Explore the City of Tomorrow, Saturday, July 26 at 2 p.m. ET on CNN.

Story highlights

Unfulfilled promises of superwired smart cities spark a dubious backlash

Expert: Stifling U.S. bureaucracy and fear of risk stand in the way

Some U.S. cities are embedding data sensors in energy grids, buildings, traffic hubs

Smart tech could save billions of dollars and reduce energy use, traffic jams, carbon pollution

Years ago, experts told the world that the Internet would radically change our cities. A lot of us are still waiting.

How cool, they said. Cities will be able to use the language of data to virtually talk to us, sharing information so communities can become superefficient, saving untold billions of dollars. Traffic management would untangle our commutes. Carbon emissions would plummet.

Life, they said, would get a little easier.

Well, some of this stuff is actually happening in places around the world. But in many other cities, businesses and governments have been … moving … kind of … slow.

So. What’s the hold up? Where’s my talking city?

Apparently all those predictions a few years ago resulted in a dubious backlash, says Constantine Kontokosta, department director at New York’s Center for Urban Science and Progress.

Experts “made a lot of promises about what this technology, just for technology’s sake, could do.” Now, Kontokosta says the emphasis is on using smart city technology to help people make better decisions for themselves.

During the past few years, a handful of so-called smart cities have been built from the ground up, in places such as the United Arab Emirates, South Korea and Japan.

You’ve got to wonder what they’ll teach us about how to bring smarter technology to the places we live, play and work. How might that technology grow in the United States? What should American city dwellers expect in the next five years?

Let’s take a look at the smart coastal city of Songdo, near Incheon, South Korea. Price tag: roughly $35 billion.

Although it’s not due to be completed until 2017, tens of thousands of people live there already, according to developers. Eventually the city plans to be home to 65,000 residents and a workplace for 300,000 commuters. Sensors distributed throughout buildings and roads monitor and regulate energy consumption and traffic flow. Sensors also tell commuters when their bus is coming. Inside homes, a trash disposal system sucks household garbage from kitchens through long tunnels to waste processing centers.

Near Porto, Portugal, construction of a smart city called PlanIT Valley has been delayed by the nation’s economic troubles in 2011. Developers reportedly are about to begin building the first phase, which would house about 7,000. PlanIT Valley has what planners call an “operating system,” which includes millions of sensors that send data in real time to a central computer that uses the information to keep the city working at peak environmental efficiency.

Theoretically, buildings would be able to sense if they’re on fire, alert firefighters and coordinate traffic flow to help first responders arrive a the scene as soon as possible.

In the United Arab Emirates, the solar powered desert berg of Masdar City reportedly is about to break ground on its first neighborhood of 500 smart private homes. Masdar has boasted environmentally sustainable educational and business districts for several years, and planners promise its homes will include technology that make them “super sustainable.”

Japanese developers recently opened the town of Fujisawa SST, about an hour west of Tokyo by train. This solar powered city, built by Panasonic, is shaped like a leaf and built in three layers – one on the surface and two underground. Residents started moving there in March, numbering about 30 families so far. The city manages its energy needs in real time by coordinating data from sensors linked to home appliances. By the time it’s completed in 2018, Fujisawa SST is expected to include 1,000 households. It aims to provide a global showcase on how to generate renewable energy while reducing carbon dioxide emissions and cutting water use.

“It’s important to remember that Fujisawa SST is not an experiment, but a project to create a smart sustainable town that continues to grow and develop, with the residents at the core,” says Panasonic spokesman James Bell.

The project website announces: “We now release our Fujisawa model to the world!”

Confidence is high, but so are the stakes. These smart cities have a lot to prove.

For one, they’ve got to show that their models can solve energy and efficiency problems comprehensively in places where people live and work. They also have to demonstrate their successes are not isolated examples. In other words, their solutions have to be replicable in other locations.

