Story highlights

World sees Ukraine in turmoil, but reality is different, writes CNN's Tim Lister

Lister: Only one town in eastern Ukraine -- Slovyansk, is truly held by pro-Russian protesters

But most people go about their lives almost oblivious to the upheaval, he writes

There seem to be more weapons in circulation, compared to two weeks ago, he says

The world sees Ukraine in turmoil, a country divided between Russian speakers and Ukrainian nationalists, its towns and cities roiled by occupations, its highways dotted with improvised barricades.

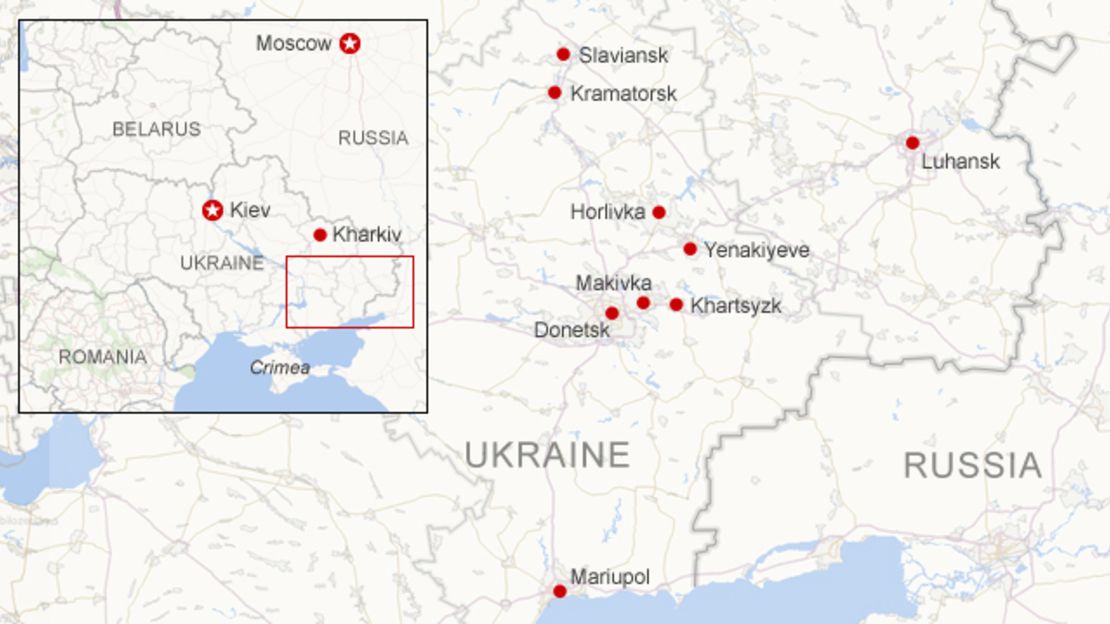

The reality is rather different. Only one town in eastern Ukraine – Slovyansk, is truly held by pro-Russian protesters, with roadblocks at several entrances. Its defenders are a mixture of the “men in green,” dozens of well-armed fighters wearing fatigues and balaclavas, teenagers looking for some action and what might be termed the Baboushka Brigade, middle-aged women with flashing gold teeth who decry the Kiev “junta” and see Vladimir Putin as their savior (and the prospect of Russian ownership as bringing improved pensions).

A relatively compact town of narrow streets, with several river crossings at its outskirts, Slovyansk is easy to defend. The active pro-Russian groups there – civilian and in uniform(s) – seem to number no more than several hundred. Of the 130,000 inhabitants, many seem sympathetic to the pro-Russian protesters – or more accurately hostile to the government in Kiev, which they see as dominated by nationalists who will sell out to the European Union and NATO. But most people go about their lives almost oblivious to the upheaval. Weddings take place, people sit by the lake eating kebabs and pizza, the outdoor market bustles.

It doesn’t feel like Sarajevo, and the warning by the self-declared mayor, Vyacheslav Ponomaryev, that it could be the next Stalingrad, one of the defining battles of World War II, seems surreal. Ponomaryev says Slovyansk is under siege by the Ukrainian army, but Ukrainian troops have done little more than approach roadblocks on the outskirts – only to withdraw. Trucks negotiate the slalom of checkpoints on their way to and from the Russian border. Commerce can’t stop for the rebellion. And a few miles away, sightseers take in Svyatohirsk’s historic monastery, with its gleaming blue and gold steeples.

