Editor’s Note: This is the third in a series on the legacies of World War I. It will appear on CNN.com/Opinion in the weeks leading up to the 100-year anniversary of the war’s outbreak in August. Ruth Ben-Ghiat is guest editor for the series. Thomas Schlich is Professor in History of Medicine at the Department of Social Studies of Medicine at McGill University. The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of the author.

Story highlights

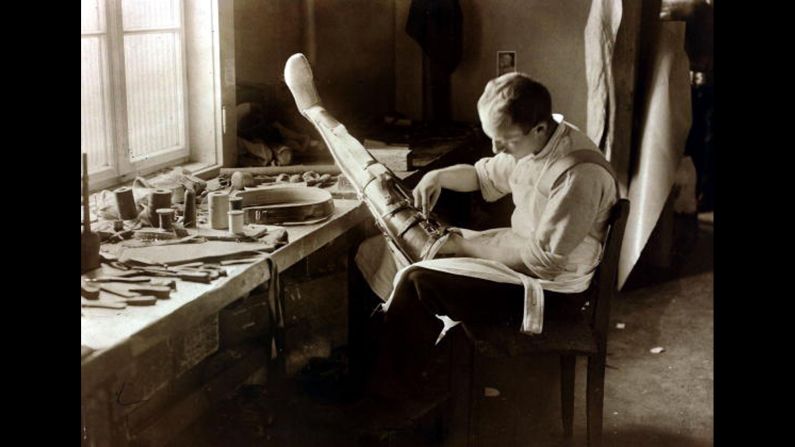

Thomas Schlich: The mutilation of soldiers in WWI led to revolution in prosthetic limbs

He says engineers create limbs that would let vast crop of amputees into labor force

Germany was at fore, creating prostheses that literally linked the man to his work station

Schlich: Some see it as a kind of 'human evolution;' it set stage for advanced bionics

World War I slaughtered and mutilated soldiers on a scale the world had never seen. It’s little wonder that its vast numbers of returning crippled veterans led to major gains in the technology of prosthetic limbs.

Virtually every device produced today to replace lost body function of soldiers returning from our modern wars – as well as accident victims, or victims of criminal acts, such as the Boston Marathon bombings – has its roots in the technological advances that emerged from World War I.

The war, which began nearly 100 years ago, produced its own crop of bionic men. In previous wars, severely injured soldiers often succumbed to gangrene and infection. Thanks to better surgery, many now survived. On the German side alone, there were 2 million casualties, 64 percent of them with injured limbs. Some 67,000 were amputees. Over 4,000 amputations were performed on U.S. service personnel according to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

How a century-old war affects you

In all nations involved in the war an emerging generation of so-called “war cripples,” as they were referred to in Germany, loomed ominously over the pension and welfare system, and many government bureaucrats, military leaders and civilians worried about their long-term fate.

One solution was returning mutilated soldiers to the workforce. Various prostheses were designed to make that possible, pushing prosthesis manufacturing in many countries from a cottage industry towards modern mass production.

In the United States the Artificial Limb Laboratory was established in 1917 at the Walter Reed General Hospital, in conjunction with the Army Medical School, with the goal to give every amputee soldier a “modern limb,” enabling them to pass as able-bodied citizens in the workplace. While the United States remained the largest producer of artificial limbs worldwide, Germany’s prosthetic developments incorporated a particular quest for efficiency.

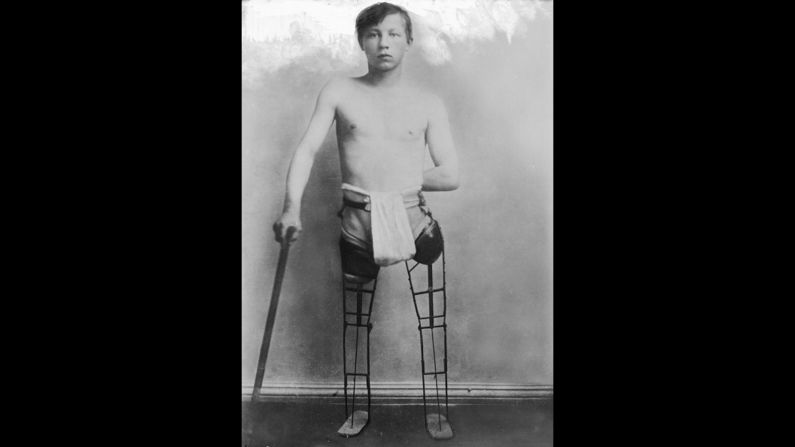

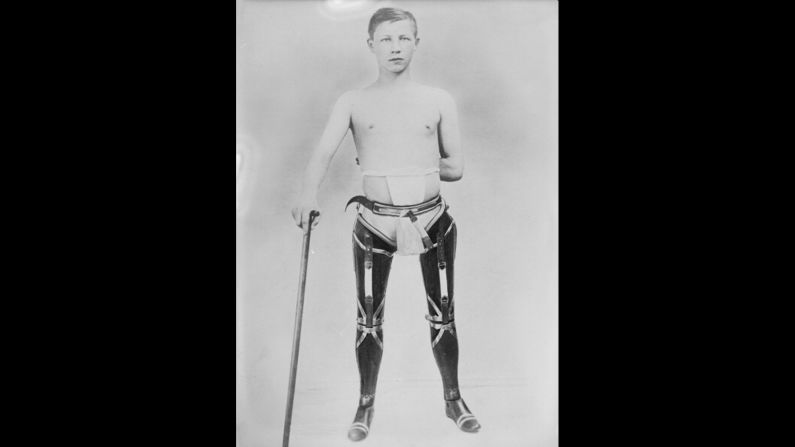

German orthopedists, engineers and scientists invented more than 300 new kinds of arms and legs and other prosthetic devices to help. Artificial legs made of wood or metal, sometimes relatively rudimentary, and often recreating the knee-joint in some way, enabled leg-amputees to stand and move around unaided.