“The technology is the easy part, quite frankly,” says infrastructure expert Robert Puentes of the Washington think tank, the Brookings Institution. “We know that these things work. It’s how you get it done in existing complex environments that’s going to be the hard part.”

Infrastructure has gotten smarter in existing cities across Western Asia, China and Africa. In Europe, it’s especially evident in Barcelona, Spain; Copenhagen, Denmark; Vienna, Austria; Manchester, England; and Paris.

In the United States, experts say smart cities built from scratch will be unlikely. Retrofitting smart tech into existing city infrastructure has been going on for a while now. The built-from-scratch cities might have lessons to offer.

“Masdar is developing water conservation solutions with lessons to be learned in places like Las Vegas and Phoenix, cities which are still growing here in the United States,” Puentes says.

Innovation districts

Experts point to U.S. cities leading the way, such as Chicago, New York, San Francisco, Philadelphia, Boston and Seattle.

Some communitieshave established special innovation districts that are outfitted with smart technology and a lot of broadband Internet. The idea is to attract businesses that want smart tech efficiency to move to those districts. From those seeds, planners hope a smart tech wave will spread citywide.

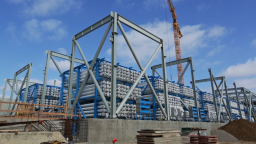

Now under construction on Manhattan’s West Side: Hudson Yards, an ambitious 28-acre neighborhood of skyscrapers filled with offices, retail and residential space. By the time it’s completed in 2018, Hudson Yards is expected to be highly wired up.

How’s the air quality? They’ll track it. Energy use? Check. Movement of garbage and recyclables? They plan data for that. There will be data tracking movement of people on the property. If tenants want to, they can use the building’s smartphone app to track their personal health stats.

“We have a lot of experiments going on around the U.S. right now,” says Puentes. “It’s getting those routinized that’s going to be a big challenge. That will be a big problem throughout the United States. There’s really nobody that’s doing it all completely perfect.”

The key is looking at the data as a whole, so community leaders can use it to see the big picture and make changes that will yield big benefits like reducing carbon emissions or saving money.

But progress has been slow. Experts blame the most recent recession, fear of risk and bureaucratic inertia. Also, differing business cultures add another layer to the challenge.

“In many cases the real estate industry is one that’s very slow to change,” says Kontokosta. “This is a rather dramatic paradigm shift for how the real estate industry and how planners will conduct their business. So I think it’s going to take a little bit of time, but we’re starting to see momentum building.”

Shake it up

One suggestion, say experts: shake up the bureaucracy.

“Historically cities have operated in silos along different agencies,” says Kontokosta. “But as we’re getting into this ability to measure and monitor all kinds of data, cities really need to have much tighter cohesion – much more coordination – across different branches.”

“We’ve got to reform government in many ways and formalize collaboration between different city agencies,” says Puentes. Problem-solving mayors are appointing business-savvy data chiefs who coordinate several departments. They’re armed with mandates to make things happen.

And it’s not just about sensors inside buildings and bridges. In Louisville, Kentucky, smart sensors embedded in asthma inhalers were used in a medical study that pinpointed locations of asthma attack clusters and then investigated whether the locations contributed to the attacks.

“Where I see the best use of all of this smart technology is ways to improve quality of life,” Kontokosta says. “Including understanding the connection between poverty and health and the built environment.”

Within the next five years, the U.S. can expect to see more smart tech linked to transportation. Why? Government officials with tight budgets will want to increase efficiency. “Once states realize there’s not a lot of money coming for new construction, they’re going to have to figure out new ways to solve problems like traffic congestion,” Puentes says.

Right now, the biggest challenge surrounding the installation of large-scale smart tech is cost.

The solution, Puentes says, includes finding the right mix of public and private networks that can finance retrofitting the nation’s big cities. “If we can get those business models done right,” he says, “then there’s no stopping this.”

What smart city tech are you seeing in your community? Let us know about it in the comments section below.