In Donetsk, the region’s capital and Ukraine’s fifth-largest city, up-market fashion stores are busy; the leaders of the Ukrainian football league, Shakhtar Donetsk, play home games as scheduled; cafes are full in the spring sunshine; the airport is open and functioning normally. You would only know something was abnormal by approaching the regional government building, an 11-story slab of concrete surrounded by tires and festooned with Russian and Donbass flags and less than complimentary banners about NATO and U.S. President Barack Obama.

Inside there may be a couple of hundred pro-Russian protesters at any one time, including the leadership of the Donbass People’s Republic. Outside are a similar number — supporters, onlookers, miners in orange helmets who fear that if Ukraine joins the European Union they’ll be out of a job because of more stringent health and safety regulations.

The rest of the city works, worships and worries about the political paralysis that has engulfed Ukraine. Of a city of just under 1 million, a few hundred are involved in political agitation.

In Mariupol, Kramatorsk, Horlivka and other towns across the Donetsk region where government buildings and police stations have been taken over, there is little sense of momentum in the pro-Russian protests. In Horlivka, a gritty industrial town north of Donetsk, a platoon of the Babushka Brigade stood beneath Lenin’s statue outside the sleepy City Hall last week, ready to tell anyone who would listen that all they wanted was a referendum on their future, the chance to be free from the “fascists” in Kiev.

But there do seem to be more weapons in circulation, compared to two weeks ago. At a roadblock north of Slovyansk, on the main road to Kharkiv, a CNN team was briefly inspected last week by a couple of teenagers waving hand guns apparently liberated from a police armory.

And there are other ominous signs. Until now, the rarity of pro-Ukrainian rallies in the east has prevented street clashes. But a pro-Ukrainian event attended by several hundred people on Monday was attacked by pro-Russians wielding bats and clubs — was the first political violence of any consequence in the city for more than three weeks. On the same day, the mayor of Kharkiv was shot and wounded, and pro-Russian “men in green” seized another town hall at Kostyantynivka, near Slovyansk.

Still, words like uprising or insurgency, let alone civil war, the phrase sometimes deployed by Russia, don’t really describe events in eastern Ukraine.

Much depends on whether pro-Ukrainian groups in the east are prepared to mobilize in the next month, during which the “referendum” being organized by pro-Russian protesters will take place to decide whether Donetsk and Luhansk should leave Ukraine (May 11), followed by Ukraine’s presidential election two weeks later. If they do, then the potential for unrest grows.

The numbers involved so far — on either side — suggest neither widespread bloodshed nor a decisive resolution of the crisis are imminent. The Ukrainian government — short of special forces and equipment — seems incapable of reasserting its authority in towns where pro-Russian protesters have hoisted their flags.

The debate rages about how far the Russian government is exploiting, stoking or wildly exaggerating anti-Kiev resentment. To many observers, President Vladimir Putin seems intent on keeping the Ukrainian government off balance rather than invading. Cliff Kupchan, of political risk consultancy Eurasia Group, says “his visceral desire to influence Ukraine’s trajectory will remain, and he will pursue his goals of securing Ukraine’s geopolitical neutrality and political federalization with unabated vigor.”

His long-term goal, says Kupchan, is “grabbing territory through proxies and generally destabilizing Eastern Ukraine, thereby achieving de facto ‘federalization’ through Russian influence over the east.”

Eastern Ukraine is as much, perhaps more, a battleground between East and West as a battle on the ground. The rhetoric flies in both directions. The Russian foreign ministry accuses the Ukrainian government of building detention centers resembling fascist concentration camps for “disloyal citizens.” British Foreign Secretary William Hague says Moscow is “undermining its own influence in its neighbourhood, steadily disconnecting Russia from the international community and damaging Russia’s own prosperity and security over the long-term.”

In the game of geopolitical poker, the U.S. and Europe have added modestly to the list of Russian individuals and companies sanctioned, hoping the markets will do the rest by further punishing the Russian stock market and the rouble. Russia’s Deputy Foreign Minister, Sergei Ryabkov, responds by calling the measures meaningless, shameful and disgusting.

Who holds the winning card? The Russian writer, Vladimir Sorokin, a veteran observer of politics in his country and rare voice of dissent, admits to being at a loss, because Putin’s intentions are impossible to read.

Writing in the New York Review of Books, Sorokin says: “Unpredictability has always been Russia’s calling card, but since the Ukrainian events, it has grown to unprecedented levels: no one knows what will happen to our country in a month, in a week, or the day after tomorrow.”

Ukrainians could say the same.

READ: Ukraine crisis: EU names 15 individuals targeted by latest sanctions

READ: Russia vows ‘painful’ response to new U.S. sanctions over Ukraine