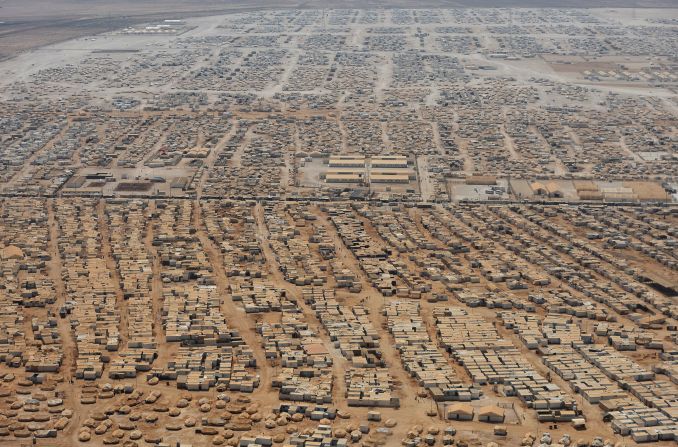

Since the start of the Syrian civil war– the conflict marked its third anniversary in March – this tiny hamlet has been transformed into one of the biggest cities in the country.

As many as 150,000 people live here now. Hundreds come every day, sometimes more, sometimes less, depending on the brutality of the fighting just a few kilometers away.

They have built a life of semi-permanence.

According to the United Nations there are now close to 700 shops in the camp and nearly 60 mosques.

You can buy cable TV from one of the many tents set up to supply the growing population. There’s a wedding cake shop, a place to buy wedding dresses and even a pet shop.

It costs $1.6 billion a year to run Zaatari, but the human cost is immeasurable.

Almost every player Rantisi coaches says they have been confronted with the unimaginable: bombings, the death of entire families, assault, rape.

“The main thing we can work on is self-confidence,” Rantisi explains of the fragile emotional and physical state her players arrive in.

“To bring those people here and tell them they can achieve whatever they want. We have to make them resilient because they were suffering in Syria.”

Dealing with the emotional scars of a civil war is a tough job, but there is also the added obstacle of social conservatism to overcome.

Almost everyone at Zaatari has come from Syria’s southern, rural, conservative Sunni population.

Young girls have simply never played football in that environment. The biggest issue in such a sprawling, impersonal camp, according to Rantisi, is privacy.

“They have all come from conservative communities and are not allowed to play in public so we have to make sure that they are hiding all the time,” she says.

“It’s a really big problem here. Because you can see the camp it’s open from all angles so we have to find a safe place for them to play. We have to find private places just for the girls to come.”

In private, away from the gaze of men, Rantisi works with her players, but it takes time for her to earn their trust.

“The women in Zaatari have no idea about sport at all,” she explains. “In the first lecture we say: ‘We are national team players. We have come here to talk about sport.’ They ask: ‘What do you mean? What is sport?’”

It is not an uncommon question in the region. While women’s soccer has boomed around the world, the game in the Middle East has been fraught with religious and cultural opposition over the past decade.

In Kuwait a nascent women’s national team was effectively banned in 2007 after lawmakers decided it was ‘un-Islamic’ for women to play soccer.

The Palestinian women’s national team had to fight social conservatism within its own communities to build a mixed team of Muslim and Christian players.

Saudi Arabia still has no women’s team.

But attitudes are changing.

The Jordan team has only existed since 2005 and has been backed with money and support from Prince Ali bin al Hussein, the young half-brother of the king, who was recently elected as a vice-president on FIFA’s powerful executive committee.

Fifteen new training centers for young girls have been built and Prince Ali has been instrumental in pushing through a rule change that allows Muslim women to wear a modified hijab to cover their hair during FIFA matches.

Originally they had been prevented from doing so on the grounds that the hijab was a religious symbol. But the change could revolutionize the game in the Middle East and open soccer to millions of women who would otherwise be prevented from playing.

In the past few years alone national women’s teams have been set up in the UAE, Qatar and now, finally, Kuwait too.

The greatest success story, though, has been the Jordanian national team with Rantisi, who cites French World Cup winner Zinedine Zidane as her inspiration, in the heart of midfield

“I’m from Amman and started playing when when I was 13,” she recalls. “In Jordan we don’t have the same problems anymore as say with the Palestinians.

“We don’t have the same social problems as they have. But we used to, when we started in the past.”

In just eight years the Jordan team has gone from nothing to qualifying for the Asian Cup.

Rantisi scored a hat trick in a world record 21-0 victory over Kuwait in one qualification match.

That tournament takes place in May and if Jordan reach the semi-finals they will qualify for the World Cup, the first time a team from the region will have ever made it.

“I play as a central midfielder so it was fun to score,” she says, a little embarrassed at the huge scoreline.

“We have to look at new teams like Qatar and Kuwait and support them. But,” she adds, laughing now, “we needed the 20 goals as Uzbekistan were in the same group and they scored eighteen!”

For Prince Ali, the success of the team on the pitch vindicates an investment in the women’s game that few others in the region were willing to make.

“Our girls have qualified for the Asian Cup, the first team ever from West Asia and that’s down to them and the investment we’ve put in,” he explains of Jordan’s recent success on the pitch.

“We chose a coach from Japan, bearing in mind they are World Cup champions, and we hope they can make it to the World Cup.”

The Zaatari project is a collaboration between the Asian Football Development Project, set up by Prince Ali, and UEFA, European football’s governing body.

The aim is to use football to promote healthier living and also to fill the idle hours that refugee camps provide in abundance. More than 1,000 children and young adults under 20 are in the program, with 80 more being trained to coach.

“All the children that arrive are completely devastated,” explains Bassam Omar al Taleb, a 31-year old Syrian who had himself fled his home in Daraa a few months before. Once a keen amateur soccer player, he is now coaching Zaatari’s new arrivals.

“They have seen their family members killed before their eyes and the journey to Jordan is a difficult one,” he says. “Through football we at least try to remove the sense of fear and regain some sense of normalcy.”

Meanwhile as the war in Syria continues. Zaatari’s numbers swell every day.

“It is a really difficult job,” Rantisi says.

As the coaching class for young Syrian men finishes, the children are still on the sand pitch, shrieking as they chase the ball as a pack. “But,” Rantisi adds, “we have to bring them back to life.”