Winning Post is CNN’s monthly horse racing show. Click here for times, videos and features.

Story highlights

The Craven Breeze Up Sale is Europe's premier sale of its kind

Past horses to be purchased here include Rosdhu Queen and Great White Eagle

The breeding industry is slowly emerging from the effects of the global economic downturn

Although potentially extremely lucrative, buying and selling horses is a risky venture

On an April morning at Newmarket’s famous Rowley Mile, a stretch of turf so hallowed it traces its origins back to Britain’s King Charles II, the fate of Lot 99 is about to be decided.

The two-year-old chestnut filly will have just three furlongs, or 600 meters, to persuade potential buyers that she has what it takes to progress to the next stage of her career as a racehorse.

She gallops past the grandstand, hooves thundering and nostrils flaring, hitting a top speed of around 60 kilometers per hour (37 mph).

As she passes the makeshift winning post, her jockey eases her down to a jog. From here she will return to the warren of stables clustered around Terrace House, the headquarters of Tattersalls auctioneers, where she will await her destiny.

The Craven Breeze Up Sale is Europe’s premier auction of its kind. The top owners, trainers and agents from around the globe are gathered here with one goal in mind: to snap up a future champion.

Past gems to have been purchased in previous years include Cheveley Park Stakes winner Rosdhu Queen and next month’s Epsom Derby hope Great White Eagle.

Tattersalls holds nine sales a year, selling racehorses at every stage in their career from yearlings to breeding stock, via two-year-olds and racehorses in training. That’s nine occasions for potential owners, breeders and trainers to paw over every detail of a horse’s pedigree, conformation (or body structure) and temperament in order to assess whether he or she has what it takes to become the next Frankel.

The Craven Sale is dedicated to unraced two-year-olds. Unlike the yearling sales, when buyers must take a gamble on unbroken horses often straight out of the paddock, it allows potential suitors to see the horses gallop. In theory, this removes an element of the risk inherent in the selection process.

“When you’re buying a foal or yearling you’re a long way from the finished article,” explains Tattersalls marketing director Jimmy George.

“You have the pedigree and the physical conformation of the horse, the way it moves at the walk, but that’s it. With two-year-olds, you’re getting that little bit closer. It’s a few more pieces of the jigsaw which makes up the quest for the perfect thoroughbred.”

Harry Herbert, racing adviser to Sheikh Joaan Al Thani’s Al Shaqab operation, agrees that the sale gives buyers a better idea of how the horses have developed physically.

“At a yearling sale you can only see them at a walk. Here, you can time them over a couple of furlongs and get some idea as to movement,” Herbert says.

With more than 100 horses in training split between the UK and France, Al Shaqab has ambitions to become one of the dominant forces on the global racing scene, so the stakes are high.

Herbert is expecting to walk away with “a handful” of two-year-olds here to add to the Sheikh’s roster.

Back at the stables, Lot 99’s consignor Norman Williamson reveals he is pleased with his filly’s work. “That was the plan, to bring her here, and she’s got it all done now. Hopefully people will like her,” Williamson says.

There is certainly a lot to admire. Her sire is the illustrious Galileo, preeminent stallion of his generation and sire of Frankel, regarded by many as the greatest racehorse ever produced. Her dam is Flamingo Sea, a useful racehorse in her own right who has gone on to produce six winners so far as a brood mare.

“You don’t see many Galileos breezing,” enthuses Williamson. “She’s a very good-looking filly, great temperament. We’ll just have to see.”

In 48 hours she, along with 127 other horses, will be auctioned off and Williamson will know whether the gamble he took when he purchased her as a yearling has paid off.

Williamson is what’s known in the industry as a “pinhooker” – someone who buys to sell on for a profit.

The term is said to have come from the tobacco fields of Kentucky and describes a speculator who would buy up a farmer’s young plants and later identify them with a pinned note at market.

If this conjures up images of shadowy figures lurking at the racetrack, hats pulled down low over brows, the reality is more professionalized. Pinhookers can add value by overseeing the breaking and training of a young horse with a view to reselling it as race-ready two-year-old.

Nevertheless, buying and selling horses is still a risky venture. In an industry where the vast majority of horses will see their value peak before they even set foot on a racetrack, profit lies in this imponderable space between potential and performance. Yet pinhooking is still a job that exists on the margins.

“It’s all very well buying a nice, expensive horse but you’ve got to see some profit in there as well,” says Malcolm Bastard, a former jockey who now makes his living pinhooking.

“I was at the end of my career and I had a friend who had pinhooked a couple of horses and done pretty good, so I thought I’d have a go.”

A quarter of a century later he has a staff of 30 based at his farm in Wiltshire, where the horses he buys as yearlings in the autumn sales are broken in and pre-trained, ready to gallop at the racetrack.

One of the largest consignors, Bastard has brought 11 horses to Newmarket to sell.

“You’re looking for a strong horse that can take a bit of training and perform well on the track in the spring,” he explains.

In simple terms, if the horse can run fast and move well, the upside can be substantial. But spotting a horse with the right qualities takes skill, experience and luck.

“It’s up and down with horses,” concedes Bastard. “You have to take the rough with the smooth and hope the good years will carry you through the ones where you don’t make any money.”