War's legacy

WAR’S LASTING LEGACY

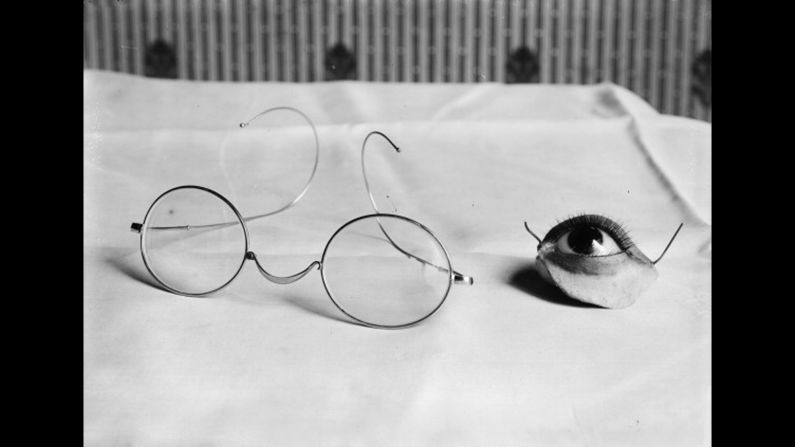

Glass eyes and a variety of facial prostheses allowed those with defacing injuries to appear in public. For example, a galvanized and painted copper plate could fill in the missing eye socket and neighboring maxillary bone.

A lost arm or hand was particularly difficult to replace. In the United States engineers had designed a mechanical arm for that purpose that came into wide use after the war. The so-called Carnes arm was not optimal for mechanical work, but it imitated the natural limb and was relatively easy to mass produce cheaply. It became a huge business success.

How World War I gave us ‘cooties’

In Berlin, the Test Center for Replacement Limbs evaluated prosthetic technologies, such as the Carnes arm. Positioned at the confluence of medicine, engineering and the new science of ergonomics, the test center offers a particularly striking example of the setting that made modern prosthetics possible.

The center’s head, the engineer and professor Georg Schlesinger, was an adherent of Frederick Taylor’s “scientific management” – an approach that applied scientific methods to optimize work flows and labor productivity. His idea of a proper prosthesis was something functional and efficient, an exchangeable and mass producible replacement device that would fit with the human body.

While earlier prostheses often tried to replicate body appearance, or to follow the inner structural plan of the original appendage – its shape, muscles, sinews– Schlesinger saw no need to do that. He reasoned that airplanes could fly without imitating birds’ wings, so why did prosthetics have to mimic arms and legs?

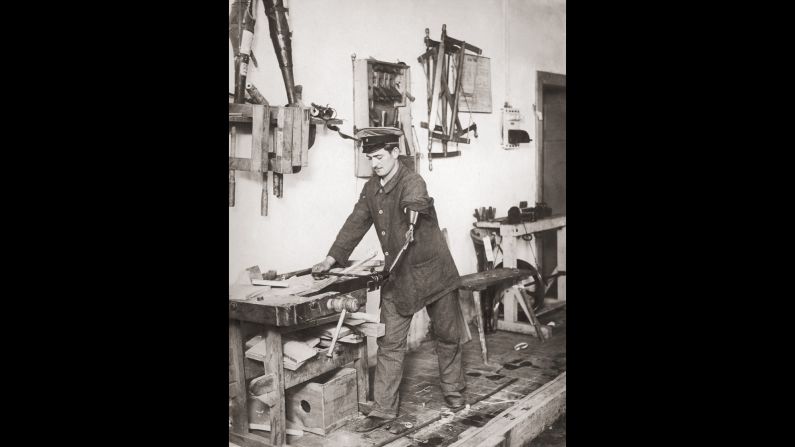

The Siemens-Schuckert-Works Universal Arm, invented in 1916, was a remarkable example of functional efficiency. It was basically a tool-holder with interchangeable parts. Its “hands” ranged from a simple hammer to cutlery with elongated handles to inserts whose ends could be attached to machines. It could serve the carpenter, farmer, draughtsman, locksmith, lathe-turner, cabinet-maker or tinsmith.

Many of these prostheses literally merged man and machine, leaving the disabled man firmly attached to his work station. An amputee veteran would arrive at his work place in the factory, hook up the remaining part of his limb to the prosthesis, which in turn would be linked to one of the industrial machines in the factory. He would work for hours like this as a link in a functional kinetic chain.

The image of men tied to their work resonates unsettlingly with Karl Marx’s prediction that the urban proletariat would one day become a mere “appendage of the machine.” It’s an example of how military and industrial conceptions of the body were extended to dehumanize the body itself.

Some visionaries, of course, embraced prosthetics as a means for human transformation, as if the body were a malleable object that could be dignified and enhanced by technology.

And some thinkers go even further and interpret technological enhancement as a next step in human evolution.

Reality might not be so far behind: In 2008 runner Oscar Pistorius, a double-leg amputee, sought to compete in the Bejing Olympics, but his running blades, made of carbon fiber and modeled after a cheetah’s leg, were seen by some as an unfair advantage. Four years later in London, he did compete in the Olympics, embodying a development that had its origins 100 years earlier, in World War I.

Read CNNOpinion’s new Flipboard magazine