Story highlights

Bodies, wreckage are scattered over eastern Ukraine countryside

Some people bound for Malaysia died in vacation clothes, reporter says

Bodies are starting to decompose in the heat

Heavily armed pro-Russia militants control the crash site

The sense that a deadly tragedy could get worse hangs over the crash site of Malaysia Airlines Flight 17.

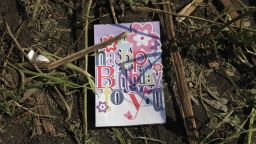

Scattered bodies, ripped-apart suitcases and charred books testify that 298 people died Thursday when the airplane fell from 30,000 feet to the grassy fields of an almost-lawless section of eastern Ukraine.

More than 24 hours after the crash, the bodies lay there untouched, with nobody able to say who’s in charge and whether the dead would ever be treated with dignity.

“It basically looks like the biggest crime scene in the world right now, guarded by a bunch of guys in uniform with heavy firepower who are quite inhospitable,” Michael Bociurkiw, spokesman for the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe team, told CNN’s Christiane Amanpour.

The bodies are starting to decompose in the Ukraine summer heat, the stink mixing with the charred odor coming from the wreckage.

Surrealistic signs of death carpet the countryside.

Some on the Malaysia-bound plane were dressed in sandals, shorts and other clothes people wear on a tropical vacation, said Noah Sneider, a freelance journalist who visited the crash site.

At one spot he noticed a printout of the top 10 tourist tips for people visiting Bali.

Some passengers, he said, died strapped into their seats wearing headphones, as if listening to music or watching an onboard movie.

Emergency workers say they’ve found more than 170 bodies across a wide area, some caught up in large pieces of the aircraft, others simply lying where they fell. Some bodies are mangled so much it’s impossible to say if they’re man or woman, others show no marks or injury.

In the darkness, it’s not hard to stumble across a body.

The region is controlled by pro-Russian militants, who gave a rude reception Friday to monitors on the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe team. They were in the region to observe the war and aren’t air crash investigators.

“We asked for the commander, the leader,” Bociurkiw told Amanpour. “No one showed up.

“There was one gentleman there in a uniform, heavily armed, and apparently somewhat intoxicated who wasn’t very hospitable or helpful at all. In fact in the end he kind of rushed all of them away, including the journalists.”

Bociurkiw said the team spent only 75 minutes at the crash site and examined only a 200-meter strip before being chased away. In the distance, he heard explosions, a familiar sound in this region ripped apart by war.

“The perimeter is not secure whatsoever,” Bociurkiw said. “They seemed to have put some tape up where we were standing, but otherwise it’s very easy for anyone, really, to walk in there and tamper with evidence or debris. So a lot of work needs to be done. A lot of professional work, very, very quickly.”

In the United States or other Western nations, law enforcement would have put the crash site off limits to the morbidly curious right away. In east Ukraine, reporters walked right up to pieces of wreckage to do stand-up reports.

A small crew of emergency workers from the Ukraine government arrived and began working on the scene, but they need more people and resources to properly handle a crash that killed 298 people. They’re obviously working with the permission of the militants. At night the groups mingled, seemingly without hostility, and even shared tents.

Meanwhile, the world is watching. The clock is ticking.

“It is cool right now,” Bociurkiw said, “but if it’s a warm day tomorrow, it will continue to turn into quite a messy situation.”

Jason Hanna of CNN contributed to this report.