Most of the horses at these sales began their journey with one of the UK’s 300 full-time stud farms or 3,500 part-time breeders. The breeding industry is the first link in a $5.8 billion chain that makes up the British racing industry, along with owners, racegoers and gamblers.

In the UK, around 4,000 foals are produced annually, most of which will be sold through public auctions like this one. A smaller number are sold privately, while the larger breeding operations such as Juddmonte in the UK and Coolmore in Ireland tend to keep theirs in-house.

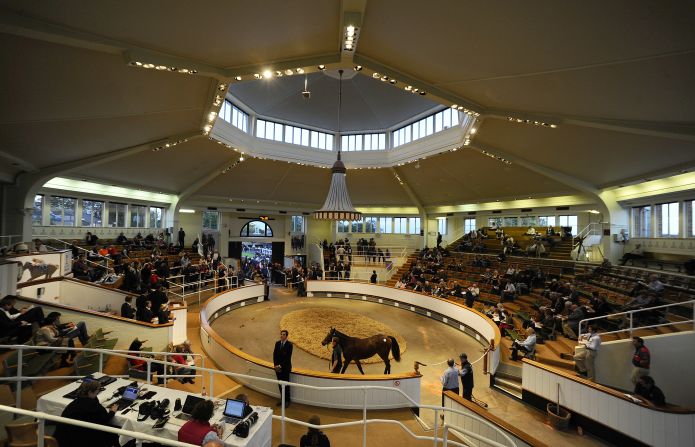

As the UK’s largest bloodstock auctioneer, Tattersalls can expect to see a large proportion of these 4,000 pass through its iconic domed sales ring at some point in their careers.

The breeding industry is slowly emerging from the effects of the global economic downturn. Following a decade of growth in the 1990s, the sector found itself at the sharp end of major falls in the value of bloodstock sales when the financial crisis hit in 2008.

Total revenue from Britain’s two main auction houses, Tattersalls and Doncaster, slumped by a combined $150 million from their peak of $509 million in 2007 to $358 million in 2008, according to Deloitte’s Economic Impact of British Racing 2013 report.

Since 2012, however, fortunes have been looking up, exemplified by the sale of Hydrogen, another Galileo foal, by Tattersalls for $4.4 million – the highest price paid for a yearling in the world that year.

But hovering over every blockbuster sale like Hydrogen is the ghost of The Green Monkey – a cautionary tale for any buyer looking to open their wallets on an unraced prospect.

The Green Monkey was pinhooked as a yearling and sent to Florida’s Fasig Tipton Calder Sale in 2006. Impeccably bred (his grandsire was Storm Cat, giving him a direct link to both Northern Dancer and Secretariat in his pedigree), he fetched a world record price of $16 million.

Unfortunately, from the moment he set foot on the track, The Green Monkey was a flop and was retired after failing to break his maiden (win for the first time) in three starts. Although he has redeemed himself somewhat in his career as a stallion, with a stud fee of $5,000, it proves that there is no such thing as zero risk when it comes to buying and selling horses.

Newmarket-based trainer Roger Varian is among those who are skeptical that the risks can ever truly be mitigated.

“If anything I think it’s more risk because the horse has had to go through a degree of pressure training already to breeze sufficiently quickly to make it commercial,” he says.

“When you buy a yearling it’s a blank canvas and you can shape or mold the horse to suit you. When you buy a horse from a breeze-up you have to be a little bit cautious that you aren’t getting a horse who has done too much, too soon.”

George says the success of such sales for Tattersalls depends on how well the horses bought do in future.

“It’s key that this sale continues to produce winners – and high class winners at that – because that’s what keeps buyers coming back year after year,” he says.

“Everybody needs to be happy, not just the vendors.”

As the auction begins, a cacophony of guineas, whinnies and gavels, it’s clear there will be some happy vendors at the end of the day. As the oldest bloodstock auctioneers in Europe, dating back to 1766, Tattersalls maintains its prerogative to trade in guineas, an archaic currency that was last in widespread use in England in 1816.

Equivalent to £1.05 ($1.77) in today’s money, the five-pence handily denotes the auctioneer’s commission: 5% from the vendor or consignor. Soon it is Lot 99’s turn to go through the sales ring.

Ears pricked and treading daintily, she soon attracts attention from bidders. When the hammer falls her price has reached 200,000 guineas ($354,000).

It’s a very good price, but she is far from the most expensive two-year-old sold that day: a colt by War Front fetches 1.15 million guineas ($2,035,500) – a new European record and the highest price anywhere in the world this year.

“It’s brilliant, I can’t believe it,” consignor Willie Browne said after the sale, in which 93 of the 128 lots were claimed for a two-day total of 10,489,000 guineas – an increase of 14% on last year.

“I knew he was popular – he did a great breeze, he ticked all the right boxes, all the ingredients were there for a big price. And, of course, he is by the right stallion,” Browne added.

“He was led out in the U.S. unsold at $240,000 as a yearling and I’d thought I’d go and get him privately for $200,000. In the end I had to pay $250,000, but he was worth it.”

See also: Thoroughbred therapy on Cape Town coast