Editor’s Note: Sam Gaskin is a New Zealand-born writer who has lived in Shanghai since 2007. He reports mainly on arts and culture in China.

Story highlights

China counts 4,000 museums at the end of 2013, meeting its five-year goal two years early

New museums promote culture but are also used for corporate branding and for anchoring China's new cities

What will become of these architectural wonders if the museums fail to attract visitors?

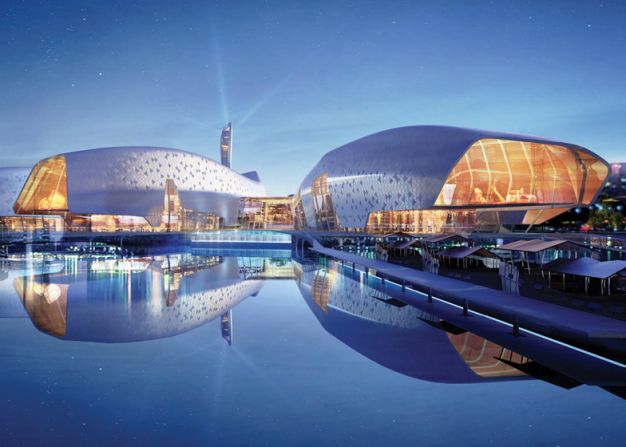

With its expansive steel skin, tall parasol-shaped concrete pillars, and huge vestigial coal hoppers, the 33,000-square-meter Long Museum West Bund makes a grand impression in a former industrial site beside Shanghai’s Huangpu River.

Launched at the end of March, the museum is the second and the largest private institution established by prominent Chinese art collectors Wang Wei and her husband Liu Yiqian. It has the potential to become Shanghai’s equivalent of a Guggenheim or a Whitney.

Yet as significant as it may someday be, the Long Museum is a mere spark in the explosion of China’s ongoing museum boom.

In 2010, the National People’s Congress outlined a five-year plan that, among other things, aimed to see China’s high-speed railway network reach 45,000 km and its number of museums increase to 3,500 nationwide.

The idea that culture can be laid like train tracks may be moot, but there’s no question that this cultural infrastructure is being rapidly developed. By the end of 2013, two years before deadline, China already exceeded its goal, tallying a total of 4,000 museums.

“Museumification”

Museum experts observe that China’s strategy is focused on building new museums, while the problem of setting up quality exhibition programs and finding an audience is dealt with later.

For the first phase of that strategy, the country is still in its early stages.

“China plans to elevate the per-capita number of museums to equal international levels. The short-term goal is to have one museum per 250,000 people,” says Jeffrey Johnson, director of Columbia University’s China Megacities Lab.

Johnson calls this aggressive proliferation of institutions the “museumification” of China. It is an aggressive plan to fast-forward the development of the cultural sphere. The UK counted 3.12 museums per 100,000 people in 2011, but this number took more than a century to achieve.

One reason China is exceeding its museum building goals is that, in addition to state-run institutions, many new museums are being built to service corporate and private interests. Property giants Times Property, Rockbund, and OCT have all built art museums to garner interest in their real estate developments.

Shanghai’s Tobacco Museum provides propaganda in favor of smoking, while the Museum of Glass, widely celebrated for its design, was built so the owners could develop the land while satisfying a legal requirement that they continue to use the land in an industry-related way.

Nationwide craze

China’s new museums aren’t all concentrated on the country’s prosperous east coast.

“The good quality museums are pretty well spread out, even in remote places,” says Clare Jacobson, author of New Museums in China. “If you have an archaeological site in nowhere northern China you’re going to build a museum on top of it to protect that site.”

“Ordos (Inner Mongolia), where they’re trying to set up a new town, actually has two museums that are used as focal points in the urban planning of that city, much like a church or town hall would be used in the West.”

From an architectural perspective, Jacobson is enthusiastic about the quality of many of China’s new museums. She cites the Museum of Handcraft Paper – “a beautiful little project right on the Burmese border” – as particularly impressive, as well as the Norman Foster-designed Datong Art Museum in Shanxi Province.

“Datong is not completely third-tier or anything but it’s not Beijing or Shanghai, so for Foster to be building a huge museum there, for me, is something,” says Jacobsen.

Money matters

Monumental government institutions, such as the China Art Palace, occupy some of the country’s most impressive buildings, but successful museums provide more than just awesome architecture.

Jacobson cites private art museums such as the Rockbund in Shanghai and the Times Museum in Guangzhou as institutions that have not only interesting architecture but also quality exhibitions and strong events programs.

Viewed holistically, Jacobson says, “a lot of the successes are private museums rather than the state-run museums.”

Li Xu, the Deputy Director of the state-run Power Station of Art (PSA) museum, says: “The government is still in the process of developing a system for supporting established museums.”

Li helps to run the 41,000-square-meter mega museum, often likened to another converted power station, the Tate Modern in London. It has no collection of its own, an annual budget of just RMB 20 million, and fewer than 10 staff to arrange exhibitions.

“Compared to public museum budgets in developed Western countries, our exhibition budget is very low,” Li says.

The Tate’s total income for 2012-2013 was nearly £158 million. That kind of big budget is able to draw in big crowds, such as the 4.8 million visitors in 2013. In Shanghai, the PSA received 380,000 visitors in that same year, a modest number for a city as large as Shanghai.

While the PSA is a young institution, having only opened in 2012. The activity of museum going itself remains relatively new in China, and these factors only emphasize the need for bigger budgets, better exhibition design and more effective outreach programs to build and educate a new audience.

“I think necessarily in the development of China the ‘hardware’ comes before the ‘software,’” says Jacobson. “It just does. There are models of that in industry and in housing.”

She believes that museums here are often vanity projects, generating spectacular architecture but vast quantities of underutilized space.

For the moment, she thinks China lacks enough experienced curators, researchers and museum directors, but that this is changing.

“There continue to be more university-level programs established in China offering museum and curatorial studies, and more and more Chinese students (are traveling) abroad for education in internationally established programs,” says Jacobson.

Architectural legacy

The danger of building a vast infrastructure network of any kind in anticipation of demand is that the demand doesn’t always arrive. There’s been notable unevenness in many areas of China’s growth, with forests of apartment blocks and entire speculative cities lying empty. With many new museums devoid of visitors, the same could happen in the cultural sphere.

The China Megacities Lab research project is watching to see how museums in China might evolve. “Are there new roles—socially, culturally, politically—that the museum is playing? What new architectural forms and spatial organizations are being invented to accommodate these new ambitions?” Johnson asks.

And if museums in China do evolve into wholly different forms, what will happen to the buildings being built? Clare Jacobson says the new architecture is worthwhile, regardless of the ‘museum’ label.

“Actually you do need a few places of beauty within this vast array of residential towers and boring office buildings. And I think the quality of a lot of these museums is just stunning, from both international architects and local architects. I think those buildings will remain – whether they’re used as museums or not is a different question. The buildings themselves will be important for a long time.”