Follow us at @WorldSportCNN and like us on Facebook

Story highlights

Steve Williams, former caddy of Tiger Woods, reveals secrets of being a great golfing bag man

Williams has helped win 150 tournaments, but retirement looms this year

Ian Poulter's bag man Terry Mundy only became a caddy after a conversation in a pub

Mundy says caddies can still sometimes be treated like second-class citizens at events

They carry a bag for a living but these men can bring home six-figure incomes. They often spend more time with their bosses than their wives, and their working “marriages” can end in a messy divorce.

Welcome to the world of a caddy – the golf world’s unsung heroes.

At the top of the pile is Steve Williams, arguably the one superstar caddy in global golf, a bag man who has earned well in excess of most professionals thanks predominantly to his past partnership with Tiger Woods.

His wealth is estimated at $20 million and he was once New Zealand’s highest-paid sportsman.

It has been enough to pursue his other, admittedly expensive, sporting passion of saloon-car racing with his own team, appropriately titled Caddyshack. He also founded his own racing series, which he funds, and does about 25 events a year.

But how has he merited such big bucks? Well, 36 years into his career he has overseen 150 tournament wins – more than any other caddy in golf history.

Now working for defending Masters champion Adam Scott, Williams argues that key to his job is the ability to understand people.

“You can teach someone to do the yardage and read the course but being a good caddy, it’s not easy to explain,” says the 50-year-old, who previously worked for major champions Greg Norman and Ray Floyd.

“It’s almost like you have to stand in a player’s shoes, see what they’re seeing and feel what they’re feeling, to be them.”

Before Williams, caddies were very much behind the scenes – but no longer.

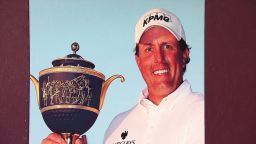

When with Woods, he described his arch rival Phil Mickelson as a “pr***” and he was castigated for a racist barb against his former employer some time after the 14-time major champion had fired him. And then there was his over-the-top celebration and interview when Scott won the pair’s first tournament together.

Other caddies have been the subject of controversy too.

En route to Matt Every’s victory at the Arnold Palmer Invitational last weekend – where Scott and Williams blew a winning position on the final day – the American’s caddy Derek Mason was caught on camera shouting “f***ing lay-up” after a particular shot.

Williams clams up when asked about his relationship with Woods but he will always be known for his time with the world No. 1 – hardly surprising given the American won 13 of his 14 major wins with the Kiwi in tow.

Read: Woods - Don’t rule me out of the Masters yet

“You almost have to teach yourself the psychology side of things,” explains Williams, who is extremely affable in conversation. “I think I’m a good reader of people – you have to be able to observe people over a long period of time.

“You need to see how they cope under pressure and you have to see them at both their best and worst to see how they tick.”

In caddying terms, Williams is something of an anomaly.

Most admit to stumbling into the job, but for Williams it was different.

While friends at his stunning local course – Paraparaumu Beach Golf Club – dreamed of being the next Peter Thompson, the five-time British Open winner from Australia, the teenage Williams merely wanted to caddy for him … and got his chance, the first time he ever carried the bag.

Now, with potential retirement looming, Williams plans to either give up altogether at the end of this season or else do the job part-time so he can spend more time with his eight-year-old son in New Zealand.

“You have to keep your enthusiasm and find ways to keep refreshed. You can get that by changing jobs or in one job by changing your goals,” he says.

“I’ve been lucky that I’ve caddied for players that haven’t played loads of tournaments in each year.

“And it’s been interesting working with different players. I think it takes six to 12 months to adapt properly to a player, to learn their idiosyncrasies.

“It just doesn’t happen overnight but, if you do it properly, that’s when you can help best when the chips are down. And the other trick is that you’re always trying to improve.”

Terry Mundy may not have enjoyed the riches of Williams as a caddy but, having worked for former women’s world No.1 Laura Davies and with his current partnership with 2012 European Ryder Cup hero Ian Poulter, he has enjoyed the job’s trappings.

He has also experienced the lot of many caddies scraping around to make ends meet on the global circuit.

“I remember it used to be four of us to a room sometimes sharing two towels or whatever,” he says.

“It’s tough. You go to those flyaway tournaments and you’re easily spending $1,000 on a flight and then there’s the hotel. If your player misses the cut, you’re out of pocket for that week. That can be tough but I’m lucky with Ian.”

The Briton’s foray into the role was somewhat fortuitous. Drinking in his local pub by Woburn golf course one day, he was asked to stand in for a sick caddy. The round went well and he was invited back.

Not long afterwards he was offered voluntary redundancy in his printing industry job and he took the plunge to become a caddy full-time.

“It’s a lot better but it’s still not quite where it should be,” says Mundy.

“At many of the American courses you get treated fantastically well but at others it’s a case of ‘what are you doing here?’ and you’re made to feel like you’re getting in the way.

“It’s odd as you’ll get some caddies turning up in $80,000 to $100,000 cars and yet they’re treated like idiots.”

As for the trick to be a good caddy, Mundy argues he has to play many different roles.

“A caddy’s a little bit of everything: you can be a coach, a psychologist, you’re there to keep the good rounds going and to turn the bad ones around, you’re there to offer advice, be a friend, a bit of everything. But at the end of the day I can’t make him play.”

One key piece of caddy advice is not to fall out with your boss, which is understandable given Mundy says “we spend more time together than we do with our wives probably.”

Chris Harmston is slightly lower down the caddying rung than Williams and Mundy in the relative infancy of his bag career, which began when his once promising playing days were curtailed by back and wrist injuries.

He caddies for Englishman Ross Fisher, for whom he was the best man at his wedding.

It is a fledgling partnership in its second full season that is clearly working, the pair having celebrated victory at the European Tour’s Tshwane Open in South Africa this month.

“After Ross’ win the other day, I heard him say that ‘no one knows my game better than Chris,’ and he’s probably right as we’ve played for so long together,” says Harmston. “As friends, it makes it even more special to win together.

“With Ross, I like to take a step back and think what’s the worst can happen in a situation and, if I have something to say, Ross will listen.

“He knows at the end of the day I’m there to help and he’s in charge so, if he doesn’t like the decision, he won’t listen to it.

“But there’s the balance of knowing when to shut up and also knowing when to take a player’s mind off things – just to talk about anything, really, as you’re going around. There’s an element of being an amateur psychologist to it.”

Caddies are, in essence, the ultimate multitaskers – but with a shelf life, very much at the whim of the players they work for.

“Often if a player is in a slump, they think the answer is to switch caddies,” says Mundy. “That’s not usually the answer.

“You look at a lot of the top guys, like Phil Mickelson with his caddy Bones. Those players are pretty honest guys and they stick with their caddies, and usually see the benefits.

“The best players tend to have the longer caddy relationships.”

It’s those guys that are worth their weight in gold.